Introduction

It’s 2 a.m., and your mind is still replaying that awkward conversation from earlier. You know it’s pointless, but your brain refuses to stop spinning. This cycle of relentless thought, often called overthinking or rumination, is a mental trap that countless people experience. It’s not just a bad habit—it’s a deeply ingrained psychological pattern tied to how the human brain processes uncertainty, emotion, and self-awareness.

In psychology, overthinking is often defined as the repetitive focus on one’s distress, concerns, or perceived mistakes without moving toward problem-solving (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). While reflection can be healthy, overthinking becomes harmful when it turns into circular worry that amplifies anxiety, drains motivation, and interferes with sleep and relationships.

Let’s unpack what science says about why we overthink—and how to stop it.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

The Roots of Overthinking: Evolution and Emotion

Overthinking might feel like a flaw, but it evolved for a reason. Early humans who anticipated potential threats—like predators or food shortages—were more likely to survive. This ancient vigilance still operates today, but instead of scanning for lions, we obsess over emails, social cues, or what our boss really meant.

Psychologists suggest that overthinking stems from the same neural systems that support planning and learning (Borkovec et al., 2004). The default mode network (DMN)—a set of interconnected brain regions active during rest and self-referential thought—is especially implicated (Raichle et al., 2001). When this network overactivates, the mind wanders excessively, replaying past events or imagining worst-case scenarios.

Moreover, emotion plays a central role. According to Susan Nolen-Hoeksema’s (2000) response styles theory, rumination arises as a maladaptive way to manage sadness or anxiety. Instead of confronting or resolving emotions, we analyze them endlessly, mistakenly believing insight will come from more thought. Paradoxically, this only prolongs distress.

The Cognitive Mechanics of Overthinking

At its core, overthinking is fueled by three psychological processes:

-

Intolerance of Uncertainty – People who struggle to accept ambiguity often replay scenarios in hopes of finding certainty (Dugas & Koerner, 2005). Yet certainty never arrives, perpetuating the mental loop.

-

Metacognitive Beliefs – According to Wells’ (2009) metacognitive model, individuals hold beliefs about thinking itself—for example, “If I worry enough, I’ll prevent bad things from happening.” These beliefs reinforce rumination as a perceived coping strategy.

-

Cognitive Biases – Overthinkers are prone to biases like catastrophizing (expecting the worst) and confirmation bias (seeking evidence that supports their fears). These distortions make overthinking feel logical even when it’s not.

In neuropsychological terms, overthinking reflects a tug-of-war between the prefrontal cortex (responsible for reasoning and control) and the amygdala (the emotional alarm system). When anxiety hijacks the amygdala, rational thought weakens, and the brain spirals into repetitive analysis (Etkin et al., 2015).

The Emotional Cost

Overthinking doesn’t just drain mental energy—it contributes to serious psychological conditions. Studies consistently link rumination with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and insomnia (Watkins, 2008; Thomsen, 2006).

In depression, rumination intensifies negative mood and delays recovery by focusing attention on problems instead of solutions (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). For those with anxiety, the mind’s constant vigilance creates an illusion of control, even though it fuels more worry.

Prolonged overthinking can also lead to emotional burnout. The brain, much like a muscle, tires from excessive cognitive load. When mental energy depletes, decision-making falters, and even minor choices feel overwhelming—a state psychologists call decision fatigue (Baumeister et al., 1998).

Perfectionism and the Fear of Failure

One of the strongest drivers of overthinking is perfectionism. Perfectionists set unrealistically high standards and are hyperaware of mistakes, leading to constant self-criticism (Flett & Hewitt, 2002). This mindset fosters a chronic loop of analysis—“What if I mess up?” “What will they think?”—that paralyzes action.

Social comparison intensifies this effect. In a culture obsessed with performance and productivity, many people internalize the belief that mistakes equal inadequacy. This fear of imperfection activates overthinking as a misguided attempt to “get it right” before taking risks.

