Introducing a New Series on Stress

Stress has become a common experience in today’s fast-paced world, impacting nearly every aspect of our lives. From work pressures to personal challenges, stress can feel overwhelming if left unmanaged.

To help navigate this complex topic, we are launching a comprehensive series on stress, exploring everything from what stress is, to the different types of stress, and how it affects our physical and mental health. Over the course of this series, we will also delve into effective coping strategies, practical lifestyle changes, and techniques to build resilience against stress.

In this first article, we will start by understanding the fundamentals of stress- what it is, the science behind it, and how it impacts us both in the short and long term. By grasping the nature of stress, we can begin to manage it more effectively and enhance our overall well-being.

Understanding Stress

Stress is a universal experience that impacts everyone, though its causes and effects vary from person to person. While often viewed negatively, stress is an essential biological mechanism that plays a crucial role in human survival.

Definition of Stress

Stress is a physiological and psychological response to perceived threats or challenges. It occurs when external or internal demands exceed an individual’s perceived ability to cope.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), stress is “a normal reaction to everyday pressures” but becomes harmful when chronic or overwhelming .

Some important definitions of stress are-

- Stress is defined as a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

- Stress is the adverse reaction people have to excessive pressures or other types of demand placed on them (WHO, n.d.)

- Stress is viewed as a process that involves the individual’s perception of the stressor and the ability to cope with it, leading to allostatic load, which represents the wear and tear on the body and mind due to prolonged or repeated stress responses (McEwen, 1998).

- Stress is the non-specific response of the body to any demand placed upon it. It is a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or demanding circumstances (Selye, 1976).

- Stress is a psychological phenomenon that occurs in response to perceived environmental demands that are appraised as exceeding an individual’s resources and compromising their well-being (Engel, 1997).

- Stress is an automatic response to perceived danger that prepares the body to either confront or flee from the threat, leading to physiological changes such as increased heart rate and adrenaline release (Cannon, 1932).

- Stress is a phenomenon that arises from the discrepancy between one’s self-concept and one’s experience, leading to feelings of incongruence and emotional distress (Rogers, 1961).

- Stress is a result of cognitive distortions that lead individuals to perceive situations as more threatening or challenging than they truly are, impacting their emotional well-being (Beck, 1975).

- Stress is the body’s response to a perceived threat, resulting in a cascade of hormonal changes that prepare the body for immediate action but can lead to long-term health issues if persistent (Sapolsky, 2004).

- Stress is a response that occurs when individuals perceive that they do not have the resources to cope with perceived threats or challenges, leading to negative emotions and health outcomes (Friedrickson, 2001).

Good Stress Vs Bad Stress

Research highlights the distinction between eustress (positive stress) and distress (negative stress). Eustress, a term first introduced by Hans Selye in 1974, motivates individuals to perform better and enhances overall well-being. It can lead to improved performance in tasks requiring focus and alertness . Conversely, distress results from overwhelming challenges and can lead to emotional and physical harm, including chronic diseases .

Read More- Types of Stress

Read More- What is Mental Health

Why Stress Is a Natural Response?

Stress evolved as an essential survival tool for humans. The fight-or-flight response, first described by Walter Cannon in 1915, is the body’s immediate reaction to danger, preparing us to either face or flee from threats . This response, though beneficial in short bursts, becomes detrimental when activated repeatedly or over prolonged periods due to non-life-threatening modern stressors, like work pressure or financial concerns.

Read More- What is My Stress Level

The Science of Stress

How Does Stress Affects the Body?

When we encounter a stressor, the brain signals the release of stress hormones that prime the body for action. This fight-or-flight response involves a cascade of physiological changes, such as increased heart rate, heightened alertness, and the diversion of blood flow from non-essential organs to muscles . While this system is crucial for short-term survival, chronic activation can lead to health issues.

The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), which governs involuntary functions like heart rate and digestion, is key to stress regulation. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activates the body’s fight-or-flight response, while the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) is responsible for calming the body down after a stressful event. Studies have shown that imbalances between these systems, particularly chronic over-activation of the SNS, can contribute to stress-related disorders such as hypertension and anxiety .

Stress Hormones

Cortisol and adrenaline are the primary hormones released during stress.

Adrenaline increases heart rate and energy levels, while cortisol maintains energy by regulating blood sugar and suppressing non-essential functions, such as digestion.

A study by McEwen (1998) demonstrated that chronic elevation of cortisol can lead to negative health outcomes, including weakened immunity, memory impairment, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease .

HPA Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is a central component of the body’s response to stress. It plays a crucial role in regulating the release of stress hormones, primarily cortisol, and helps the body adapt to stress over time. When the HPA axis is activated, it initiates a cascade of hormonal signals that allow the body to cope with stress, but prolonged activation can lead to health problems.

The HPA axis is a complex set of interactions between three major glands in the endocrine system-

- Hypothalamus– Located in the brain, the hypothalamus is responsible for maintaining homeostasis and regulating several bodily functions. It acts as the control center in the stress response.

