Introduction

Most people have experienced the peculiar phenomenon of a song looping in their minds long after it has stopped playing. This involuntary mental replay of music is known as an “earworm,” or, in scientific terms, involuntary musical imagery (INMI). Earworms can be pleasant, mildly irritating, or even disruptive, depending on their persistence and the listener’s state of mind. While often dismissed as a quirky aspect of human cognition, the underlying neuroscience reveals a complex interplay between memory, auditory processing, and individual personality traits. Understanding why certain tunes become stuck — and why some people are more vulnerable than others — offers a window into the intricate workings of the human brain.

Read More: GenZ Hates Phone Calls

What Makes a Tune “Sticky”

Not all songs have equal potential to become earworms. Research suggests that earworm-inducing songs tend to share specific musical features: simple, repetitive structures, mid-range tempos, and a balance between predictability and novelty (Jakubowski, Finkel, Stewart, & Müllensiefen, 2014). These elements make a song easy for the brain to encode and retrieve, while the slight novelty keeps it engaging.

Familiarity also plays a critical role. The “mere exposure effect” — the psychological tendency to develop preferences for things simply because they are familiar — increases the likelihood of a song becoming mentally lodged (Zajonc, 1968). This is why the most frequent earworms are often current pop hits or jingles heard repeatedly in advertisements.

How the Brain Processes Earworms

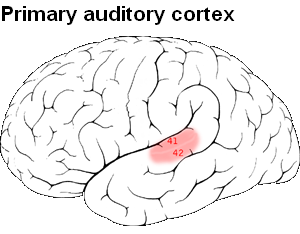

Neuroscientific studies using brain imaging reveal that when a person recalls or imagines a song, many of the same neural regions activate as when they hear it aloud (Halpern & Zatorre, 1999). The auditory cortex plays a central role in representing the pitch and timbre, while the motor cortex is thought to contribute to rhythmic aspects, perhaps through subtle subvocalization — silent “singing along” that keeps the loop going (Beaman & Williams, 2010).

The persistence of earworms is linked to working memory systems and the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which becomes active when attention is not focused on an external task (Smallwood & Schooler, 2015). In this “mind-wandering” state, fragments of songs can resurface, particularly if they are well-encoded and emotionally salient. This may explain why earworms often emerge during repetitive activities like walking or showering.

Why Some Brains Are More Vulnerable

While nearly everyone experiences earworms, some individuals are more susceptible. Personality research indicates that people high in openness to experience and neuroticism report more frequent and longer-lasting earworms (Beaman & Williams, 2013). Individuals with obsessive-compulsive tendencies may also find them harder to shake, possibly due to heightened attentional focus on unwanted thoughts (Williamson et al., 2014).

Musical training is another factor: musicians tend to experience more earworms, likely because of their enhanced auditory imagery skills and stronger neural connections in music-related brain regions (Liikkanen, 2012). Emotional context matters as well — songs tied to strong personal memories or emotions are more likely to get stuck because they engage both emotional (limbic) and cognitive (cortical) brain systems.

Coping Strategies and Interruption Techniques

Although earworms are generally harmless, they can become distracting, particularly for individuals prone to anxiety or obsessive thought patterns. Research has identified several strategies to interrupt or minimize them. Effective techniques include:

- Musical closure – Listen to the song in full to provide the brain with a sense of completion (Beaman & Williams, 2010).

- Cognitive distraction – Engage in a mentally demanding activity such as solving puzzles, doing math problems, or reading complex text.

- Chewing gum – This interferes with subvocal rehearsal in the articulatory loop of working memory (Beaman, 2015).

- “Cure songs” – Play a bland or neutral piece of music to displace the earworm, while avoiding songs that could themselves become stuck.

However, the effectiveness of these strategies can vary from person to person, depending on cognitive style, current mood, and even recent exposure to other music.

The Adaptive Side of Earworms

Interestingly, earworms may not be entirely maladaptive. They could serve as a kind of memory rehearsal mechanism, reinforcing musical patterns or lyrics for later retrieval (Jakubowski et al., 2014). From an evolutionary perspective, the brain’s ability to latch onto and repeat auditory information may have once been useful for learning language, songs, and oral traditions. In this way, earworms might represent a harmless byproduct of a cognitive system optimized for pattern recognition and memory consolidation.

Conclusion

Earworms, though sometimes bothersome, are a testament to the brain’s remarkable capacity for auditory imagery, memory encoding, and emotional association. Catchy tunes exploit specific musical features that align with how the brain processes and recalls sound, and individual differences in personality, experience, and emotional state determine susceptibility. While there are effective strategies to manage persistent earworms, most are fleeting and benign — small reminders of the brain’s tendency to replay what it finds salient, pleasurable, or important. Far from being mere nuisances, earworms reveal much about how human cognition intertwines with music, memory, and emotion.

References

Beaman, C. P. (2015). Interrupting the “irrepressible” earworm: Background music and articulatory suppression suppress involuntary musical imagery. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68(7), 1350–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2014.966728

Beaman, C. P., & Williams, T. I. (2010). Earworms (‘stuck song syndrome’): Towards a natural history of intrusive thoughts. British Journal of Psychology, 101(4), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X479636

Beaman, C. P., & Williams, T. I. (2013). Individual differences in susceptibility to involuntary musical imagery. Psychology of Music, 41(5), 638–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735612469670

Halpern, A. R., & Zatorre, R. J. (1999). When that tune runs through your head: A PET investigation of auditory imagery for familiar melodies. Cerebral Cortex, 9(7), 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/9.7.697

Jakubowski, K., Finkel, S., Stewart, L., & Müllensiefen, D. (2014). Dissecting an earworm: Melodic features and song popularity predict involuntary musical imagery. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036840

Liikkanen, L. A. (2012). Musical activities predispose to involuntary musical imagery. Psychology of Music, 40(2), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735611406578

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

Williamson, V. J., Liikkanen, L. A., Jakubowski, K., & Stewart, L. (2014). Sticky tunes: How do people react to involuntary musical imagery? PLoS One, 9(1), e86170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086170

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,027 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 14). Why “Earworms” Get Stuck and 4 Unique Ways to Cope With It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/why-earworms-get-stuck/