Introduction

We often think of cities as symbols of opportunity: bustling streets, glittering skylines, endless culture, and convenience. Yet, as more than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas a figure expected to rise to nearly 70% by 2050 (United Nations, 2018) scientists are uncovering how cities profoundly affect our mental health. Far beyond mere background scenery, urban environments can stress or soothe our brains in surprising ways.

Read More- Hustle Culture

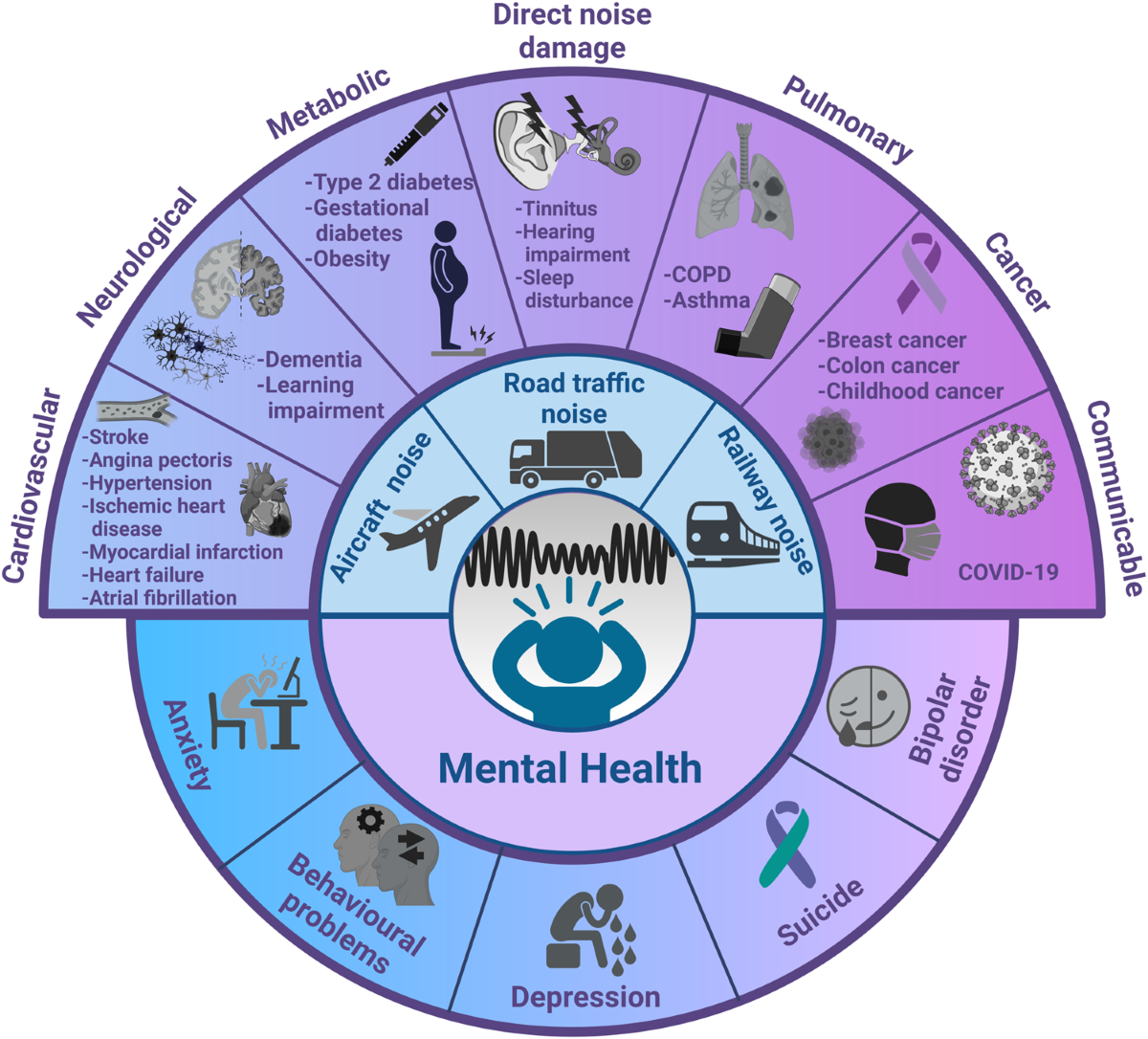

1. Noise Pollution

Picture trying to meditate while a jackhammer roars outside. That’s a daily reality for many urbanites. Chronic exposure to environmental noise — traffic, sirens, construction — has been strongly linked to increased stress hormones, sleep disturbances, and cardiovascular risk (Basner et al., 2014).