The Physiology of a Racing Mind

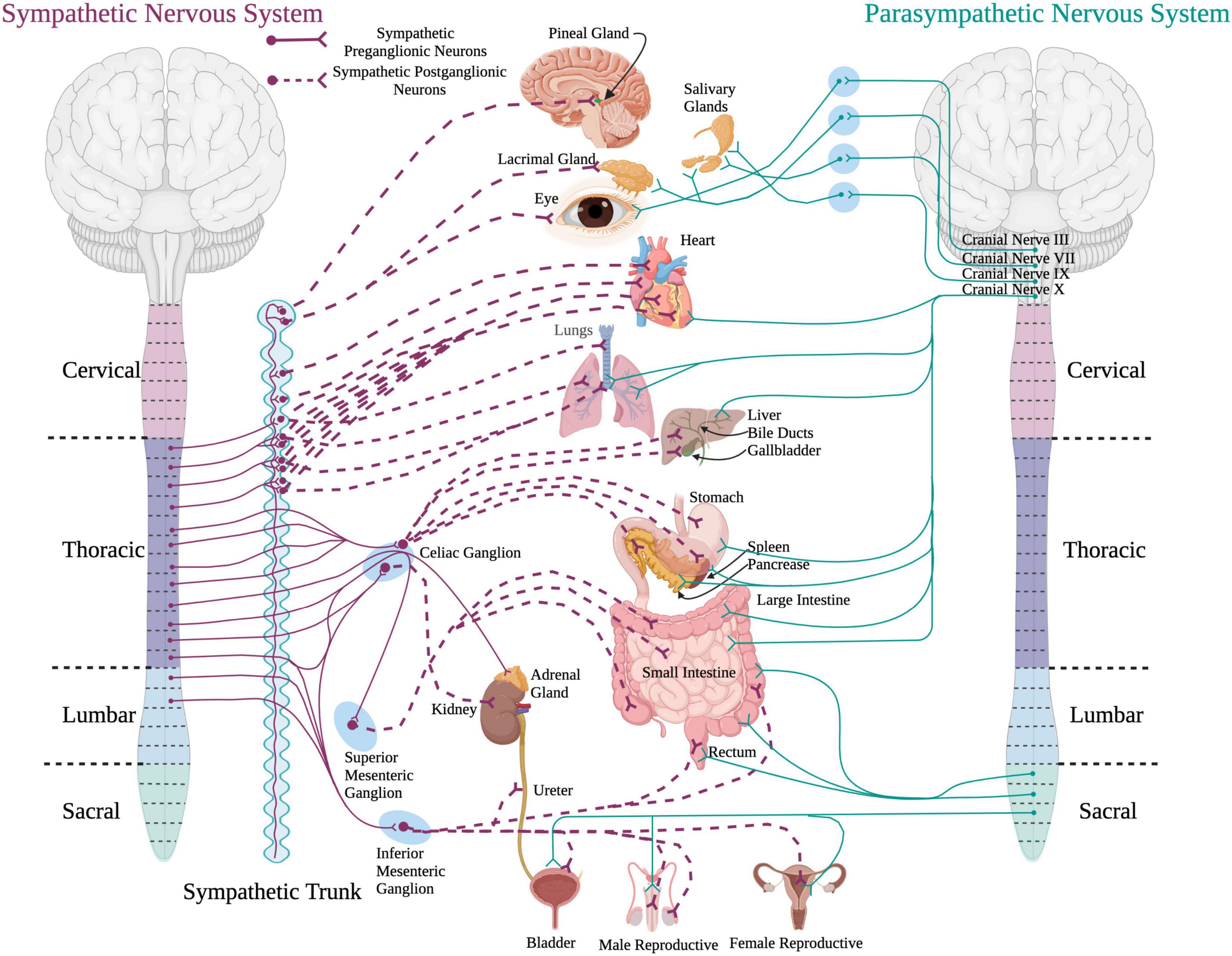

Overthinking isn’t just psychological—it’s physical. Chronic rumination keeps the sympathetic nervous system activated, flooding the body with stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline (McEwen, 2007). This “fight or flight” state increases heart rate, tenses muscles, and disrupts digestion and sleep.

