Introduction

The Strong Vocational Interest Bank (SVIB) is a psychometric assessment tool widely used to measure vocational interests, aiding individuals in career guidance and development. Developed by Edward K. Strong, Jr. in the early 20th century, the SVIB has evolved into one of the most prominent interest inventories used in education, counseling, and organizational settings. This article explores the SVIB’s origins, structure, applications, and evolution, providing a nuanced understanding of its significance in vocational psychology.

Read More- Personality

Theoretical Underpinnings

The SVIB was first introduced in 1927 by Edward Kellogg Strong, Jr., a psychologist at Stanford University. Its development stemmed from the need to systematically assess individuals’ preferences for various occupational activities and environments. Influenced by career theories of John Holland and Frank Parsons, Strong aimed to create an empirical tool based on occupational satisfaction and job-fit hypotheses.

Edward K. Strong, Jr. posited that vocational interests are relatively stable over time and can predict occupational satisfaction and success. He believed that individuals’ preferences and disinterests for various activities, work environments, and tasks mirror the interests of people successfully employed in specific occupations.

His key assumptions included-

- Interests as Predictors- Strong viewed interests as reliable predictors of career success and satisfaction.

- Empirical Matching- By comparing an individual’s responses to those of people in various professions, one could identify occupational fit.

RIASEC Theory

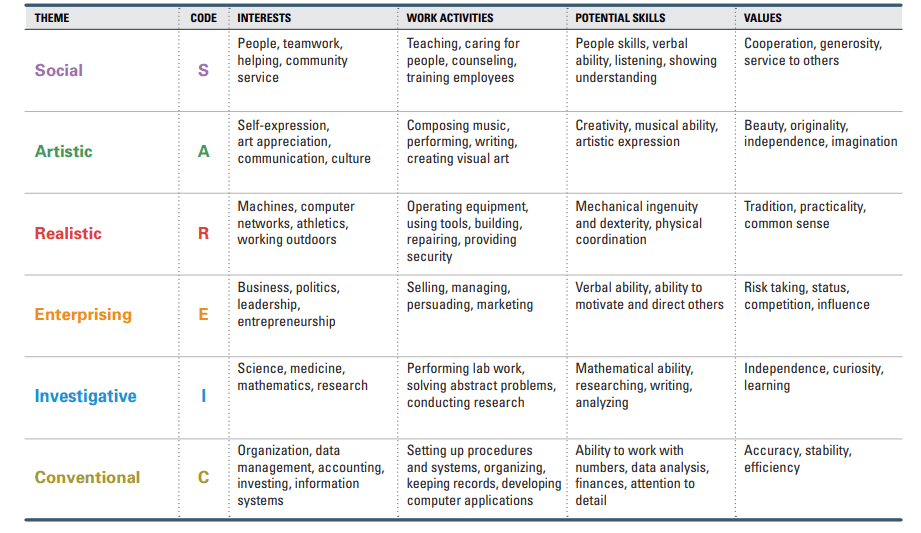

John Holland’s RIASEC theory, formally known as the Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments, is a cornerstone of vocational psychology. It provides a framework to understand how personality traits align with occupational environments.

Although Holland’s theory was formalized after the initial development of the Strong Vocational Interest Blank (SVIB), its principles have deeply influenced subsequent iterations of the SVIB, especially the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (SCII) and modern versions of the Strong Interest Inventory (SII).

Holland’s model is based on the following key assumptions:

- Personality-Environment Fit- People are more satisfied and successful in their careers when their personality traits align with the characteristics of their work environment.

- Six Personality Types- Holland identified six broad personality types, each corresponding to specific work environments. These are known as the RIASEC model (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional).

- Congruence and Vocational Satisfaction- Career satisfaction and stability are highest when there is congruence between an individual’s personality type and their vocational environment.

- Hierarchical Relationships- The RIASEC types are not independent; they are organized in a circular structure, known as the hexagonal model, which illustrates their relationships. Adjacent types (e.g., Realistic and Investigative) are more similar, while opposite types (e.g., Realistic and Social) are more dissimilar.

