Introduction

In every social or professional circle, there’s often that one person who seems to have it all together—the “strong friend.” They are the problem-solvers, the dependable ones, always ready to lend support, give advice, or shoulder burdens. On the surface, these individuals exude strength, confidence, and competence. Yet behind their composed exterior, many of them silently struggle with depression, anxiety, and burnout.

The “strong friend” is frequently the high-achiever: driven, successful, and admired. But beneath their accomplishments lies an internal pressure cooker of perfectionism, self-doubt, and emotional neglect.

Read More- Main Character Syndrome

The High-Achiever’s Dilemma

High-achievers are often characterized by ambition, discipline, and an unrelenting drive for excellence. While these traits are frequently celebrated in both personal and professional contexts, they come with a psychological cost. Many high-achievers struggle with maladaptive perfectionism, which is the pursuit of flawlessness paired with overly critical self-evaluations (Flett & Hewitt, 2002). Unlike adaptive perfectionism, which can be motivating and goal-oriented, maladaptive perfectionism is associated with chronic dissatisfaction, stress, and an increased risk of depression.

A 2018 meta-analysis published in Psychological Bulletin examined over 40,000 individuals and found a significant rise in perfectionism over the past three decades, especially among younger generations (Curran & Hill, 2018). The researchers noted that socially prescribed perfectionism—where individuals believe others expect them to be perfect—is most strongly linked to depression and suicidal ideation.

This “always-on” mentality often leads high-achievers to ignore signs of emotional fatigue, pushing themselves to meet increasingly unattainable standards. Their self-worth becomes inextricably tied to achievement, creating a cycle in which success provides temporary relief but never long-term fulfillment.

The Burden of People-Pleasing

Beneath the high-achiever’s drive is often a deeply ingrained need for external validation. Many strong friends are chronic people-pleasers, individuals who prioritize the needs and expectations of others over their own well-being. While altruism and empathy are admirable traits, when rooted in fear of rejection or a desire for approval, they can be psychologically damaging.

People-pleasing behavior frequently stems from childhood experiences where love and acceptance were conditional on performance or compliance (Braiker, 2001). Over time, this pattern solidifies into a belief system: “If I do not meet others’ expectations, I am unworthy of love.”

This results in self-neglect, where the individual’s own needs are consistently subordinated to those of others. The cumulative effect is emotional exhaustion, burnout, and a diminished sense of self. A study published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology found that people-pleasers are more likely to experience workplace burnout and lower life satisfaction due to constant emotional labor and boundary violations (Molinsky, 2013).

