Introduction

Self-care is often misrepresented in popular culture as indulgent pampering, like bubble baths or spa days. While relaxation is important, self-care is much more than occasional treats—it is a science-backed set of practices that maintain and enhance mental, emotional, and physical health (Schure, Christopher, & Christopher, 2008). In a fast-paced world with increasing work, school, and social pressures, neglecting self-care can contribute to chronic stress, burnout, and mental health challenges.

Read More: Mental Well-Being and Isolation

Understanding Self-Care

Self-care can be defined as any deliberate activity that individuals undertake to maintain or enhance their physical, emotional, or mental health (Orem, 2001). It encompasses:

-

Physical self-care – nutrition, exercise, sleep, and medical care.

-

Emotional self-care – processing feelings, setting boundaries, and seeking support.

-

Psychological self-care – mindfulness, cognitive strategies, and stress management.

-

Social self-care – nurturing relationships and social support.

-

Spiritual self-care – practices that foster purpose, connection, or transcendence.

Effective self-care is proactive, consistent, and tailored to individual needs rather than reactive or superficial.

The Science Behind Self-Care

Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels, immune suppression, and cardiovascular strain (McEwen, 2007). Activities such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, and aerobic exercise reduce HPA axis activation and enhance resilience to stressors (Chiesa & Serretti, 2009).

Mental Health Benefits

Regular self-care practices are associated with reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety, and burnout (Richardson et al., 2005). Self-care provides emotional regulation, enabling individuals to respond adaptively to challenges rather than react impulsively.

Cognitive and Productivity Gains

Engaging in restorative self-care improves focus, decision-making, and creativity. Neuroscience research shows that activities like exercise, meditation, and adequate sleep enhance neuroplasticity, memory consolidation, and executive functioning (Hillman, Erickson, & Kramer, 2008).

Five Proven Self-Care Practices

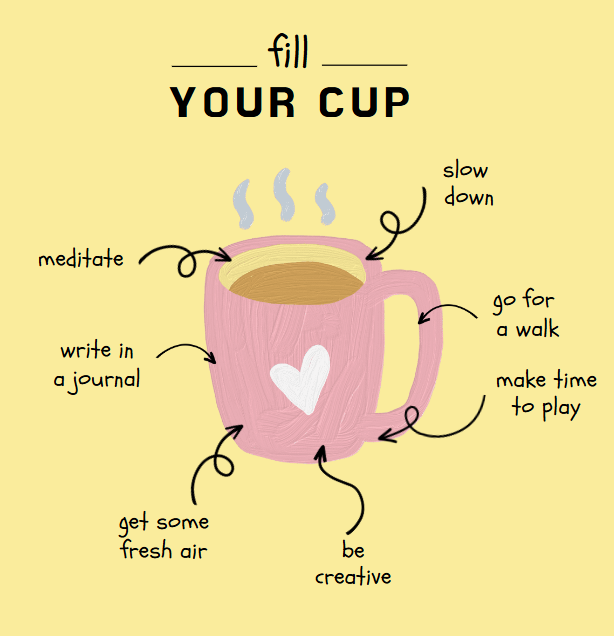

Some of the self-care practices include:

1. Prioritize Sleep

Sleep is foundational to well-being. Inadequate sleep impairs memory, attention, emotional regulation, and immune function (Walker, 2017). Sleep deprivation also heightens emotional reactivity, making stress more difficult to manage.

Practical tips:

- Maintain a consistent sleep schedule.

- Limit screen exposure 1–2 hours before bed.

- Create a relaxing bedtime routine with dim lighting and calming activities.

2. Engage in Physical Activity

Exercise is not only for fitness—it is a mental health powerhouse. Physical activity releases endorphins, reduces cortisol, and improves mood and resilience to stress (Salmon, 2001). Both aerobic exercises (running, swimming) and mind-body practices (yoga, tai chi) are effective.

Practical tips:

- Aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity weekly.

- Incorporate movement breaks during work or study sessions.

- Choose enjoyable activities to enhance adherence.

3. Practice Mindfulness and Meditation

Mindfulness involves paying attention to the present moment without judgment. Evidence shows that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) reduce stress, anxiety, and depression while improving well-being (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Practical tips:

- Start with short sessions (5–10 minutes) of guided meditation.

- Use breathing exercises to manage acute stress.

- Integrate mindful awareness into daily activities, like eating or walking.

4. Cultivate Social Connections

Humans are social beings, and social support is a critical protective factor for mental health. Strong connections buffer against stress, reduce depression, and enhance resilience (Cohen, 2004).

Practical tips:

- Schedule regular check-ins with friends and family.

- Participate in group activities or community organizations.

- Practice active listening and empathy to strengthen relationships.

5. Set Boundaries and Manage Time

Chronic overcommitment erodes well-being. Effective self-care includes recognizing limits and asserting boundaries in work, school, and personal life (Lake, 2007).

Practical tips:

- Use time-blocking techniques to protect leisure and restorative time.

- Learn to say no without guilt.

- Reduce multitasking to improve focus and reduce cognitive overload.

Common Misconceptions About Self-Care

-

Self-care is selfish – In reality, self-care enables individuals to function optimally and support others effectively.

-

Self-care is expensive – Many evidence-based practices, such as sleep, exercise, and mindfulness, are low-cost or free.

-

Self-care requires hours of time – Even brief, consistent practices (e.g., 10 minutes of meditation) provide measurable benefits.

-

Self-care is indulgent – True self-care focuses on sustainability and health, not temporary pleasure.

Integrating Self-Care Into Daily Life

Consistency is key. Self-care should be approached as a lifestyle rather than an occasional treat. Practical strategies include:

- Morning or evening routines that incorporate mindfulness or reflection.

- Scheduled breaks during work or study sessions.

- Digital detox periods to reduce cognitive and emotional overload.

- Self-reflection exercises such as journaling to monitor mental health.

Research shows that even small daily interventions accumulate to significant long-term improvements in well-being (Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005).

The Role of Organizations in Promoting Self-Care

Schools, workplaces, and community organizations play a crucial role in supporting self-care. Policies that promote work-life balance, flexible scheduling, mental health days, and wellness programs increase engagement and reduce burnout. For students, curricula incorporating social-emotional learning (SEL) foster habits of self-care and resilience from a young age.

Conclusion

Self-care is far more than bubble baths or indulgence—it is a critical, science-backed practice that protects mental, emotional, and physical well-being. By prioritizing sleep, engaging in physical activity, practicing mindfulness, cultivating social connections, and setting healthy boundaries, individuals can strengthen resilience, reduce stress, and improve quality of life.

Effective self-care requires intentionality, consistency, and integration into daily routines. When individuals commit to self-care, they are not only improving their own health but also enhancing their capacity to thrive in relationships, education, and work environments.

In an increasingly fast-paced world, self-care is not a luxury—it is a proven necessity for sustainable mental health and well-being.

References

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(5), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0495

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

Hillman, C. H., Erickson, K. I., & Kramer, A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2298

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg016

Lake, R. (2007). Setting boundaries as self-care: Balancing obligations and personal health. Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650530601102241

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

Orem, D. E. (2001). Nursing: Concepts of practice (6th ed.). Mosby.

Richardson, K., et al. (2005). Self-care in mental health: Empirical evidence and practical guidelines. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(3), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00839.x

Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00032-X

Schure, M. B., Christopher, J., & Christopher, S. (2008). Mind–body medicine and the art of self-care: Teaching mindfulness to counseling students through yoga, meditation, and journaling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00440.x

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 10). Self-Care and 5 Proven Practices for Effective Mental Health. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/self-care/