Each RIASEC type represents a distinct personality trait and vocational preference-

- Realistic (R)- Realistic individuals are practical, hands-on, and physically active. They prefer working with tools, machinery, and outdoor environments. Typical occupations include engineering, construction, farming, and law enforcement. Tasks they excel at include operating machinery, repairing equipment, and managing physical systems.

- Investigative (I)– Investigative personalities are analytical, intellectual, and curious. They enjoy research, scientific exploration, and problem-solving. Careers such as scientists, researchers, medical professionals, and academics suit them. Common tasks include conducting experiments, analyzing data, and formulating theories.

- Artistic (A)- Artistic individuals are creative, expressive, and imaginative. They thrive in unstructured environments that emphasize self-expression, such as writing, music, or design. They often work as artists, writers, designers, or performers, engaging in tasks like creating visual art, composing music, or writing stories.

- Social (S)- Social personalities are empathetic, cooperative, and supportive. They are drawn to roles involving helping others, such as teaching, counseling, or providing care. Common occupations include teachers, counselors, social workers, and healthcare providers. Typical tasks involve counseling individuals, teaching students, and offering support services.

- Enterprising (E)- Enterprising individuals are persuasive, ambitious, and leadership-oriented. They prefer entrepreneurial roles where they can manage people or projects. Careers such as managers, business executives, salespeople, and politicians are ideal. Key tasks include leading teams, negotiating deals, and launching initiatives.

- Conventional (C)- Conventional personalities are organized, detail-oriented, and methodical. They thrive in structured, rule-governed environments like accounting, administration, or data analysis. Typical roles include accountants, administrative assistants, and clerks, with tasks such as managing records, organizing files, and working with data.

The SVIB aligns with this theory by categorizing interests into occupational themes and linking them to personality traits.

Structure of the Strong Vocational Interest Bank (SVIB)

The SVIB is designed to compare an individual’s interests to those of people working in various occupations. Its structure involves-

- Items – Early versions contained over 400 items covering a broad range of interests, hobbies, and preferences.

- Forced-choice format: Respondents indicate their degree of interest on a Likert scale or as “Like,” “Dislike,” or “Indifferent.”

- Questions focus on topics such as:

- Work-related tasks (e.g., “Do you enjoy analyzing data?”).

- Personal interests (e.g., “Do you like creative writing?”).

- Preferences for leisure activities, leadership roles, or group collaboration.

- Time Required: 30 to 45 minutes to complete the inventory.

- Interest Areas- The inventory assesses preferences for specific activities, types of people, and work environments. It also gauges disinterest in certain occupations, providing a comprehensive profile.

- Scoring Mechanism- Scores are computed by comparing responses to normative samples of individuals in specific professions. Results are represented as interest profiles that indicate compatibility with various vocational paths.

Scales and Domains of Strong Vocational Interest Bank (SVIB)

