Imagine waking up, opening your phone, and finding thousands of people dumping buckets of ice water on their heads, dancing to the same 15-second track, or balancing brooms because “NASA said so.” These moments feel silly, spontaneous, and random—yet they often sweep across the globe in days. Welcome to the fascinating world of viral challenges.

But why do humans—rational, thinking beings—suddenly feel compelled to throw themselves into risky, funny, or downright bizarre viral challanges? The answer lies in social contagion, a psychological process that explains how thoughts, emotions, and behaviors spread like wildfire in groups.

Read More: Digital Burnout

The Roots of Social Contagion

Social contagion refers to the spread of behaviors and emotions within a group, much like the way a yawn can ripple through a room (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994). Online, this effect is amplified because we’re not just yawning in a classroom; we’re yawning in front of billions.

Researchers have long shown that humans are copycats by nature. We imitate gestures, adopt slang, and mirror social norms without realizing it. Viral challenges are simply the 21st-century extension of this ancient instinct—except now the “village” is global, and the “campfire” is TikTok.

The Dopamine Loop

Every time someone posts a video of themselves dancing to the same track as millions of others, they are plugging into a powerful dopamine loop. Likes, shares, and comments trigger the brain’s reward system (Meshi, Tamir, & Heekeren, 2015).

What makes challenges special is that they offer both structure and creativity. You’re not inventing something from scratch; you’re joining a trend that already comes with a ready-made script. The rules are clear: pour the ice water, nail the dance, flip the bottle. But there’s also room to remix it—make it funny, dramatic, or personal. This balance is dopamine gold: predictable reward with a dash of novelty.

