Introduction

Imagine walking into a party and finding a single potato chip on the snack table. Suddenly, that chip is no longer a salty afterthought—it’s the most desirable food in the room. You hover, eye twitching, convinced someone else will swoop in and snatch it. What just happened? You’ve entered the psychological world of scarcity, where lack—whether real or imagined—makes something feel overwhelmingly urgent.

Read More: Forming Good Habits

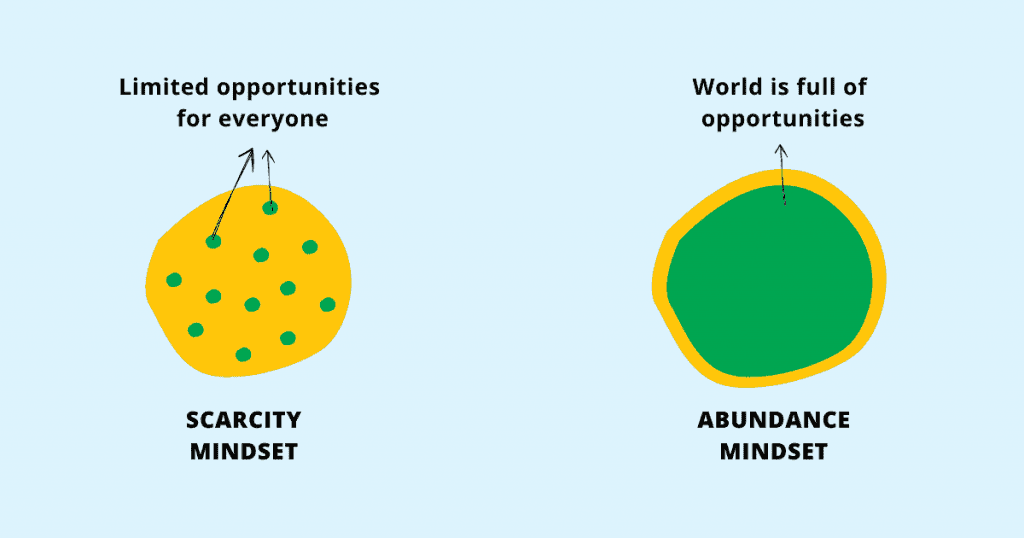

This isn’t just about chips. It’s about how the scarcity mindset shapes financial choices, life decisions, and even empathy for others. When our minds are trapped in the cycle of “not enough,” our ability to think clearly, plan effectively, and connect emotionally shrinks. The good news? By understanding how scarcity works, we can loosen its grip.

Defining the Scarcity Mindset

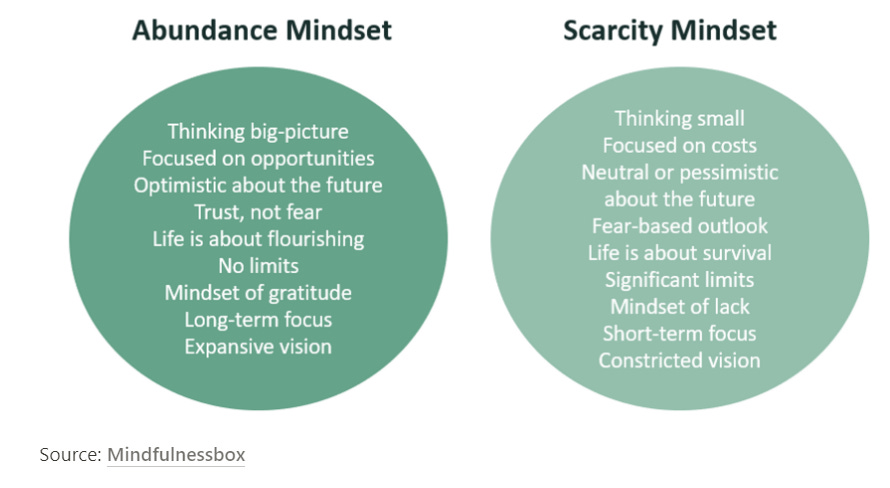

The scarcity mindset is the pervasive belief that resources—money, time, opportunities—are always insufficient (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). It is not merely an economic condition; it is a psychological one. People living with actual deprivation certainly feel it, but so do many with stable incomes and secure lives. It manifests in behaviors such as hoarding, overanalyzing decisions, or neglecting long-term goals because immediate needs dominate attention (Shah, Mullainathan, & Shafir, 2012).

In essence, scarcity is less about what you have and more about how you think about what you have. A millionaire convinced that they lack enough wealth may feel as deprived as someone worried about their next paycheck.

The Neuroscience of Scarcity

Scarcity doesn’t just alter mood—it restructures cognition. Research using functional neuroimaging shows that when people experience scarcity, activity in the prefrontal cortex, which governs planning and self-control, decreases, while brain regions tied to immediate reward heighten in response (Huijsmans et al., 2019).

This neural tradeoff means that scarcity narrows attention to the most pressing concern—a phenomenon known as tunneling. While helpful in survival situations (e.g., focusing on finding food), tunneling comes at a cost: other important but less urgent priorities fall away. For someone stressed about money, this may mean ignoring medical checkups, skipping bills, or abandoning professional development.