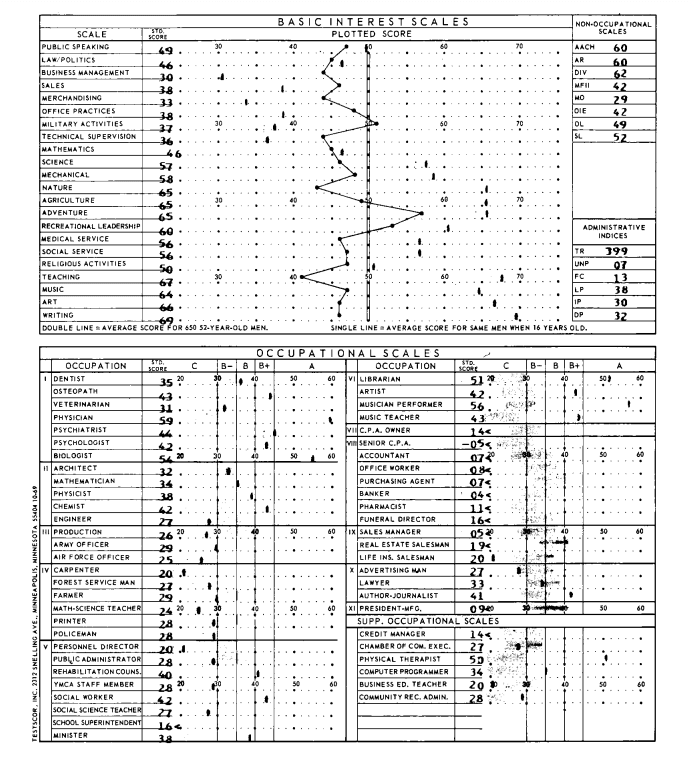

The SVIB measures multiple dimensions of interests across several scales:

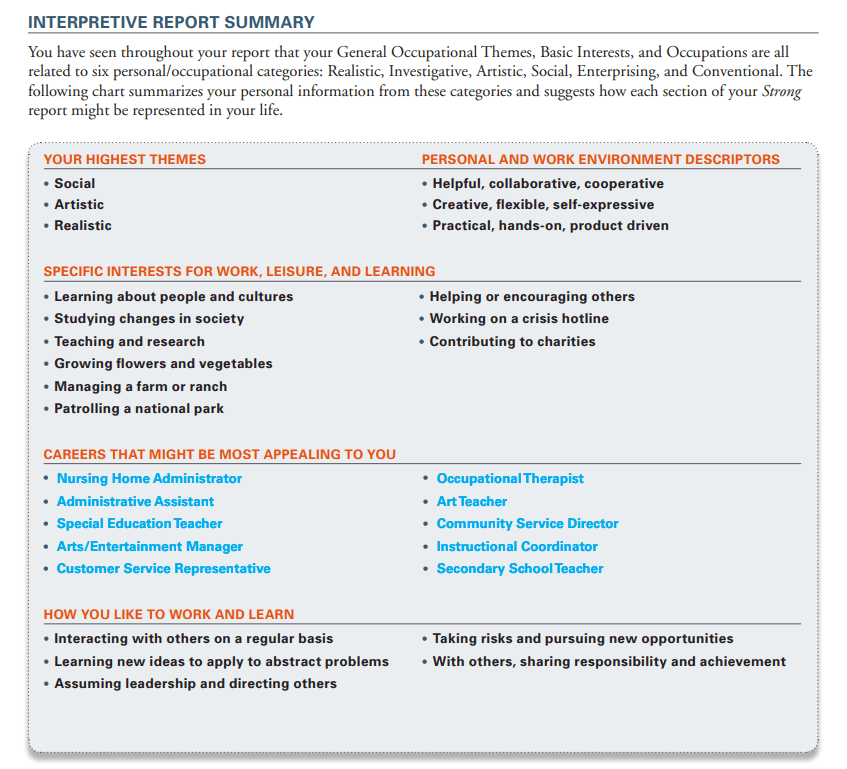

- General Occupational Themes (GOTs): Six broad categories based on Holland’s RIASEC model.

- Basic Interest Scales (BISs): Specific interests such as medicine, finance, teaching, or performing arts.

- Occupational Scales (OSs): Matches the respondent’s profile with over 130 occupations.

- Personal Style Scales: Examines preferences for learning styles, leadership, and team work.

- Administrative Indices: Validates the accuracy of responses to avoid inconsistencies

Over time, the SVIB merged with the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (SCII) to create the Strong Interest Inventory (SII), a modern adaptation.

Evolution of the Strong Vocational Interest Bank (SVIB)

The SVIB underwent significant transformations to address criticisms and adapt to changing occupational landscapes.

In the 1970s, David Campbell revised the SVIB, integrating gender-neutral scales and extending its occupational coverage. This resulted in the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (SCII), which accounted for-

-

- Shifting societal roles and opportunities for women in the workforce.

- Broader inclusion of diverse occupational interests.

The modern SII retains the SVIB’s foundational principles while incorporating advancements:

- Technology Integration- Computerized scoring and interpretation.