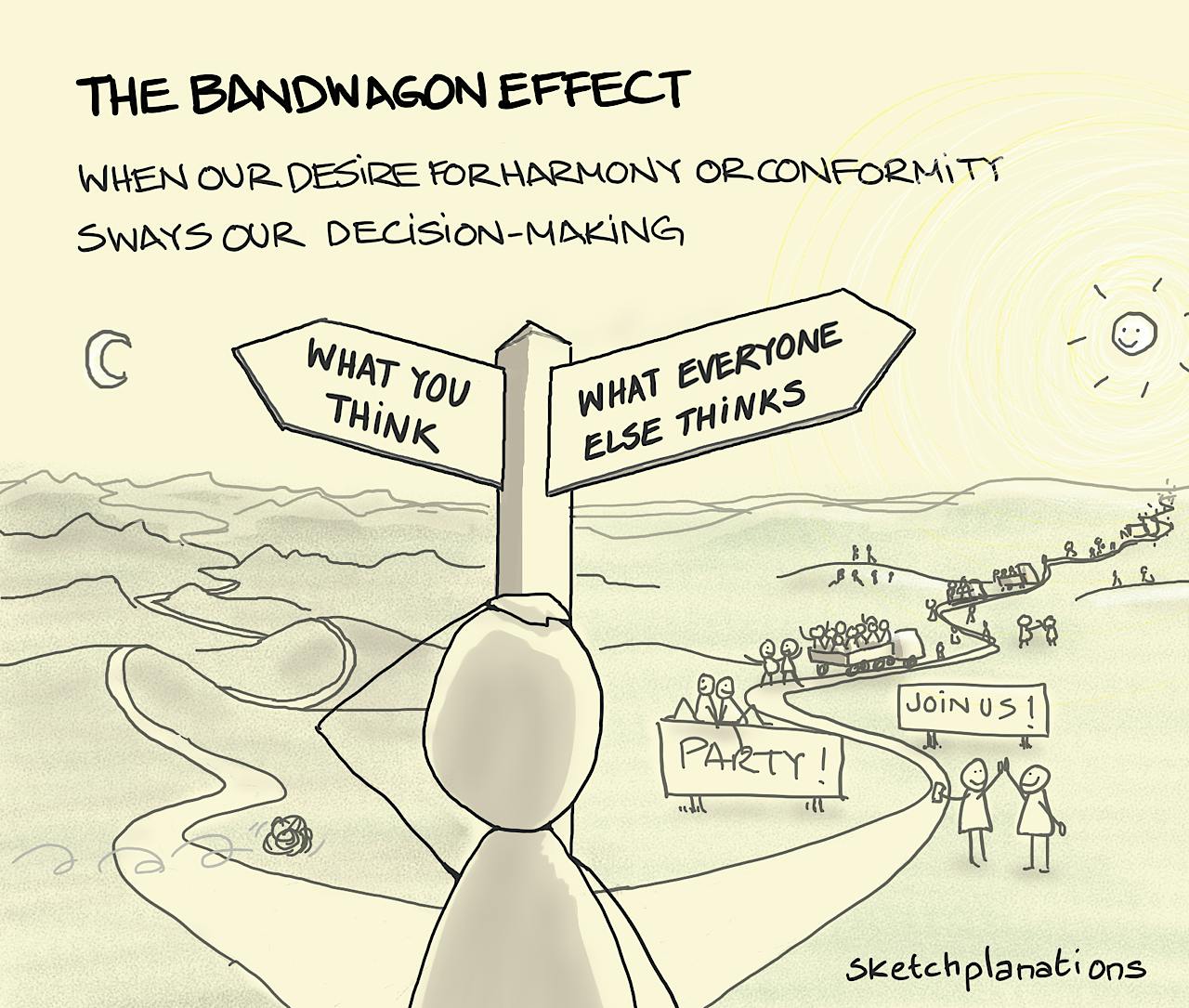

The Bandwagon Effect and Conformity

Think back to the classic Asch conformity experiments (Asch, 1955). When people were asked to match line lengths, many went along with an obviously wrong answer just because others did. Viral challenges operate on the same principle.

When your feed is full of friends, celebrities, or strangers doing the same thing, the “social proof” is overwhelming. Psychologists call this the bandwagon effect—we adopt behaviors simply because “everyone else is doing it.” Online, this effect is magnified by algorithms that prioritize viral content, making challenges impossible to ignore.

FOMO

Viral challenges thrive on FOMO. Not participating can feel like missing an inside joke shared by millions.

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) suggests that people define themselves through group membership. By joining a viral challenge, you’re signaling: I’m part of the global tribe, I get it, I belong. The pressure is real—skip the challenge, and you risk feeling like an outsider.

The Role of Storytelling and Narrative

Challenges also go viral because they tell a story. The Ice Bucket Challenge wasn’t just about dumping water—it was about raising awareness and funds for ALS. The “10-Year Challenge” wasn’t just about photos—it was about reflecting on personal growth. Even silly ones (like bottle-flipping) create micro-stories of suspense, success, and failure.

Humans are wired for narrative (Gottschall, 2012). A viral challenge is essentially a story you can step into—one that already has a beginning, middle, and end. And by participating, you add your own chapter.

Memetics

Richard Dawkins (1976) introduced the concept of “memes” as cultural units that spread like genes. Viral challenges are the perfect example of memes in action—self-replicating behaviors that evolve as they spread.

Take the “Harlem Shake.” The original had one format: calm scene, sudden chaos. Within weeks, the meme mutated into countless versions—office workers, firefighters, students, even underwater divers. Challenges don’t just spread; they evolve, adapting to each new cultural context.

The Dark Side

Of course, not all viral challenges are harmless fun. Some—like the “Tide Pod Challenge” or the “Blackout Challenge”—are dangerous. Why do people still participate?

Part of the answer lies in sensation-seeking behavior (Zuckerman, 1994). Teenagers and young adults, whose prefrontal cortex (responsible for impulse control) is still developing, are especially drawn to high-risk, high-reward behaviors. Add peer pressure and the global stage of the internet, and risky challenges become tempting tickets to instant fame.

Why We Love Watching (Even if We Don’t Participate)

Interestingly, you don’t need to take part to feel included. Watching viral challenges offers a sense of vicarious belonging. Psychologists call this parasocial interaction—the illusion of friendship or connection with people you see online (Horton & Wohl, 1956).

Even if you never danced the “Renegade,” watching others do it makes you part of the cultural conversation. Participation by proxy is still participation.

What Viral Challenges Reveal About Us

So what do all these ice buckets, dances, and bottle flips tell us about human psychology?

-

We are deeply social creatures—wired to imitate, connect, and belong.

-

We love stories and rituals—even tiny ones like repeating a challenge format.

-

We balance conformity with individuality—joining the crowd while adding a personal twist.

-

We crave dopamine and validation—and social media delivers it in abundance.

Viral challenges might look silly on the surface, but they’re windows into ancient human behaviors—identity formation, storytelling, ritual, and community-building—repackaged for the digital age.

Conclusion

The next time you see millions of people doing the same quirky dance, remember: it’s not just fun, it’s psychology in motion. Viral challenges catch on because they activate primal instincts—our need to belong, to copy, to play, and to share.

In a way, every viral challenge is a giant global campfire. And around it, billions of us gather—not just to laugh, but to remind ourselves that we’re part of something bigger.

References

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 193(5), 31–35.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

Gottschall, J. (2012). The storytelling animal: How stories make us human. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion. Cambridge University Press.

Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and parasocial interaction. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229.

Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I., & Heekeren, H. R. (2015). The emerging neuroscience of social media. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(12), 771–782.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 3). Why Viral Challenges Catch On and 4 Important Things It Reveals About Us. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/viral-challenges-catch-on/