Introduction

Time is a fundamental dimension of human experience, intricately woven into the fabric of our daily lives. Yet, our perception of time is not a fixed, objective measure; it is a subjective experience influenced by a myriad of psychological, physiological, and environmental factors.

The Construct of Time Psychology

In psychology and neuroscience, time psychology, or chronoception, refers to the subjective experience of time, encompassing how we perceive durations, the sequence of events, and the intervals between them. Unlike the physical measurement of time, our perception is malleable and can vary significantly based on internal and external influences.

Neural Mechanisms of Time Psychology

The brain does not possess a singular, centralized clock to track time. Instead, time perception arises from the dynamic interplay of various neural processes. Cognitive functions such as attention, working memory, and long-term memory are pivotal in shaping our temporal judgments. For instance, when attention is focused on a task, time may seem to pass quickly, whereas during periods of boredom or anticipation, it may appear to drag (Wittmann, 2009).

Moreover, the brain’s internal states, including emotions and physiological conditions, can alter time perception. Emotional arousal, whether positive or negative, often leads to a distortion in the perceived passage of time. High arousal states can make time seem to speed up or slow down, depending on the context and individual differences (Droit-Volet & Meck, 2007).

Read More- Gaslighting

Factors Influencing Time Perception

Several factors influence how we perceive time, ranging from emotional states to environmental contexts.

1. Emotional States

Emotions profoundly impact our sense of time. Negative emotions, such as sadness and anger, have been found to hasten the perception of time passing. This acceleration in perceived time may be attributed to the increased cognitive load and heightened awareness associated with negative emotional states (Droit-Volet & Gil, 2009).

Conversely, positive emotions can either speed up or slow down time perception, depending on the intensity and nature of the experience. Joyful and engaging activities often lead to a faster perception of time, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “time flying when you’re having fun.”

2. Attention and Cognitive Load

The allocation of attention plays a crucial role in time perception. When individuals are deeply engrossed in an activity, they may lose track of time, leading to an underestimation of elapsed time. This is because focused attention on a task reduces the cognitive resources available for monitoring the passage of time (Zakay & Block, 2004).

In contrast, when performing monotonous or unengaging tasks, individuals may overestimate the passage of time due to increased attention to time itself. High cognitive load can also distort time perception, as the brain’s processing capacity is taxed, leading to less accurate temporal judgments.

3. Physiological States

Our bodily states, including interoceptive signals (internal bodily sensations), influence time perception. Research suggests that heightened awareness of internal bodily states, such as heartbeat and respiration, can lead to a more accurate perception of time intervals. This connection between interoception and time perception highlights the embodied nature of how we experience time (Meissner & Wittmann, 2011).

4. Age and Development

Time perception evolves across the lifespan. Children often experience time as passing more slowly, likely due to the novelty of experiences and the developing nature of their cognitive processes. As individuals age, time often seems to accelerate. This shift may be attributed to the routine nature of daily life in adulthood and a decrease in novel experiences, leading to fewer unique memories and a compressed sense of time in retrospect (Wittmann & Lehnhoff, 2005).

5. Temporal Illusions

Our perception of time is susceptible to various illusions, where the perceived duration differs from the actual elapsed time.

