Introduction

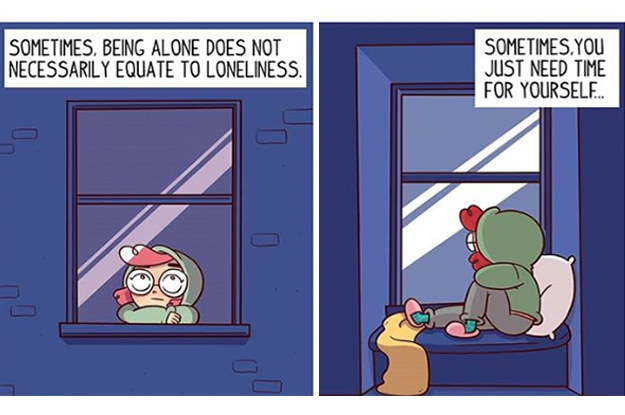

Imagine sitting in a cozy café by yourself, sipping coffee, watching people pass by, and feeling perfectly content. Now picture being in a crowded party where everyone seems busy laughing and chatting, yet you feel invisible and disconnected. Both scenarios involve being “alone,” but the emotional experience couldn’t be more different.

This is the paradox of human aloneness. Solitude can feel nourishing, peaceful, even inspiring. Loneliness, on the other hand, can feel heavy, painful, and isolating. The distinction between the two isn’t just semantics—it’s psychological gold. In fact, understanding the difference has implications for mental health, creativity, and even longevity.

Read More: Attention Economy

Defining the Terms

Understanding these terms is important.

What Is Loneliness?

Psychologists define loneliness as a distressing feeling that arises when there is a gap between desired and actual social connections. It’s less about the number of people around you and more about the quality of your relationships. A person with hundreds of social media followers can feel lonely if they lack meaningful bonds.

Loneliness isn’t just unpleasant—it’s linked to health risks. Research shows it is as harmful to mortality as smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Chronic loneliness is associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline.

What Is Solitude?

Solitude, in contrast, is the voluntary choice to be alone without feeling lonely. It is time spent with oneself, often experienced as restorative and enriching. Winnicott (1958), a psychoanalyst, described the “capacity to be alone” as a hallmark of psychological maturity. In solitude, people may reflect, recharge, or engage in creative pursuits.

Why Loneliness Hurts

Some of the reasons why loneliness hurts:

Evolutionary Roots

From an evolutionary perspective, humans are wired for connection. Our ancestors relied on group living for protection and survival. Being isolated meant vulnerability to predators or starvation. That deep wiring is still with us: when we feel lonely, the brain interprets it as a survival threat.

Biological Toll

Loneliness activates the stress response system. Levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, rise, which can impair immune function, increase inflammation, and disrupt sleep. Cacioppo and colleagues (2006) found that loneliness predicts poorer cardiovascular health and reduced resistance to illness. In short: loneliness doesn’t just hurt emotionally, it chips away at physical health.

Why Solitude Heals

Some of the ways that solitude heals include:

Space for Reflection

Solitude provides psychological breathing room. When we step away from constant social stimulation, we can reflect, regulate emotions, and gain clarity. Larson (1990) found that adolescents who engaged in intentional solitude reported higher self-acceptance and better coping skills.

Boosting Creativity

History is full of artists, writers, and thinkers who embraced solitude. Virginia Woolf insisted on “a room of one’s own.” Einstein valued solitude as the birthplace of ideas. Neuroscientific research suggests that in solitude, the “default mode network” of the brain is activated—this network supports self-reflection, imagination, and creative problem solving.

Emotional Regulation

Solitude can help regulate emotions. Nguyen et al. (2018) found that people who chose to spend 15 minutes alone experienced lower levels of anger and anxiety. Importantly, this was chosen solitude—when aloneness feels forced, the benefits vanish.

The Fine Line Between Solitude and Loneliness

The tricky part is that solitude and loneliness often blur. Both involve being alone, but the emotional interpretation makes the difference.

-

Loneliness = unwanted aloneness, linked to distress.

-

Solitude = chosen aloneness, linked to growth.

The same external condition (sitting by yourself) can be framed as empowering or isolating depending on mindset, context, and needs.

Example: The Library vs. The Cafeteria

-

In a library, sitting alone might feel productive and peaceful.

-

In a cafeteria full of chatting peers, sitting alone might feel embarrassing or lonely.

Context shapes the narrative.

The Role of Culture

How solitude is valued differs across cultures.

-

In Western societies, independence is prized, so solitude may be seen as self-care or creativity.

-

In collectivist societies, group belonging is emphasized, so too much solitude may be seen as abnormal or selfish.

Even within cultures, generational differences matter. Many young people raised in digital environments find solitude uncomfortable, having been constantly connected through devices.

Transforming Loneliness into Solitude

Here’s the good news: loneliness isn’t a permanent state. With reframing and practice, unwanted aloneness can sometimes be turned into nourishing solitude.

1. Shift the Narrative

Loneliness says, “I’m alone because no one wants me.” Solitude says, “I’m alone because I value this time.” Changing the story we tell ourselves about being alone can change the emotional experience.

2. Intentional Activities

Loneliness often festers when we’re idle. Solitude flourishes when we use time alone for intentional activities: journaling, painting, reading, meditating, walking.

3. Balance Social and Solo Time

We don’t have to choose between being hermits or social butterflies. Healthy psychological life includes both meaningful social connections and fulfilling alone time.

4. Practice “Micro-Solitudes”

Even a few minutes of daily solitude can be restorative. Turning off notifications, going for a short walk, or drinking tea quietly can serve as mini resets.

Fun Applications of Solitude

Want to make solitude playful instead of dreary? Try these:

-

Solo Dates: Take yourself to a movie, museum, or restaurant. Treat yourself the way you’d treat a friend.

-

Creative Challenges: Set aside an hour of solitude for doodling, writing, or inventing something silly.

-

Nature Therapy: Go for a solo hike. Being alone in nature amplifies the restorative effects.

-

Digital Detox: Spend one hour without screens. Notice what thoughts and feelings surface.

When Solitude Becomes Problematic

Of course, solitude isn’t always positive. Extended isolation without meaningful connection can slide into loneliness, depression, or social withdrawal. The key difference is choice. Chosen solitude heals; enforced solitude wounds.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, many people experienced forced isolation that felt more like loneliness than solitude. Rates of depression and anxiety spiked worldwide. This highlighted how much autonomy matters: even introverts struggled when solitude was mandatory.

Conclusion

Solitude and loneliness are two sides of the same coin of aloneness. Loneliness is painful, eroding both mental and physical health. Solitude, by contrast, is powerful, providing space for creativity, reflection, and emotional restoration. The difference lies in perception and choice.

By reframing alone time, practicing intentional solitude, and balancing it with meaningful social connections, we can harness solitude as a tool for growth instead of fearing it as loneliness. Next time you’re by yourself, ask: am I lonely, or am I simply in solitude? The answer might change how you experience your own company.

References

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

Larson, R. W. (1990). The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10(2), 155–183.

Nguyen, T. T., Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). The positive effects of solitude on mood and self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92–106.

Winnicott, D. W. (1958). The capacity to be alone. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 416–420.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 23). Explore 4 Important Ways to Transform Loneliness to Solitude. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/transform-loneliness-to-solitude/