- Pituitary gland– Often called the “master gland,” the pituitary, located just below the hypothalamus, releases hormones that regulate various endocrine glands throughout the body.

- Adrenal glands– Located on top of the kidneys, the adrenal glands produce cortisol, adrenaline, and other hormones involved in the stress response.

When a person perceives a stressor, whether physical (e.g., injury, infection) or psychological (e.g., work pressure, emotional distress), the hypothalamus activates the HPA axis. Here’s how the HPA Axis works-

- Activation of the Hypothalamus– Upon sensing stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the bloodstream.

- Pituitary Gland Stimulation– CRH travels to the pituitary gland, prompting it to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

- Adrenal Glands Response– ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to produce and release cortisol, the primary stress hormone, into the bloodstream. At the same time, the adrenal glands also release adrenaline, which contributes to the immediate fight-or-flight response by increasing heart rate, energy levels, and alertness.

- Cortisol’s Role– Cortisol helps the body manage stress by regulating several important functions like increasing blood sugar levels, suppressing non-essential functions, and modifying brain function to improve focus and decision-making under pressure.

- Negative Feedback Loop– Once the stressor is resolved, the negative feedback loop kicks in, signaling the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to reduce CRH and ACTH production, which in turn lowers cortisol levels, allowing the body to return to a state of balance.

While the HPA axis effectively manages short-term stress, chronic stress leads to prolonged activation and overproduction of cortisol, which can have harmful effects on the body, including:

- Immune suppression– Weakened immune response, increasing susceptibility to infections and slowing recovery.

- Weight gain and metabolic issues– Higher cortisol levels contribute to fat accumulation, especially in the abdomen, leading to obesity and metabolic disorders.

- Cardiovascular strain– Increased blood pressure and inflammation raise the risk of heart disease and stroke.

- Cognitive and mental health problems– Chronic stress can cause cognitive decline, memory issues, and mental health disorders like anxiety and depression due to the negative impact on the hippocampus.

- Sleep disturbances– Disruption of cortisol patterns can lead to sleep problems, exacerbating stress.

The HPA axis is central to how the body responds to stress, acting as a hormonal switchboard that triggers the release of cortisol and adrenaline. While short-term activation of the HPA axis helps the body deal with immediate threats, chronic stress overstimulates this system, leading to physical, mental, and emotional health issues over time.

How Does Stress Affect Me?

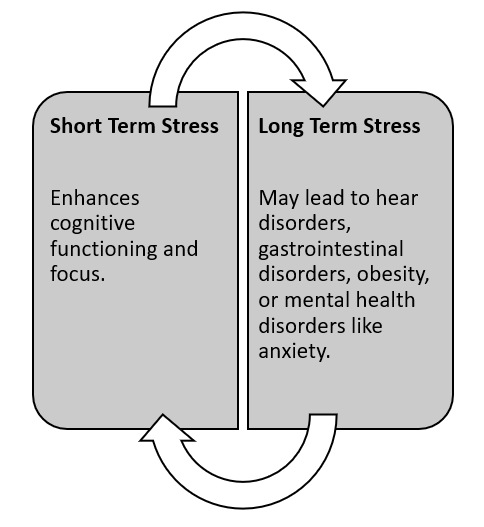

Way 1- Effects of Acute (Short-Term) Stress

Short-term, or acute stress, is the body’s immediate response to sudden challenges or demands. This type of stress is usually brief and can be triggered by situations like meeting a deadline, preparing for an important presentation, or handling an unexpected event. In these moments, the brain signals the release of stress hormones like adrenaline, which heighten our senses, increase energy levels, and prepare us for action.

Interestingly, research indicates that acute stress, when experienced in manageable doses, can actually enhance cognitive function. When the brain perceives a challenge, it ensures that more glucose and oxygen are delivered to key areas, particularly the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for higher-order thinking such as decision-making, problem-solving, and attention. This physiological boost helps us stay sharp and focused, allowing for improved performance under pressure.

For instance, a study by Joëls et al. (2006) demonstrated that short bursts of stress can improve memory and attention, particularly in situations that require quick thinking and adaptability. The study found that stress triggers a temporary enhancement of cognitive functions by optimizing the brain’s ability to process information, recall important details, and stay alert. This explains why some people perform better in high-stakes situations, such as athletes in competitions or students during exams.

However, once the stressful situation has passed, the body naturally shifts from its fight-or-flight state back to a more relaxed state. The parasympathetic nervous system kicks in, helping to restore balance by slowing the heart rate, calming the mind, and returning hormone levels to normal. This quick recovery ensures that acute stress typically does not have lasting negative effects on physical or mental health.

Way 2- Effects of Chronic (Long-Term) Stress

Chronic stress, unlike short-term stress, involves the prolonged activation of the body’s stress response. When stress becomes a constant presence, the body’s heightened state of alertness persists over time, which can lead to serious physical and mental health problems.