The Inner Critic and Impostor Syndrome

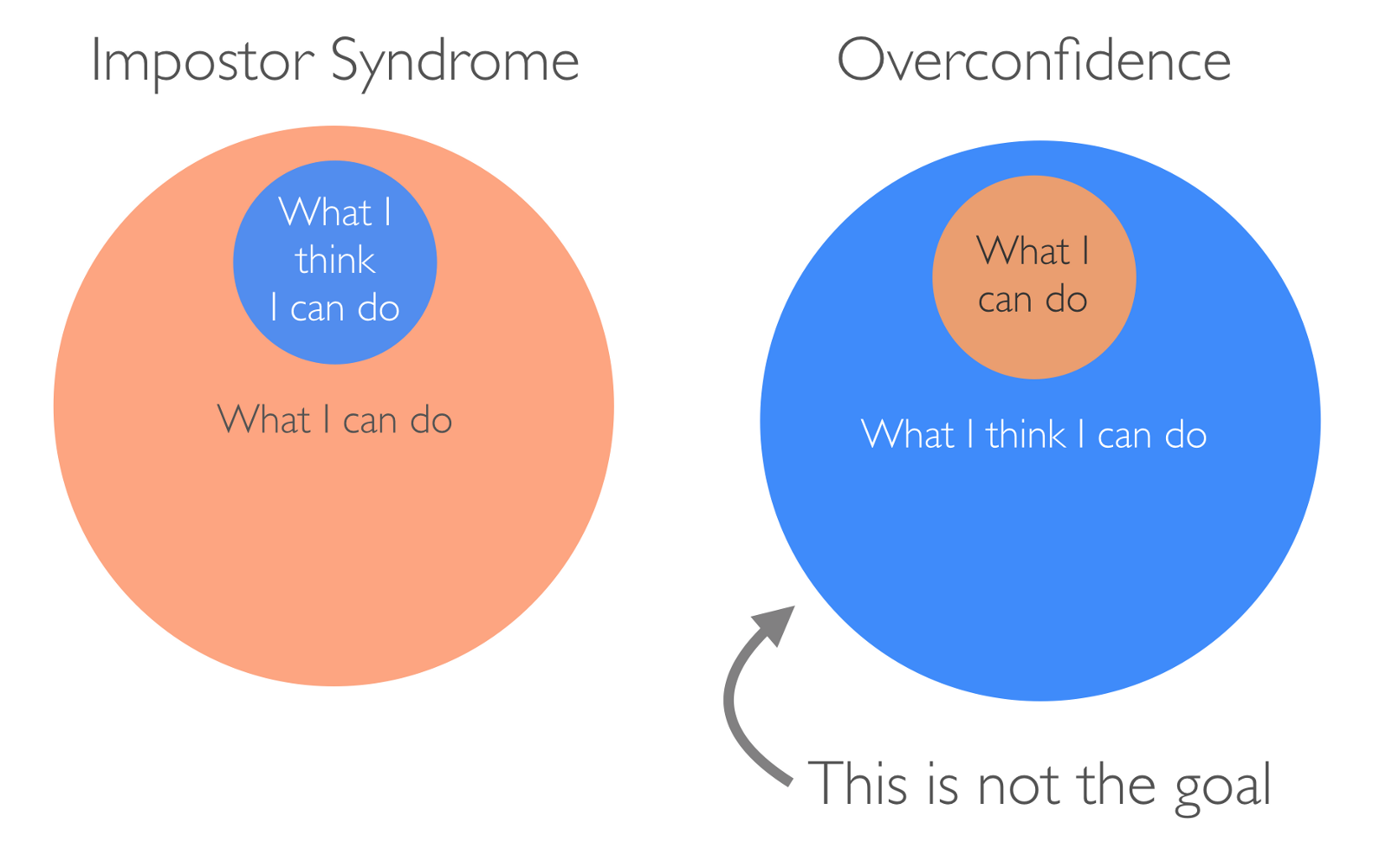

Even when high-achievers reach the pinnacle of success, many are plagued by a persistent belief that they don’t truly deserve their accomplishments. This is known as impostor syndrome, a psychological pattern characterized by chronic self-doubt and a fear of being exposed as a fraud (Clance & Imes, 1978). Despite objective evidence of competence, those with impostor syndrome attribute their achievements to luck, timing, or deception.

This condition is often compounded by an inner critic, a harsh internal voice that scrutinizes every action and minimizes every success. The inner critic tells the high-achiever that their work is never good enough, that rest is laziness, and that vulnerability is weakness. These internalized beliefs reinforce shame and silence, making it even harder for the individual to seek support.

Impostor syndrome is particularly prevalent among high-functioning individuals in competitive environments. According to research published in the International Journal of Behavioral Science, up to 70% of people experience impostor feelings at some point in their lives, with high-achieving women and minorities reporting the highest rates (Gravois, 2007).