- Expanded Norms- Larger and more diverse sample populations to improve accuracy.

- Refined Scales- Enhanced focus on personal styles, such as risk-taking and learning preferences.

Psychometric Properties of the Strong Vocational Interest Blank

The psychometric properties of the SVIB are essential for establishing its reliability and validity.

1. Reliability- it refers to the consistency of the test results over time and across different samples. The SVIB exhibits high reliability in multiple domains-

-

- Internal Consistency- The items within each scale are highly correlated, indicating that they consistently measure similar interests. Cronbach’s alpha values for subscales typically range from 0.80 to 0.95, demonstrating strong internal reliability.

- Test-Retest Reliability- Studies show high test-retest reliability over long intervals, with coefficients often exceeding 0.85 over a span of one year and remaining above 0.70 over several years. This stability supports the idea that vocational interests are relatively enduring.

2. Validity- measures how well the SVIB assesses what it claims to measure—vocational interests. The tool demonstrates strong evidence of validity across several dimensions-

-

- Content Validity- Items were developed through extensive empirical research, comparing the interests of individuals in various professions. The inclusion of diverse occupational themes ensures comprehensive coverage of vocational interests.

- Construct Validity- Correlations with other interest inventories, such as the Kuder Occupational Interest Survey and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), support the SVIB’s construct validity. Factor analysis reveals distinct interest dimensions aligning with theoretical constructs like Holland’s RIASEC model.

- Criterion-Related Validity- Predictive validity is demonstrated by strong correlations between SVIB profiles and actual occupational choices or job satisfaction. Concurrent validity studies show that individuals employed in certain professions score higher on corresponding scales, aligning with the responses of professionals in those fields.

Read More- Mental Health and Stress

Applications of the SVIB

The SVIB serves a variety of purposes in educational, clinical, and organizational contexts-

- Career Counseling- The primary application of the SVIB is in career counseling, helping individuals- identify careers aligned with their interests, explore vocational paths based on personality traits and preferences, and make informed educational and professional decisions.

- Organizational Use- In organizations, the SVIB aids in- employee selection and placement, career development programs to enhance job satisfaction and productivity, and identification of training and development needs.

- Academic Guidance- Educational institutions utilize the SVIB to- guide students in selecting college majors and academic pathways and provide insights into students’ potential career trajectories.

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its widespread use, the SVIB has faced several criticisms-

- Cultural Bias- Early versions reflected the predominantly Western, white, male workforce of the time. Efforts to mitigate bias include updated norm groups and culturally sensitive scales.

- Predictive Validity- While the SVIB provides reliable interest profiles, its ability to predict long-term career success is debated.

- Dynamic Interests- Critics argue that interests are fluid and may change over time due to life experiences, making static assessments less effective.

- Complexity- The SVIB’s extensive item list and interpretation process can be overwhelming for some users.

Conclusion

The Strong Vocational Interest Blank (SVIB) remains a cornerstone of vocational assessment, offering invaluable insights into individuals’ career preferences. Its evolution into the Strong Interest Inventory reflects ongoing efforts to align the tool with contemporary workforce trends and diversity. While challenges persist, the SVIB’s scientific foundation and practical applications ensure its relevance in career guidance, education, and organizational development.

References

Strong, E. K. (1927). Vocational Interests of Men and Women. Stanford University Press.

Campbell, D. P. (1971). “Development of the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 1(4), 345-357.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Harmon, L. W., Hansen, J. C., Borgen, F. H., & Hammer, A. L. (1994). Strong Interest Inventory Applications and Technical Guide. Stanford University Press.

Spokane, A. R., Meir, E. I., & Catalano, M. (2000). “Person-Environment Congruence and Vocational Interest Measurement.” Journal of Career Assessment, 8(4), 352-374.

Savickas, M. L. (2013). “The Role of Career Counseling in Career Development.” Journal of Career Assessment, 21(1), 5-19.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 2,933 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, December 5). Strong Vocational Interest Bank (SVIB) and 6 Personality Traits. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/strong-vocational-interest-bank-svib/