Neuroscientific studies reveal that people prone to overthinking show heightened activity in the medial prefrontal cortex—an area linked to self-referential thought—and reduced connectivity with the regions that regulate emotional control (Hamilton et al., 2011). This neural imbalance traps individuals in cycles of self-focus and worry.

Breaking the Cycle

Overthinking thrives on unawareness. The more we feed it with attention, the stronger it grows. Research-backed techniques can help disrupt the cycle and restore calm.

1. Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness trains attention to remain in the present moment, reducing automatic rumination (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). MRI studies show that regular mindfulness practice decreases DMN activity, lowering the tendency for intrusive thought (Brewer et al., 2011).

2. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT teaches individuals to identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns. Techniques like thought records and cognitive restructuring help replace catastrophic thinking with balanced reasoning (Beck, 2011).

3. Metacognitive Therapy (MCT)

Developed by Adrian Wells, MCT specifically targets the beliefs that sustain overthinking. By questioning ideas like “Worrying helps me prepare,” individuals learn to detach from thoughts rather than suppress them (Wells, 2009).

4. Behavioral Activation

Instead of endlessly analyzing, act. Taking small steps toward goals interrupts rumination and reinforces a sense of agency. Research shows that engaging in meaningful activity reduces depressive rumination (Martell et al., 2010).

5. Physical Exercise

Regular movement lowers stress hormones and increases endorphins, promoting relaxation and improving cognitive flexibility (Ratey, 2008). Even a 10-minute walk can disrupt overthinking spirals.

The Paradox of Letting Go

One of the hardest lessons about overthinking is that control often requires surrender. The more we try to force thoughts away, the louder they return. Psychologists call this the ironic process—when efforts to suppress thoughts make them rebound stronger (Wegner, 1994).

The antidote isn’t suppression but acceptance. Practices like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) teach people to observe thoughts without judgment, reducing their emotional grip (Hayes et al., 2012). Over time, this fosters cognitive flexibility—the ability to shift attention away from worry toward purposeful action.

The Digital Mind

In today’s hyperconnected world, overthinking finds fertile ground. Constant notifications, social comparisons, and information overload overstimulate the brain’s threat system. The endless scroll of news and social media keeps us analyzing, comparing, and second-guessing.

Psychologists call this cognitive noise—the clutter of unfinished thoughts and micro-stresses that deplete mental bandwidth (Mark et al., 2016). Digital minimalism, setting boundaries around screen time, and embracing “offline moments” can help quiet the noise and restore focus.

Thinking Less, Living More

Overthinking often masquerades as intelligence or conscientiousness. But true insight comes not from endless analysis, but from awareness, balance, and action. As the poet Rumi wrote, “Why do you stay in prison when the door is so wide open?”

Learning to think less doesn’t mean caring less—it means trusting more: trusting your instincts, your ability to adapt, and the imperfection of life itself.

The goal isn’t to silence your thoughts, but to change your relationship with them. When you learn to observe without obsession, your mind becomes a tool—not a tormentor.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O. M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. Guilford Press.

Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y.‐Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20254–20259.

Dugas, M. J., & Koerner, N. (2005). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Current status and future directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19(1), 61–81.

Etkin, A., Büchel, C., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(11), 693–700.

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism and maladjustment: An overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 5–31). American Psychological Association.

Hamilton, J. P., Farmer, M., Fogelman, P., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Depressive rumination, the default-mode network, and the dark matter of clinical neuroscience. Biological Psychiatry, 70(4), 327–333.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2016). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Human Factors, 53(3), 560–567.

Martell, C. R., Dimidjian, S., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424.

Raichle, M. E., et al. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676–682.

Ratey, J. J. (2008). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. Little, Brown Spark.

Thomsen, D. K. (2006). The association between rumination and negative affect: A review. Cognition and Emotion, 20(8), 1216–1235.

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206.

Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101(1), 34–52.

Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 10). The Science of Overthinking and 3 Important Cognitive Mechanisms of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/science-of-overthinking/