But the mental health implications are just as striking. One large-scale study found higher rates of depression and anxiety among those exposed to persistent noise above 55 dB (Orban et al., 2016). Researchers suggest that noise triggers our sympathetic nervous system — the fight-or-flight response — even when we’re not consciously aware of it, keeping us in a state of low-level vigilance that drains emotional reserves (Babisch, 2011).

Fun fact: People living near busy airports have been shown to have significantly higher rates of depression (Seidler et al., 2017). Turns out, a 747’s takeoff isn’t just hard on the ears — it’s hard on the mind.

What can help? Urban planners are experimenting with “soundscaping,” like planting dense rows of trees or installing water features that mask harsh noises with calming sounds (Aletta et al., 2018).

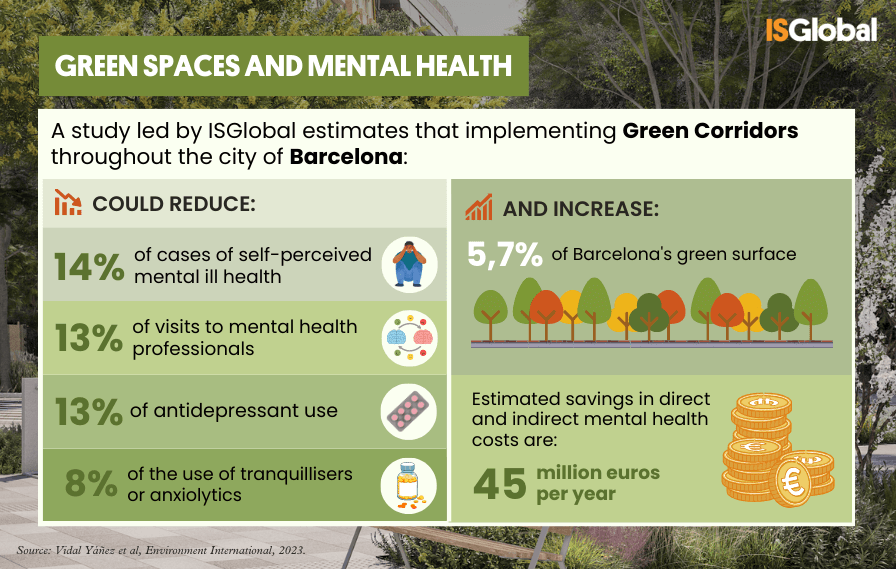

2. Green Spaces

Ever noticed how a walk in the park can lift your mood? You’re not imagining it: nature is a powerful antidote to urban stress.

One landmark experiment at Stanford found that a 90-minute walk in a natural setting decreased rumination — the repetitive negative thoughts common in depression — and reduced activity in the brain’s subgenual prefrontal cortex, a region linked to mood disorders (Bratman et al., 2015).

Living near green spaces has been associated with lower levels of anxiety, depression, and even improved cognitive development in children (Dadvand et al., 2015). Researchers believe that natural environments provide “soft fascination,” gently capturing attention without overwhelming it, giving the brain a chance to rest and recover (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989).

Fun fact: Hospital patients with a window view of trees recovered faster and needed less pain medication than those facing a brick wall (Ulrich, 1984).

What can help? Urban designers advocate for “biophilic cities,” weaving greenery into rooftops, walls, and public spaces to create daily doses of nature for city dwellers.

3. Crowding and Social Density

Cities offer unparalleled social opportunities — but they also mean sharing space with millions of strangers. High population density can create feelings of crowding, leading to stress, aggression, and social withdrawal (Evans, 2001). In animals, overcrowding has been shown to increase aggression and decrease fertility — a phenomenon sometimes called the “behavioral sink” (Calhoun, 1962). While humans aren’t rats, our brains still register dense, chaotic environments as stressful.

Yet, it’s not just the number of people but how we interact with them that matters. High-density urban neighborhoods can either promote community — like vibrant street life and shared spaces — or breed isolation if they lack social cohesion.

Fun fact: A study in Stockholm found that people who felt lonely in densely populated areas had a 70% higher risk of depression than those who felt socially connected (Frumkin, 2003).

