Introduction

Have you ever felt confident explaining how a toilet works or why the sky is blue — only to realize, under pressure, that your understanding is surprisingly shallow? This common experience captures what psychologists call the illusion of knowledge: the tendency to believe we understand more than we actually do. Despite living in an age of information, this illusion persists, shaping everything from casual conversations to public decision-making.

Understanding why this happens isn’t just intellectually interesting — it’s critical for education, policymaking, and even personal growth. The illusion of knowledge distorts judgment, stifles curiosity, and reinforces overconfidence. To see how deep this cognitive trap runs, we’ll explore its origins, psychological mechanisms, and real-world implications.

Read More: Mental Health

The Roots of the Illusion

One of the earliest insights into this phenomenon came from research on overconfidence in human judgment. Psychologists have long observed that people tend to overestimate the accuracy of their knowledge (Lichtenstein, Fischhoff, & Phillips, 1982). This effect is especially striking when individuals are asked to explain complex systems.

In a classic experiment, Rozenblit and Keil (2002) coined the term illusion of explanatory depth (IOED) to describe how people overrate their understanding of how things work. Participants in their study rated their understanding of everyday objects like zippers and toilets as high, but when asked to explain these mechanisms in detail, their confidence dropped dramatically. The realization that they didn’t truly understand the processes revealed a fundamental gap between knowing and knowing that you know.

This cognitive mismatch occurs because our brains rely heavily on heuristics and partial information. Humans evolved to use cognitive efficiency — quick judgments and surface-level comprehension that work well for survival but not for complex reasoning (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). As a result, we often mistake familiarity for mastery.

The Role of Cognitive Biases

Several well-known biases reinforce the illusion of knowledge.

