Introduction

Repetition is a fundamental aspect of human psychology. It governs how we learn, form habits, retain memories, and make decisions. From daily rituals like brushing teeth to complex skills like playing an instrument, repetition molds our cognitive and behavioral patterns. Yet repetition can also bring monotony, stagnation, and mental fatigue. The psychological relationship with repetition is thus paradoxical: it is both the engine of mastery and the root of boredom. This article explores the dual nature of repetition, examining how it shapes identity, memory, motivation, and emotional well-being.

Read More- Sleep and Mental Health

The Cognitive Science Behind Repetition

Repetition is the key to neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to change and adapt over time. Hebbian theory encapsulates this with the phrase “neurons that fire together wire together” (Fields, 2005). This principle explains how repetitive behaviors strengthen synaptic connections, solidifying new learning and behavioral patterns.

Procedural memory, the memory of how to perform tasks, relies heavily on repetition. Activities like riding a bike, typing, or cooking become effortless through repeated practice. Graybiel (2008) emphasized that the basal ganglia play a crucial role in this process, storing repeated actions into automatic routines.

Additionally, repetition fosters cognitive fluency, making information easier to process. This phenomenon, often exploited in advertising and education, leads individuals to perceive repeated messages as more truthful—a bias known as the “illusory truth effect” (Fazio et al., 2015).

Habit Formation and Behavioral Repetition

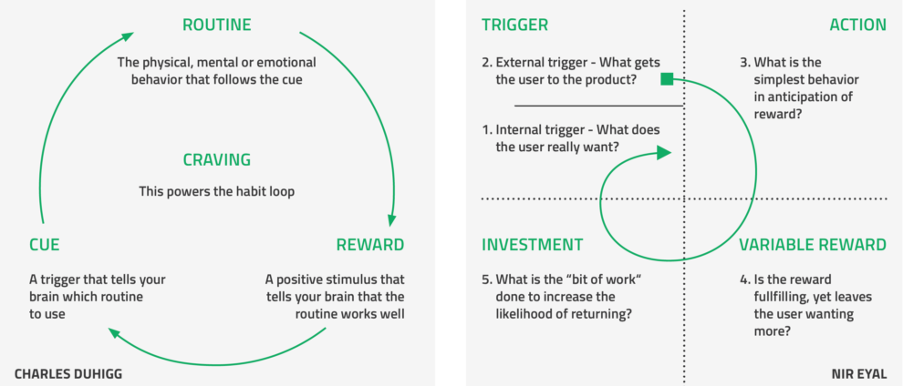

According to Duhigg (2012), habits are formed through a neurological loop: cue, routine, and reward. When behaviors are repeated in response to consistent cues, the brain begins to automate the process. Eventually, the behavior becomes habitual, reducing the need for conscious thought and freeing up cognitive resources for other tasks.

Repetition in habit formation is not only efficient but also emotionally comforting. Predictable routines create a sense of stability and control, especially in times of uncertainty. They provide structure and reduce the mental load associated with constant decision-making.

However, habits formed through repetition can be both constructive (e.g., regular exercise) or detrimental (e.g., compulsive checking of smartphones). The content of the repetition—what is repeated—matters just as much as the act of repeating.

The Psychological Cost of Monotony

Despite its cognitive benefits, excessive repetition can lead to hedonic adaptation. Brickman and Campbell (1971) describe this as the tendency to return to a baseline level of happiness despite repeated exposure to pleasurable stimuli. This explains why exciting routines, once novel, may become dull and emotionally flat over time.

Overexposure to the same tasks or environments can also result in mental fatigue, lowered motivation, and decreased engagement. This is particularly evident in workplace settings, where repetitive tasks without variation are linked to burnout and reduced job satisfaction (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

Another related concept is the “overlearning effect,” which occurs when continued practice after mastery does not yield significant benefits and can even cause diminished attention and interest (Driskell et al., 1992). Repetition without purpose can hinder rather than help.

Repetition in Memory and Learning

In education, spaced repetition is a widely researched and effective learning strategy. Unlike cramming, spaced repetition involves reviewing information at increasing intervals, enhancing long-term memory retention (Cepeda et al., 2006).

However, not all repetition leads to effective learning. Mere repetition without understanding—known as rote memorization—may lead to shallow processing. Deeper learning occurs when repetition is combined with elaboration, reflection, and contextualization (Craik & Tulving, 1975).

Repetition also plays a role in trauma and anxiety disorders. Re-experiencing intrusive memories, as seen in PTSD, involves the involuntary repetition of distressing events. Here, repetition becomes maladaptive, reinforcing fear responses rather than resolving them (van der Kolk, 2014).

Emotional and Social Aspects of Routine

Routines, built on repetition, contribute to a sense of identity. Rituals—be they personal, cultural, or religious—anchor individuals within communities and provide meaning. For instance, morning routines can signal the start of a productive day, while family dinners may reinforce social bonds.

However, societal repetition—such as rigid schedules or systemic inequalities—can create feelings of entrapment or hopelessness. The challenge lies in distinguishing between healthy structure and psychological rigidity. Flexibility within routines often yields better mental health outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted both sides of repetition. As people were confined to repetitive routines, many experienced mental stagnation. Simultaneously, those routines offered comfort and predictability amidst chaos (Killgore et al., 2020).

