Introduction

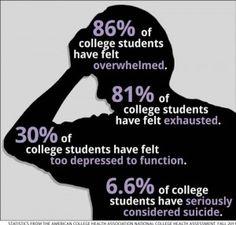

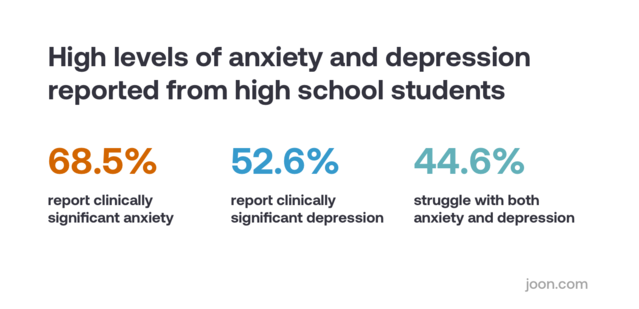

Youth mental health has become one of the most pressing concerns of the 21st century. Children and adolescents face increasing academic demands, social pressures, and exposure to global crises through digital media. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021), one in seven adolescents (ages 10–19) experiences a mental disorder, with depression, anxiety, and behavioral conditions among the leading causes of illness and disability. Early intervention is critical, as untreated mental health challenges in youth often persist into adulthood, affecting educational attainment, career success, and overall well-being.

Parents and teachers—two of the most influential forces in young people’s lives—are uniquely positioned to identify early warning signs and provide supportive interventions.

Read More: Suicide Awareness

Understanding Youth Mental Health

Mental health in youth is not merely the absence of mental illness; it includes the presence of positive functioning, resilience, and emotional regulation (Keyes, 2002). Good mental health allows students to build strong relationships, manage stress, and thrive academically and socially.

Common Mental Health Challenges in Students

- Anxiety disorders: Generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and test anxiety are widespread in school-aged populations (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009).

- Depression: Adolescents experiencing depression often show irritability, withdrawal, and declining academic performance (Thapar et al., 2012).

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, ADHD affects learning and classroom dynamics (Barkley, 2015).

- Eating disorders: Increasingly common among adolescents, particularly due to social media influences (Neumark-Sztainer, 2019).

- Self-harm and suicidality: Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among 15–19-year-olds globally (WHO, 2021).

Risk and Protective Factors

Risk Factors

Some risk factors includes:

- Academic pressure and high-stakes testing

- Bullying and peer victimization

- Family conflict or neglect

- Socioeconomic disadvantage

- Excessive social media use

- Exposure to trauma

Protective Factors

- Supportive relationships with parents and teachers

- Positive school climate

- Access to counseling and health services

- Strong coping skills and resilience training

- Engagement in extracurricular activities

Recognizing these factors allows educators and caregivers to intervene early, reducing the likelihood of escalation into more severe mental health problems.

Eight Effective Early Intervention Strategies

Some early intervention strategies include:

1. Create Open Channels for Communication

Encouraging students to express their feelings is the foundation of early intervention. Parents and teachers can model emotional literacy by naming their own emotions and inviting open dialogue. Research shows that open communication within families is associated with lower rates of adolescent depression and anxiety (Ackard, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Perry, 2006).

Practical tip: Daily check-ins—asking students “What was the best and hardest part of your day?”—normalize emotional sharing.

2. Recognize Early Warning Signs

Early signs of mental health challenges often manifest as subtle changes in behavior, such as withdrawal from friends, declining grades, irritability, or frequent physical complaints (Kern et al., 2017). Teachers, who observe students daily, are especially well-situated to notice these changes.

Practical tip: Keep observational logs of student behavior and communicate concerns with parents and school counselors.

3. Build Emotional Resilience Skills

Resilience training equips students to cope with stress and setbacks. Programs that teach mindfulness, problem-solving, and self-regulation have been shown to reduce anxiety and improve well-being in children (Zenner, Herrnleben-Kurz, & Walach, 2014).

Practical tip: Incorporate brief mindfulness exercises or journaling activities at the start of class.