Societal Expectations and the ‘Strong Friend’ Persona

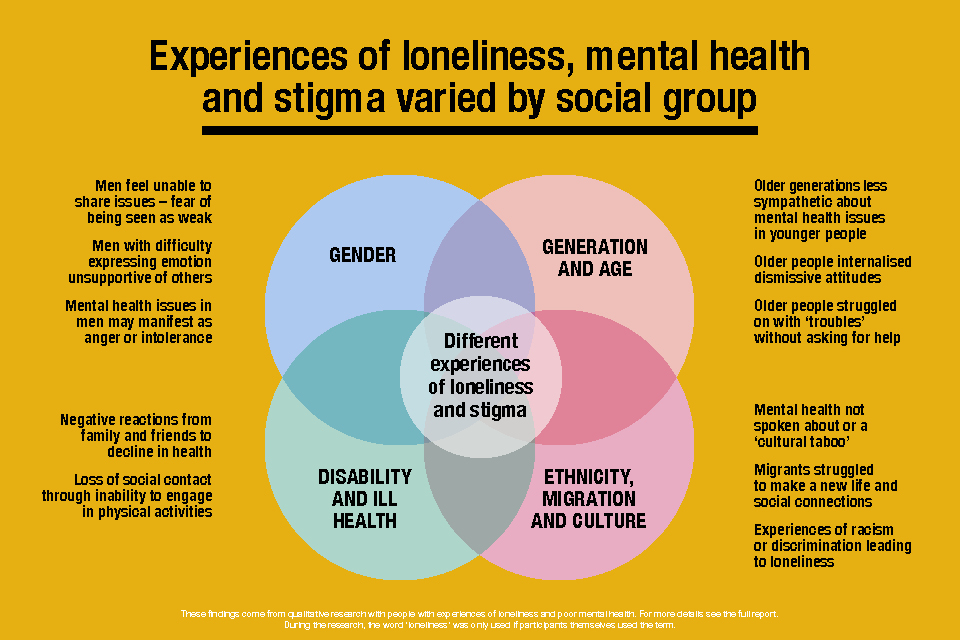

The “strong friend” archetype is not only internally driven—it is reinforced by cultural and societal narratives. In Western societies especially, there is a strong emphasis on individualism, resilience, and self-reliance. These values, while empowering in moderation, can stigmatize vulnerability and emotional openness.

The strong friend is often cast in the role of the caregiver, the mentor, the reliable leader. Their emotional needs are overlooked, and their strength becomes both a reputation and a prison. When they struggle, they are often met with disbelief or discomfort: “But you’re always so put together,” or “You’re the strong one—we look up to you.” These responses, though well-intentioned, invalidate the person’s pain and reinforce their sense of isolation.

In communities of color, religious groups, and immigrant families, the pressure to be the “pillar of strength” is often amplified by intergenerational trauma, systemic marginalization, and the burden of representation (Hooks, 2004). Mental health is still a taboo in many of these settings, further disincentivizing open conversation.

Strategies for Support

Overcoming the hidden depression of the strong friend requires a collective shift in how we view strength, success, and vulnerability. Below are evidence-based strategies to support high-achievers in navigating their mental health:

1. Encouraging Open Conversations

Creating safe, non-judgmental spaces for mental health dialogue is essential. Open-ended questions like, “How are you really feeling?” can prompt deeper reflection and foster connection. Initiatives like Mental Health First Aid and peer support groups are effective in reducing stigma and increasing awareness (Kitchener & Jorm, 2002).

2. Promoting Self-Compassion

High-achievers often show compassion to others but struggle to extend it to themselves. Dr. Kristin Neff’s research on self-compassion shows that individuals who practice kindness toward themselves experience lower levels of anxiety and depression and are more resilient in the face of setbacks (Neff, 2003).

Self-compassion involves treating oneself with the same understanding one would offer a friend, acknowledging that imperfection is part of the human experience.

3. Setting Boundaries

Many high-achievers lack the skill—or permission—to say no. Boundary-setting is crucial for preserving mental energy and preventing burnout. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) techniques can be helpful in identifying people-pleasing behaviors and challenging the irrational beliefs behind them (Beck, 2011).

Role-playing assertive communication, practicing delayed responses, and reevaluating priorities are practical strategies to implement healthier boundaries.