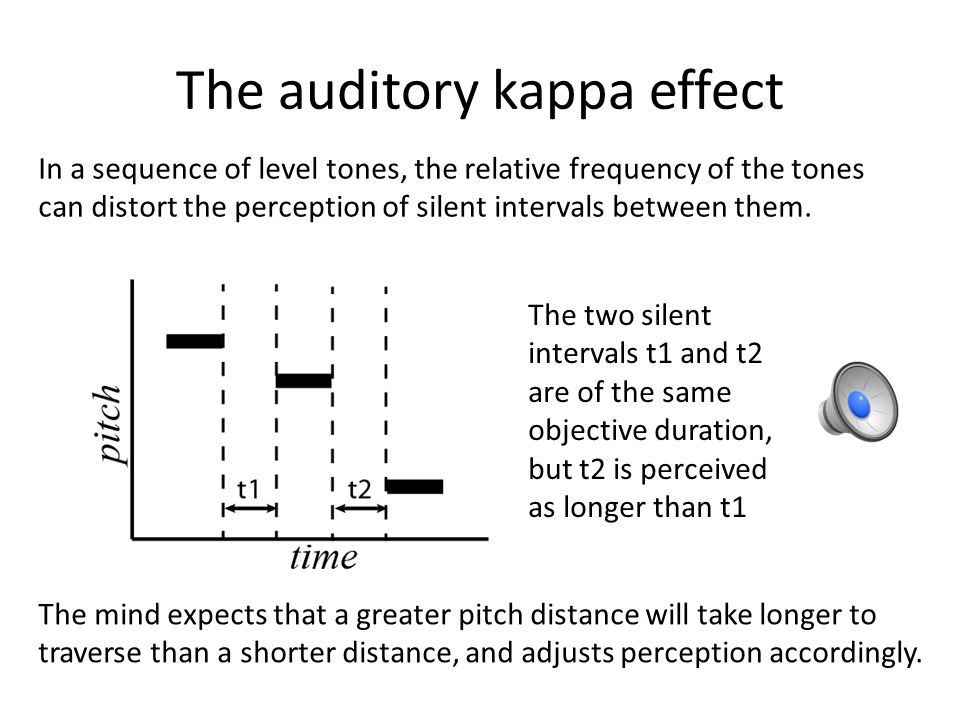

6. The Kappa Effect

The Kappa effect, or perceptual time dilation, occurs when the spatial distance between sequential stimuli influences the perceived time interval between them. For example, when observing a series of lights flashing in sequence, if the spatial distance between the lights is increased, the time interval between flashes is perceived as longer than it actually is. This illusion demonstrates the interplay between spatial and temporal processing in the brain (Jones & Huang, 1982).

7. The Tau Effect

Conversely, the Tau effect involves the perception of spatial intervals being influenced by temporal intervals. When time intervals between stimuli are varied while spatial distances remain constant, the perceived spatial distance can change. Shorter time intervals can make stimuli appear closer together in space, highlighting how temporal information can affect spatial perception (Goldreich, 2007).

Time Perception and Mental Health

Distortions in time perception are often associated with various mental health conditions. For instance, individuals with depression may experience a slowing of time, where moments seem to drag, potentially exacerbating feelings of hopelessness. Anxiety disorders, on the other hand, can lead to a heightened awareness of time, with individuals feeling that time is slipping away too quickly, contributing to increased stress and worry (Wittmann et al., 2010).

Understanding these alterations in time perception offers valuable insights into the subjective experiences of individuals with mental health disorders and can inform therapeutic approaches. Interventions that modify attention and cognitive appraisal, such as mindfulness-based therapies, may help recalibrate distorted time perceptions and improve mental well-being.

Practical Implications

Recognizing the factors that influence time perception can have practical applications in daily life.

- Enhancing Productivity- By structuring tasks to maintain engagement and introducing variety, individuals can prevent the monotony that leads to the overestimation of time and decreased productivity. Breaking tasks into manageable segments with clear goals can help maintain focus and make time seem to pass more quickly.

- Improving Well-being- Engaging in new and enriching experiences can slow down the subjective passage of time and create lasting memories. Activities such as traveling, learning new skills, or forming new social connections introduce novelty, which enhances memory encoding and expands the perception of time. Mindfulness practices that ground individuals in the present moment can also alter time perception, making experiences feel more fulfilling and less rushed (Kramer et al., 2013).

Conclusion

Time perception is a complex and dynamic construct shaped by an interplay of cognitive functions, emotional states, physiological processes, and environmental contexts. By understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying how we perceive time, we can gain deeper insights into human behavior, enhance our well-being, and develop strategies to navigate the temporal dimensions of our lives more effectively.

References

Droit-Volet, S., & Gil, S. (2009). The time–emotion paradox. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1943–1953. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0013

Goldreich, D. (2007). A Bayesian perceptual model replicates the cutaneous rabbit and other tactile spatiotemporal illusions. PLoS ONE, 2(3), e333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000333

Jones, B., & Huang, Y. L. (1982). Space-time dependencies in psychophysical judgment of extent and duration: algebraic models of time perception. Psychological Bulletin, 91(1), 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.1.128

Kramer, R. S. S., Weger, U. W., & Sharma, D. (2013). The effect of mindfulness meditation on time perception. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(3), 846-852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.05.008

Meissner, K., & Wittmann, M. (2011). Body signals, cardiac awareness, and the perception of time. Biological Psychology, 86(3), 289-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.01.001

Wittmann, M. (2009). The inner experience of time. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1955-1967. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0003

Wittmann, M., & Lehnhoff, S. (2005). Age effects in perception of time. Psychological Reports, 97(3), 921-935. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.97.3.921-935

Wittmann, M., Simmons, A. N., Aron, J. L., & Paulus, M. P. (2010). Accumulation of neural activity in the posterior insula encodes the passage of time. Biological Psychiatry, 67(8), 693-700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.003

Zakay, D., & Block, R. A. (2004). Prospective and retrospective duration judgments: An executive-control perspective. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 64(3), 319-328.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,045 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, March 2). What is Time Psychology and 7 Insightful Factors that Influence It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/time-psychology/