4. Foster Strong Parent–Teacher Partnerships

Collaboration between parents and educators ensures consistent support across home and school environments. Regular communication builds trust and enables early, coordinated responses to concerns (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001).

Practical tip: Hold quarterly “well-being conferences” in addition to academic reviews.

5. Normalize Mental Health Conversations

Stigma remains one of the biggest barriers to seeking help. By treating mental health discussions as routine and important—like discussions of physical health—adults reduce shame and encourage help-seeking behaviors (Corrigan, Druss, & Perlick, 2014).

Practical tip: Teachers can weave mental health literacy into curriculum through literature, history, or health classes. Parents can discuss their own coping strategies at home.

6. Encourage Healthy Lifestyle Habits

Sleep, nutrition, and exercise are strongly linked to mental health. Students who get regular physical activity and sufficient sleep report lower stress and higher academic performance (Dewald, Meijer, Oort, Kerkhof, & Bögels, 2010).

Practical tip: Schools can incorporate movement breaks, while parents can enforce consistent sleep routines.

7. Provide Access to School-Based Mental Health Resources

On-campus counselors, social workers, and peer-support programs offer immediate support. Research shows that students are more likely to seek help when services are accessible within the school setting (Reinke, Stormont, Herman, Puri, & Goel, 2011).

Practical tip: Advocate for mental health professionals on school staff and share helpline resources openly.

8. Model Empathy and Compassion

Perhaps the most powerful intervention is modeling empathetic behavior. Children who observe empathy in adults are more likely to internalize it, creating supportive peer cultures (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

Practical tip: Use active listening techniques—eye contact, paraphrasing, and withholding judgment—to demonstrate empathy.

The Role of Early Intervention in Prevention

Early intervention not only alleviates current distress but also prevents long-term mental health issues. Meta-analyses show that school-based prevention programs reduce the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders (Durlak et al., 2011). When parents and teachers respond quickly and empathetically, students learn that seeking help is safe and effective.

Challenges to Implementing Early Intervention

- Resource limitations: Many schools lack trained mental health professionals.

- Stigma: Families may resist intervention due to cultural or societal stigma.

- Overburdened teachers: Educators may feel unequipped to address mental health.

- Privacy concerns: Confidentiality must be balanced with safety.

Despite these challenges, even small actions—listening, checking in, and validating feelings—can have significant positive effects.

Conclusion

Youth mental health is foundational for lifelong well-being. With rising rates of anxiety, depression, and stress among students, early intervention has never been more important. Parents and teachers play critical roles as the first line of defense, capable of recognizing early signs and offering timely support.

By fostering open communication, teaching resilience, reducing stigma, and collaborating across home and school contexts, adults can create environments where students not only survive but thrive. Mental health support does not require perfection—it requires presence, empathy, and consistency. Together, parents and teachers can transform early intervention into a collective strength that shapes healthier futures for all children.

References

Ackard, D. M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Perry, C. (2006). Parent–child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics, 32(3), 483–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002

Christenson, S. L., & Sheridan, S. M. (2001). Schools and families: Creating essential connections for learning. Guilford Press.

Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

Dewald, J. F., Meijer, A. M., Oort, F. J., Kerkhof, G. A., & Bögels, S. M. (2010). The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration, and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine, 14(3), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.009

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Kern, L., Harrison, J. R., & Cook, C. R. (2017). Student mental health: Addressing needs through comprehensive school-based services. School Psychology Review, 46(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0025.V46-2

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2019). Integrating nutrition, mental health, and eating disorder prevention into public health efforts: What we know and where to go from here. American Journal of Public Health, 109(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304882

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022714

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Oberle, E., Lawlor, M. S., Abbott, D., Thomson, K., Oberlander, T. F., & Diamond, A. (2015). Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038454

Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S., & Thapar, A. K. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4

World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent mental health. World Health Organization.

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 603. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 8). Youth Mental Health and 8 Effective Early Intervention Strategies. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/youth-mental-health/