Scarcity and Cognitive Load

Scarcity creates a heavy cognitive load—the mental effort consumed by persistent worry. Shah et al. (2012) demonstrated that when people were primed to think about financial scarcity, their performance on unrelated cognitive tasks dropped significantly. Essentially, scarcity hijacks mental bandwidth, leaving fewer resources for rational thought.

This explains why individuals under financial stress may make impulsive or seemingly irrational decisions, such as borrowing at high interest rates or avoiding planning altogether. These choices are not signs of weakness; they are predictable consequences of a brain overtaxed by scarcity.

Present Bias

Scarcity amplifies present bias, the tendency to prioritize immediate rewards over future benefits (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014). When money feels scarce, saving for retirement pales in importance compared to paying this month’s rent. Even small windfalls are treated differently. For example, people experiencing scarcity are more likely to spend unexpected money on necessities rather than on pleasure, even when their basic needs are already met (Cheng, Duan, & Zhu, 2023).

While this behavior can appear prudent, it undermines long-term financial health. By repeatedly choosing short-term relief, individuals reduce their ability to escape cycles of scarcity.

Scarcity and Empathy

Scarcity not only affects individual decision-making but also interpersonal relationships. Li et al. (2023) found that individuals primed with scarcity mindsets exhibited reduced empathic responses to others’ pain. When resources feel limited, the capacity to care for others diminishes, as self-preservation dominates. This may explain why environments of scarcity can foster social fragmentation, mistrust, or even hostility.

Financial Behaviors Shaped by Scarcity

The scarcity mindset warps financial behaviors in several ways:

-

Over-Saving or Hoarding: Even when financially secure, individuals may hoard resources, fearing imagined future shortages.

-

Risk Avoidance: Scarcity increases anxiety, making people avoid investment or career risks that could generate long-term growth (Mani et al., 2013).

-

Impulse Spending: For others, scarcity manifests in “treat yourself” behaviors, where immediate gratification provides temporary relief from deprivation.

-

Debt Cycles: Payday loans or high-interest borrowing offer short-term fixes but perpetuate scarcity in the long run.

All these behaviors are consistent with a mind overwhelmed by short-term survival, unable to step back for long-term strategy.

Time, Love, and Opportunity

Though financial scarcity is the most studied, the mindset applies broadly. Time scarcity—the feeling of never having enough hours—can leave people harried, distracted, and less generous with others (Zhu & Ratner, 2015). Emotional scarcity, such as fearing there is not enough love or attention, may lead to jealousy or overdependence in relationships. In each case, the scarcity mindset narrows focus and reduces flexibility.

Strategies to Counter Scarcity

Fortunately, scarcity is not destiny. Researchers and practitioners suggest several strategies to weaken its hold:

-

Awareness and Labeling: Simply recognizing scarcity thoughts (“I’ll never have enough”) can help detach from them (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013).

-

Gratitude Practices: Focusing on abundance, however small, counteracts the mental tunnel (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). Writing daily gratitude notes has been shown to improve optimism and reduce stress.

-

Micro-Goals: Small, achievable steps—saving a modest amount weekly or completing a minor task—restore a sense of control and progress (Duckworth et al., 2011).

-

Structured Decision-Making: Using rules, checklists, or automatic transfers reduces cognitive load by removing decision friction.

-

Allowing Joyful Spending: Allocating even a small portion of money for pleasure helps disrupt the cycle of constant deprivation and reminds the brain that life is more than survival.

From Scarcity to Abundance

Escaping the scarcity mindset isn’t simply about better financial outcomes—it improves overall well-being. People who adopt abundance-oriented thinking report:

-

Improved decision-making: More attention to long-term consequences.

-

Greater empathy: More emotional bandwidth to connect with others.

-

Reduced stress: Lower cognitive load frees mental resources.

-

Higher resilience: The ability to see beyond immediate obstacles creates flexibility and adaptability.

In short, shifting from scarcity to abundance transforms not just the wallet, but the heart and mind.

Conclusion

Scarcity convinces us we are always one step away from disaster, whether about money, time, or love. But understanding how scarcity hijacks cognition allows us to reclaim control. Through awareness, gratitude, and intentional practices, we can loosen its grip. Life, after all, is not one lonely chip at the party—it’s a table full of possibilities, if we can only see beyond the tunnel.

References

Cheng, L., Duan, J., & Zhu, X. (2023). Influences of mental accounting on consumption decisions: The moderating role of scarcity mindset. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1162916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1162916

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2011). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2014). On the psychology of poverty. Science, 344(6186), 862–867. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1232491

Huijsmans, I., Ma, I., Micheli, L., Civai, C., Stallen, M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2019). A scarcity mindset alters neural processing underlying goal-directed decision-making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(24), 11515–11520. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818572116

Li, W., Liu, P., Li, X., & Chen, Q. (2023). Scarcity mindset reduces empathic responses to others’ pain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 18(3), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsac082

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Times Books.

Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science, 338(6107), 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222426

Zhu, M., & Ratner, R. K. (2015). Scarcity mindset and sharing. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv004

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 15). The Scarcity Mindset’s Sneaky Influence and 5 Important Ways to Break From It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/scarcity-mindset/

Pingback: URL