-

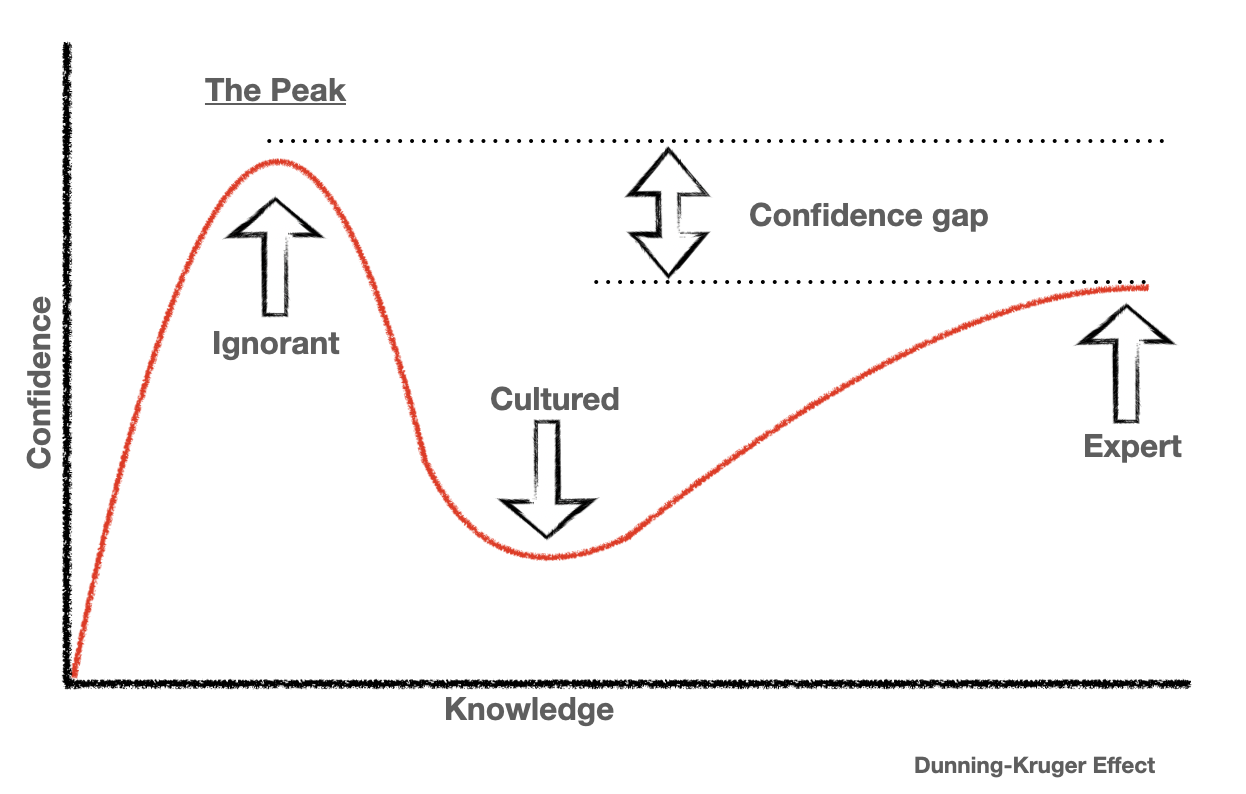

The Dunning-Kruger Effect – Perhaps the most famous, this effect shows that people with limited knowledge in a domain tend to overestimate their competence (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Ironically, the very lack of expertise prevents accurate self-assessment. The less we know, the less we realize how much we don’t know.

-

Confirmation Bias – Once we believe we understand something, we selectively notice information that supports that belief (Nickerson, 1998). This self-reinforcing loop strengthens the illusion by filtering out contradicting evidence.

-

Familiarity Bias – Repeated exposure to information, even without understanding it, increases our sense of fluency and confidence (Hasher, Goldstein, & Toppino, 1977). This explains why we might feel knowledgeable about a topic just because we’ve heard about it frequently in media.

Together, these biases create a potent psychological cocktail that fuels overconfidence.

Why the Brain Prefers “Feeling Right” Over “Being Right”

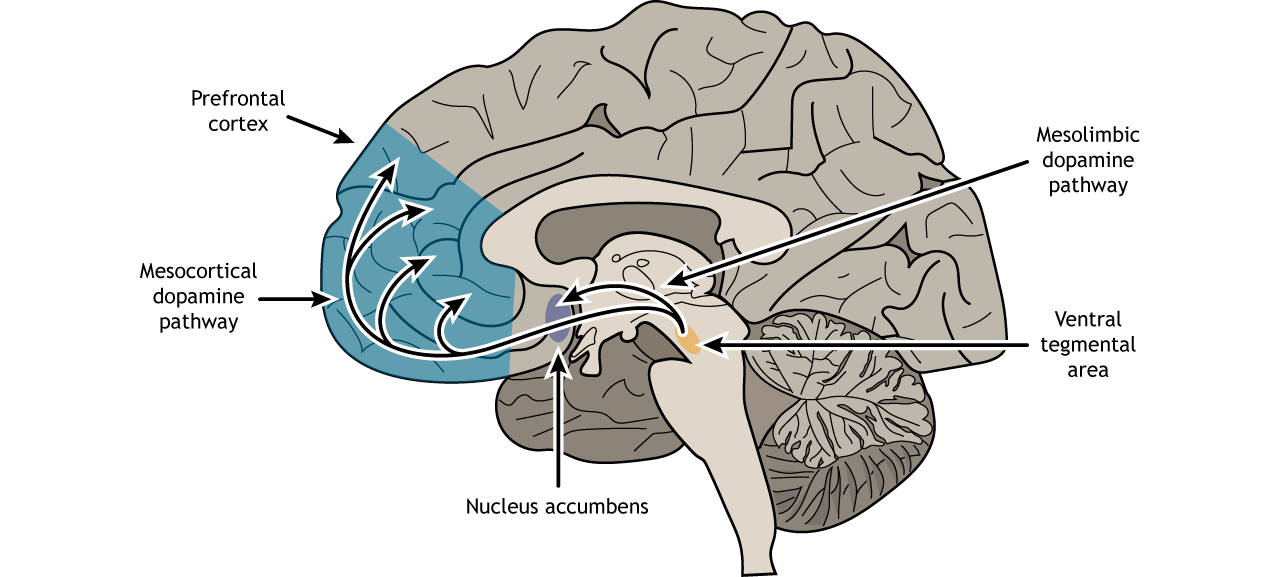

From a neurological perspective, confidence isn’t merely a byproduct of knowledge; it’s a reward mechanism. Research shows that the brain’s reward circuitry, particularly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, activates when individuals feel confident about their decisions (De Martino, Fleming, Garrett, & Dolan, 2013). This neural reinforcement makes confidence intrinsically satisfying, regardless of accuracy.