What can help? Mixed-use neighborhoods, community gardens, and public squares can turn density into an opportunity for connection rather than a source of alienation.

4. Built Environment and Cognitive Function

The way cities are designed — from street layouts to building heights — affects how easily we navigate them and how mentally taxed we feel.

Grid-like street patterns, clear signage, and landmarks help people find their way, reducing cognitive load and anxiety (Hölscher et al., 2006). By contrast, disorienting mazes of identical buildings and confusing intersections can impair spatial memory and make daily routines more stressful.

Architectural complexity, like diverse facades or playful design elements, can stimulate curiosity and positive emotions, while monotonous, sterile environments are associated with lower mood and even cognitive fatigue (Lindal & Hartig, 2015).

Fun fact: Research using fMRI has shown that when people navigate complex virtual cities without landmarks, their brains show greater activation in the hippocampus — the region involved in stress and memory — compared to when they navigate more legible, landmark-rich environments (Javadi et al., 2017).

What can help? Human-centered design, which prioritizes walkability and visual variety, supports both mental well-being and easier wayfinding.

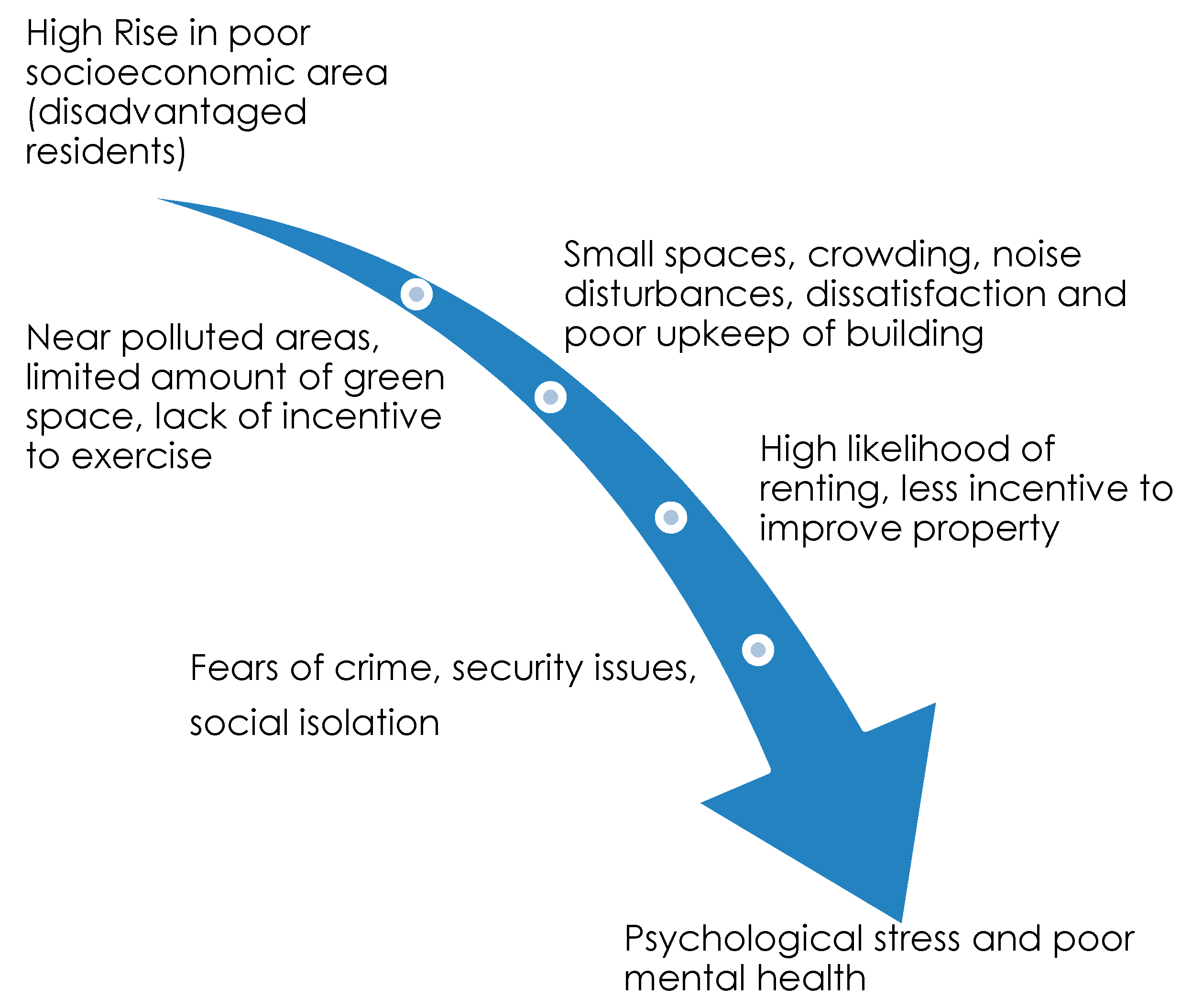

5. Socioeconomic Disparities

Cities are places of stark contrasts: gleaming high-rises can stand next to overcrowded, underserved neighborhoods. Such inequalities aren’t just economic — they map onto mental health, too.

Children growing up in disadvantaged urban areas face higher risks of cognitive delays, behavioral issues, and adult psychiatric disorders (Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). Chronic exposure to poverty, crime, and unstable housing creates toxic stress that can reshape the developing brain, leading to heightened emotional reactivity and impaired executive function (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

Neighborhood-level factors — like social cohesion, access to resources, and perceived safety — strongly predict mental health outcomes, even after accounting for individual income (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996).

Fun fact: In a famous study, moving families from high-poverty to lower-poverty neighborhoods improved parents’ mental health and increased children’s long-term educational and economic outcomes (Chetty et al., 2016).

What can help? Equitable urban planning, like mixed-income housing and investment in underserved communities, can break the cycle of place-based disadvantage.

Bringing It All Together

Urban environments shape our mental health through noise, nature access, crowding, design, and inequality. These factors interact: a noisy, treeless, confusing, and impoverished neighborhood compounds risk, while a green, connected, well-designed, and equitable one can protect and nourish the mind.

As cities continue to grow, prioritizing mental health in urban design isn’t a luxury — it’s essential for sustainable, thriving communities.

References