Physical Health Effects of Chronic Stress

Prolonged stress keeps the body in a state of overdrive, causing wear and tear on multiple systems. Research links chronic stress to conditions such as-

- Cardiovascular diseases– Chronic stress increases inflammation, blood pressure, and heart rate, all of which strain the heart and blood vessels. This significantly raises the risk of heart disease.

- Obesity– Elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol can promote fat accumulation, particularly around the abdomen, which is associated with a higher risk of metabolic diseases.

- Gastrointestinal disorders– Stress can disrupt digestion, leading to issues such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ulcers, and other digestive problems.

Study by Cohen et al. (2012) found that people who experienced long-term stress had a much higher risk of developing heart disease, with increased inflammation and sustained high blood pressure being key contributors to this elevated risk.

Mental Health Effects of Chronic Stress

- Anxiety– Constant stress keeps the brain in a heightened state of worry, often leading to chronic anxiety.

- Depression– Chronic stress depletes the brain’s ability to regulate mood, leading to a higher likelihood of depression.

- Cognitive decline– Long-term stress has been shown to impair memory, concentration, and other cognitive functions over time, with research suggesting a potential link to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Chronic stress not only affects the body’s systems but also plays a significant role in worsening mental health, contributing to a range of severe, long-lasting conditions.

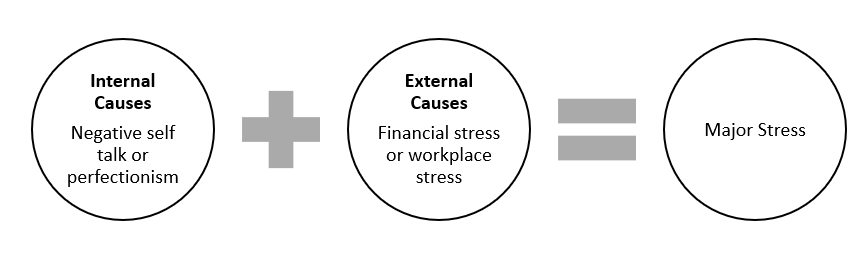

Common Causes of Stress

External Factors

External stressors often arise from situations where individuals feel a lack of control or face significant challenges. These include-

- Workplace stress– A 2020 study by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that long working hours and high job demands increase the risk of stroke and heart disease .

- Relationship stress– Relationship conflict has been shown to elevate cortisol levels, leading to prolonged stress .

- Financial stress– Studies indicate that financial insecurity is a significant predictor of both physical and mental health problems, including depression and anxiety .

- Major life events– Life changes such as moving, divorce, or bereavement can be significant sources of stress, contributing to emotional distress and a decline in physical health .

Internal Factors

Internal factors, or stressors that come from within, often stem from one’s thought patterns, self-expectations, and attitudes-

- Negative self-talk and perfectionism– Research has shown that individuals who engage in negative self-talk or have perfectionist tendencies are more likely to experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety .

- Self-expectations– Unreasonably high personal goals or the need for external validation can create persistent stress, as demonstrated in studies of academic pressure among students .

Read More- Sources of Stress

Read More- Easy Techniques to Improve Mental Health

Conclusion

Understanding stress is crucial for effectively managing it. While stress is a natural and necessary part of life, chronic exposure can lead to severe health consequences. Research-backed insights into stress and its impact on the body, mind, and emotions allow us to take proactive steps in managing stress. By recognizing the difference between eustress and distress, understanding the physiological mechanisms behind stress, and identifying common causes, we can better navigate stressful situations and improve our overall well-being.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Stress: The Different Kinds of Stress. Retrieved from- https://www.apa.org/topics/stress.

Ball, J., & Darby, I. (2022). Mental health and periodontal and peri‐implant diseases. Periodontology 2000, 90(1), 106-124.

Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 607-628.

Cannon, W. B. (1915). Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear, and Rage. New York: Appleton.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, Adaptation, and Disease: Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33-44.

Ulrich-Lai, Y. M., & Herman, J. P. (2009). Neural Regulation of Endocrine and Autonomic Stress Responses. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 397-409.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904.

Cohen, S., Gianaros, P. J., & Manuck, S. B. (2016). A Stage Model of Stress and Disease. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 456-463.

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M., & Prescott, C. A. (1999). Causal Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and the Onset of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 837-841.

World Health Organization. (2020). Long Working Hours and the Risk of Heart Disease and Stroke. Retrieved from- https://www.who.int.

Saxbe, D. E. (2008). Repetti, R. L. Cortisol Dysregulation in Couples. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(8), 794-799.

Sweet, E., Nandi, A., Adam, E. K., & McDade, T. W. (2013). The High Price of Debt: Household Financial Debt and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Health. Social Science & Medicine, 91, 94-100.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213-218.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Psychosomatic Medicine, 39(2), 77-88.

Selye, H. (1976). The Stress of Life. McGraw-Hill.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Occupational Health: Stress at the Workplace. Retrieved from WHO

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, October 19). Understanding Stress- Discover 2 Ways in Which Stress Affects You. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/understanding-stress/