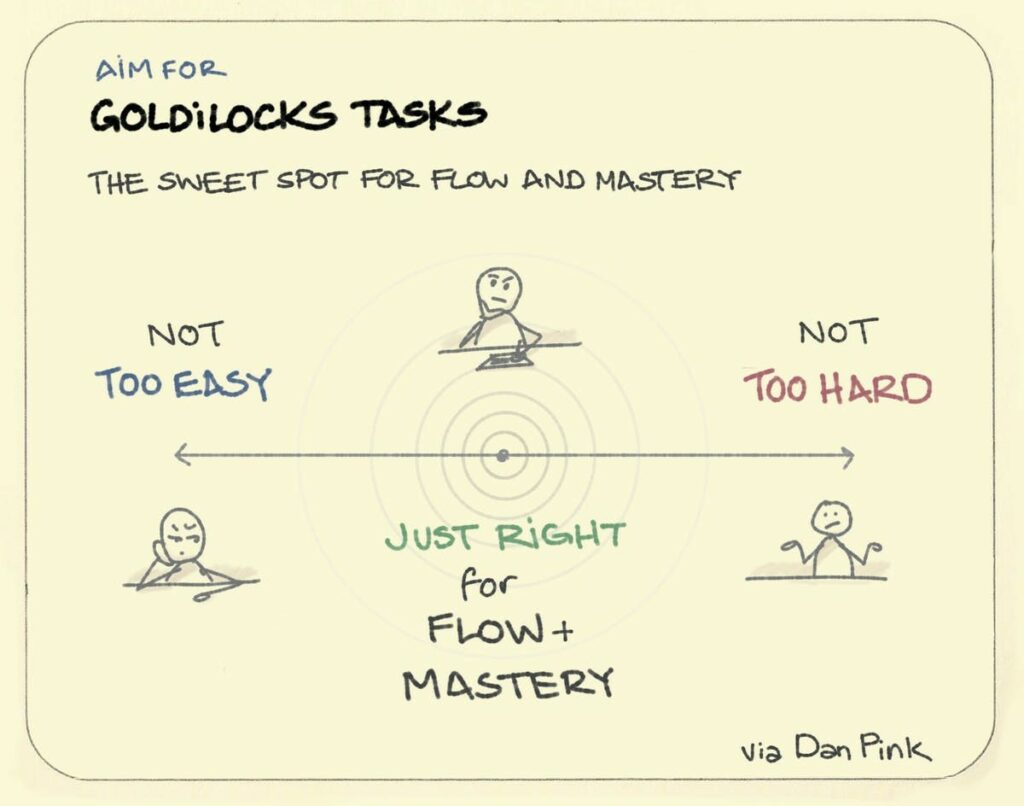

Creativity and the Goldilocks Principle

Humans seek novelty, but not too much. The “Goldilocks Principle” suggests that optimal learning and engagement occur when stimuli are neither too familiar nor too novel—just right (Kidd et al., 2012). Balancing repetition with variety enhances creativity and prevents mental stagnation.

Creative disciplines like music, writing, and art rely on repetitive practice to build skill, but also require periodic novelty to sustain motivation. This is reflected in the concept of “deliberate practice,” where individuals intentionally vary their routine to stretch their abilities (Ericsson et al., 1993).

Managing Repetition for Psychological Health

To leverage the benefits of repetition while avoiding its pitfalls, psychologists suggest:

- Habit stacking: Pairing new behaviors with existing routines to reinforce positive change (Clear, 2018).

- Routine auditing: Periodically assessing one’s schedule for alignment with current goals.

- Micro-novelty: Introducing small changes into routines to maintain interest and motivation.

- Mindful repetition: Engaging fully in repeated tasks, such as in mindful walking or meditation.

In clinical settings, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) often employs repetition through homework assignments and thought journaling to rewire dysfunctional thought patterns. Repetition here is purposeful and adaptive.

Conclusion

Repetition is the engine behind habit, memory, skill, and identity. It offers cognitive efficiency, emotional stability, and a framework for personal growth. Yet unchecked repetition can erode novelty, dampen joy, and lead to psychological stagnation. The key lies in balance—recognizing when routine serves us and when it restrains us.

By understanding the psychological mechanisms behind repetition, individuals can design lives that are both structured and stimulating, repetitive yet rich in meaning. Routine, when paired with purpose and variation, becomes not a cage, but a canvas.

References

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level theory (pp. 287–302). Academic Press.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380.

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Avery.

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 268–294.

Driskell, J. E., Willis, R. P., & Copper, C. (1992). Effect of overlearning on retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(5), 615–622.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. Random House.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N. M., Payne, B. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2015). Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(5), 993–1002.

Fields, R. D. (2005). Making memories stick. Scientific American, 292(2), 74–81.

Graybiel, A. M. (2008). Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, 359–387.

Kidd, C., Piantadosi, S. T., & Aslin, R. N. (2012). The Goldilocks effect: Human infants allocate attention to “just right” complexity. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e36399.

Killgore, W. D., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., Miller, M. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113392.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 19). Science Behind Repetition and 4 Important Ways to Harness It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/science-behind-repetition/