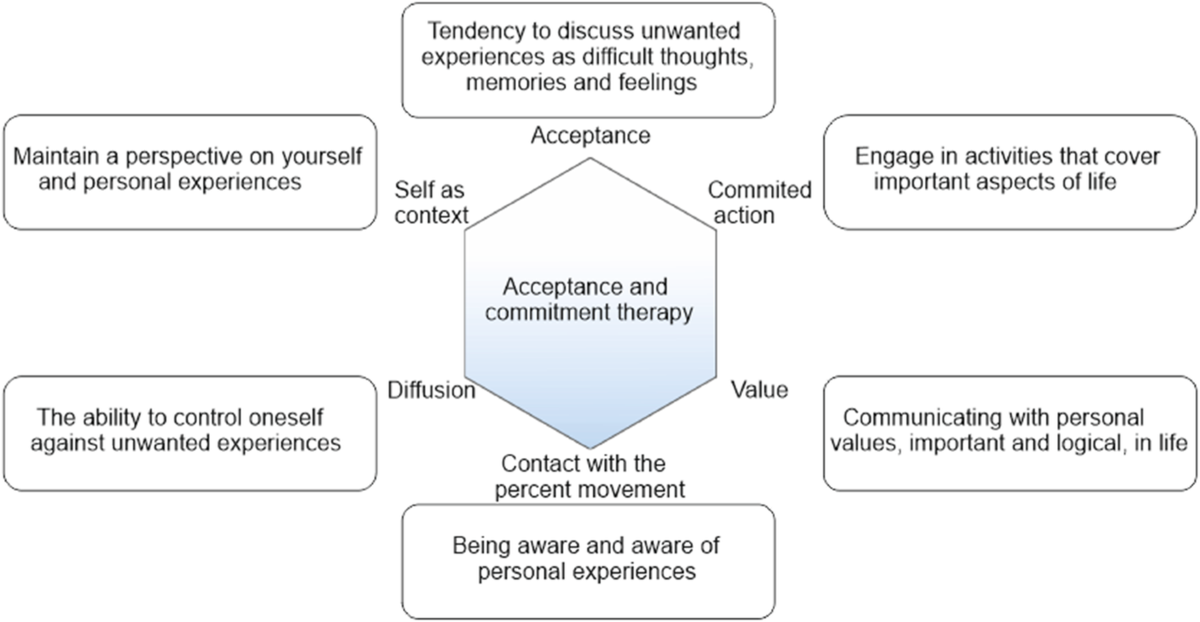

4. Seeking Professional Help

Therapy should not be seen as a last resort but as a proactive step toward emotional wellness. There is growing recognition of the effectiveness of therapy for high-functioning individuals. Approaches such as schema therapy, CBT, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) are particularly effective for addressing perfectionism, impostor syndrome, and chronic stress (Young et al., 2003).

Online platforms like BetterHelp and Talkspace have also expanded access to therapy, particularly for those who may feel uncomfortable with traditional settings.

Conclusion

The “strong friend” archetype is both admired and misunderstood. While these individuals often lead, uplift, and inspire, they may also endure silent battles with mental health that go unnoticed and unaddressed. The cost of unrelenting strength is emotional isolation, and the price of perfectionism is chronic dissatisfaction.

To truly support our strong friends, we must shift the narrative around mental health. Strength should not be measured by stoicism or self-sacrifice, but by the courage to be authentic, to rest, and to ask for help. By fostering open conversations, practicing self-compassion, setting boundaries, and embracing vulnerability, we can begin to dismantle the walls that keep high-achievers isolated—and help them lead not just successful lives, but fulfilling ones.

References

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Braiker, H. B. (2001). The Disease to Please: Curing the People-Pleasing Syndrome. McGraw-Hill.

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241–247.

Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2018). Perfectionism Is Increasing Over Time: A Meta-Analysis of Birth Cohort Differences From 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 144(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000138

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment. American Psychological Association.

Gravois, J. (2007). You’re Not Fooling Anyone. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(11), A1.

Hooks, B. (2004). We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity. Routledge.

Kitchener, B. A., & Jorm, A. F. (2002). Mental health first aid training for the public: Evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry, 2(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-2-10

Molinsky, A. (2013). The Psychological Price of People-Pleasing. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. Guilford Press.

Psychology Today. (n.d.). Impostor Syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, June 12). The ‘Strong Friend’ Persona and 4 Important Strategies For Support. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/strong-friend-persona/