Moreover, uncertainty feels uncomfortable. Psychologists call this cognitive dissonance — the tension that arises when reality conflicts with our beliefs (Festinger, 1957). To resolve that discomfort, we often choose the emotionally easier path: maintaining the illusion of understanding rather than confronting gaps in our knowledge.

The Social Dimension of Knowledge Illusions

The illusion of knowledge isn’t just an individual quirk; it’s socially contagious. In social contexts, people tend to project confidence because uncertainty can be perceived as weakness (Sedikides & Gregg, 2008). When multiple individuals exhibit such confidence, it creates a feedback loop where the group collectively overestimates its knowledge — a phenomenon related to collective overconfidence (Pallier et al., 2002).

Social media amplifies this effect dramatically. Platforms reward strong opinions, quick takes, and confidence — not nuanced understanding. When confidence receives likes and shares, the illusion of knowledge becomes performative. People express certainty about complex issues (e.g., climate policy, public health, AI ethics) while lacking deep comprehension of the underlying science.

Educational Implications

The illusion of knowledge poses a significant challenge in education. Students who believe they understand material prematurely are less likely to study deeply or seek clarification (Dunlosky & Rawson, 2012). This overconfidence undermines learning outcomes and leads to shallow memorization rather than conceptual understanding.

Metacognition — the awareness of one’s own thought processes — is a powerful antidote. When learners engage in metacognitive reflection (e.g., self-testing, summarizing, teaching others), they are more likely to detect their knowledge gaps (Flavell, 1979; Bjork, Dunlosky, & Kornell, 2013). Educators can combat the illusion of knowledge by incorporating retrieval practice, feedback loops, and self-assessment tasks.

How to Overcome the Illusion

Some ways to overcome the illusion:

- Embrace Intellectual Humility: Recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge fosters curiosity and open-mindedness. Studies show that individuals high in intellectual humility make better judgments and are less prone to misinformation (Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, 2016).

- Practice Active Learning: Explaining concepts aloud or teaching others exposes areas of misunderstanding — a strategy known as the Feynman Technique.

- Seek Disconfirming Evidence: Intentionally look for sources that challenge your assumptions. This reduces confirmation bias and enhances comprehension.

- Slow Thinking: Daniel Kahneman (2011) distinguishes between System 1 (fast, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, analytical) thinking. Engaging the latter helps counteract automatic overconfidence.

- Metacognitive Training: Regularly asking “How do I know this?” encourages self-monitoring of knowledge accuracy.

Conclusion

The illusion of knowledge is one of the most pervasive and consequential cognitive biases in human psychology. It affects how we learn, make decisions, and interact socially. In an era where information is abundant but understanding is scarce, cultivating intellectual humility and metacognition may be among the most vital psychological skills.

True wisdom begins with acknowledging the limits of what we know — and being comfortable living in that uncertainty.

References

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444.

De Martino, B., Fleming, S. M., Garrett, N., & Dolan, R. J. (2013). Confidence in value-based choice. Nature Neuroscience, 16(1), 105–110.

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2012). Overconfidence produces underachievement: Inaccurate self-evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 271–280.

Fernbach, P. M., Rogers, T., Fox, C. R., & Sloman, S. A. (2013). Political extremism is supported by an illusion of understanding. Psychological Science, 24(6), 939–946.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911.

Hasher, L., Goldstein, D., & Toppino, T. (1977). Frequency and the conference of referential validity. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(1), 107–112.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134.

Lichtenstein, S., Fischhoff, B., & Phillips, L. D. (1982). Calibration of probabilities: The state of the art. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 306–334). Cambridge University Press.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220.

Nichols, T. (2017). The death of expertise: The campaign against established knowledge and why it matters. Oxford University Press.

Pallier, G., Wilkinson, R., Danthiir, V., Kleitman, S., Knezevic, G., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (2002). The role of individual differences in the accuracy of confidence judgments. The Journal of General Psychology, 129(3), 257–299.

Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. C. (2002). The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive Science, 26(5), 521–562.

Sedikides, C., & Gregg, A. P. (2008). Self-enhancement: Food for thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 102–116.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 3). The Illusion of Knowledge and 5 Important Ways to Overcome It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/the-illusion-of-knowledge/