Aletta, F., Oberman, T., Mitchell, A., Erfanian, M., Lionello, M., Kachlicka, M., & Kang, J. (2018). Associations between soundscape experience and self-reported wellbeing in open public urban spaces. Cities, 87, 49–56.

Aneshensel, C. S., & Sucoff, C. A. (1996). The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37(4), 293–310.

Babisch, W. (2011). Cardiovascular effects of noise. Noise and Health, 13(52), 201–204.

Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., Janssen, S., & Stansfeld, S. (2014). Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet, 383(9925), 1325–1332.

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2015). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249(1), 118–136.

Calhoun, J. B. (1962). Population density and social pathology. Scientific American, 206(2), 139–148.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902.

Dadvand, P., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Esnaola, M., Forns, J., Basagaña, X., Alvarez-Pedrerol, M., … & Sunyer, J. (2015). Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(26), 7937–7942.

Evans, G. W. (2001). Environmental stress and health. In A. Baum, T. A. Revenson, & J. E. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of Health Psychology (pp. 365–385). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Frumkin, H. (2003). Healthy places: exploring the evidence. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1451–1456.

Hölscher, C., Büchner, S., & Strube, G. (2006). Multi-level modeling of wayfinding behavior in buildings. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 33(5), 705–724.

Javadi, A. H., Patai, E. Z., Marin-Garcia, E., Margolis, A., Tan, H. M., Kumaran, D., & Spiers, H. J. (2017). Hippocampal and prefrontal processing of network topology to simulate the future. Nature Communications, 8(1), 14652.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Kim-Cohen, J., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., & Taylor, A. (2003). Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The importance of considering both neighborhood and family characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(6), 1051–1060.

Lindal, P. J., & Hartig, T. (2015). Architectural variation, building height, and the restorative quality of urban residential streetscapes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 122–130.

Orban, E., McDonald, K., Sutcliffe, R., Hoffmann, B., Fuks, K. B., Dragano, N., & Erbel, R. (2016). Residential road traffic noise and high depressive symptoms after five years of follow-up: Results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(5), 578–585.

Seidler, A., Hegewald, J., Seidler, A. L., Schubert, M., Wagner, M., Droge, P., … & Zeeb, H. (2017). Association between aircraft, road and railway traffic noise and depression in a large case-control study based on secondary data. Environmental Research, 152, 263–271.

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., & the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421.

United Nations. (2018). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,041 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 8). 5 Dynamic Ways In Which Urban Environment Shapes Our Mental Health. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/urban-environment-shapes-our-mental-health/