When Oxford University Press announced “ragebait” as its 2025 Word of the Year, it felt less like a celebration of language and more like a diagnosis. Suddenly, a term that once floated around niche media-criticism circles became an official entry in the cultural vocabulary. Oxford described it as online content engineered to provoke anger—material crafted so that we react instinctively, type furiously, and share impulsively.

But why has ragebait become not just a word, but the word of the year?

Because the digital environment we live in is perfectly calibrated for it. Platforms compete for attention; creators compete for engagement; and our psychology, predictably and reliably, responds more strongly to outrage than to almost anything else.

Understanding ragebait, then, isn’t just about media literacy. It’s about understanding how the human mind works, and how those mechanisms are being mined at scale.

Read More: Media and War Coverage

Why This Word, Right Now?

Linguists often say that a word becomes central not when it emerges, but when society decides it finally needs a name for something it can no longer ignore. The sudden elevation of “ragebait” reflects our collective exhaustion with digital hostility and performative anger.

More importantly, naming the phenomenon allows us to see it. And once we see it, we can question it.

Language is a lens—and Oxford’s selection brings a blurry problem into sharper psychological focus.

The Psychology of Why Ragebait Works

Ragebait is not effective because people are irrational or overly emotional; it works because it exploits robust, well-documented features of human cognition and social behavior.

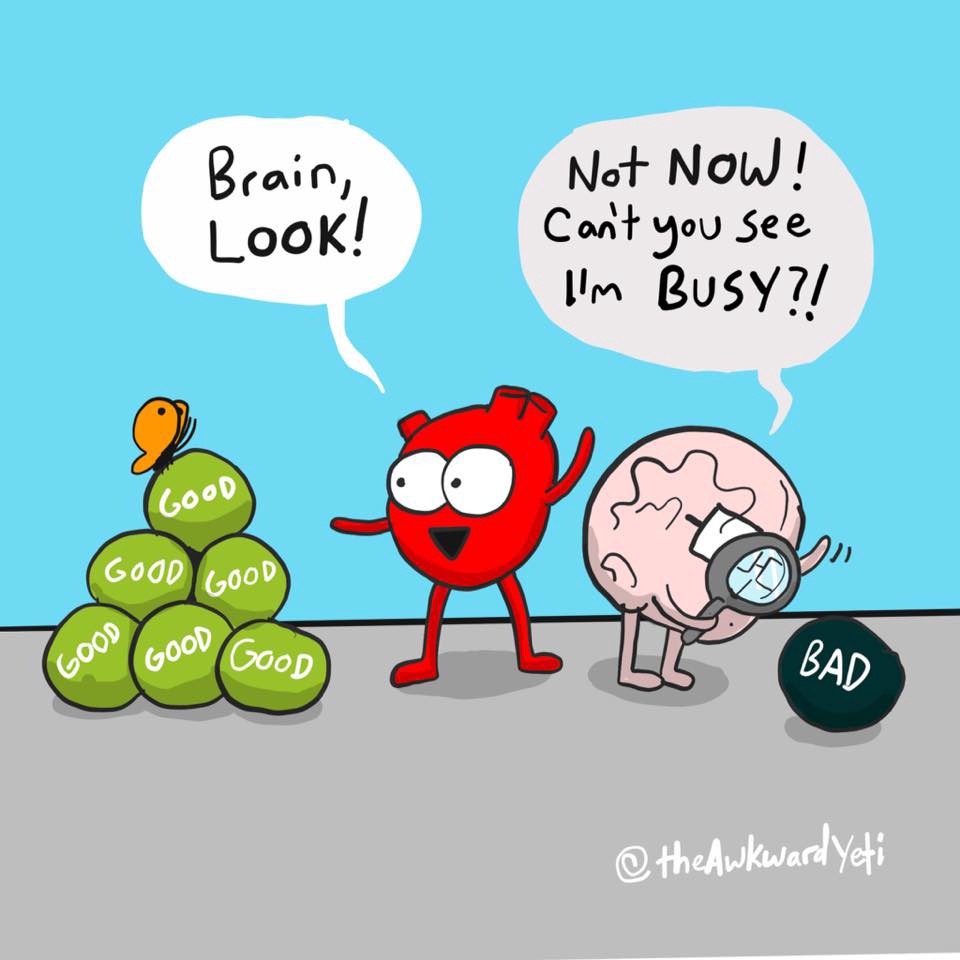

1. Negativity Bias

Humans attend to negative information more quickly and hold on to it more tightly than positive information. This “negativity bias” is one of the best-established concepts in psychology (Baumeister et al., 2001). Evolutionarily, this makes sense: the cost of ignoring a threat is higher than ignoring something neutral.

Online, that bias means:

-

A headline designed to anger you feels more urgent.

-

A post that provokes moral disgust feels more important.

-

A comment that insults your group identity feels more personally meaningful.

Ragebait functions like an alarm bell. Even when the threat is artificial, our internal systems react as though it’s real.

2. Anger Spreads Faster Than Most Emotions

Emotion spreads socially—this is “emotional contagion.” But anger has special viral properties.

Studies of social networks show that anger is one of the most contagious emotions online because it is high-arousal, morally charged, and action-oriented (Brady et al., 2021). In a large analysis of Twitter posts, angry content spread faster and further than joyful or sad content (Schöne et al., 2021).

From a platform’s perspective, this is rocket fuel.

From a psychological perspective, it’s a recipe for escalation.

Ragebait doesn’t just make individuals angry; it makes communities angry together. And synchronized anger is extremely powerful.

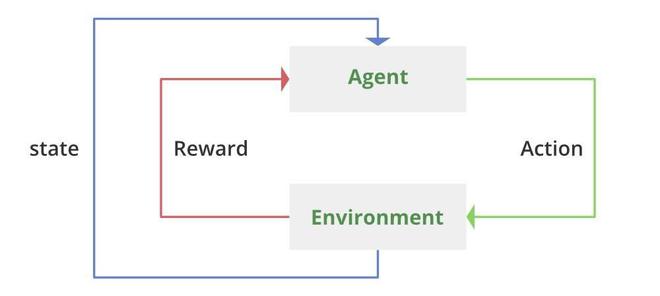

3. Reinforcement Learning

One cruelly simple fact explains the persistence of ragebait:

Anger generates engagement. Engagement generates rewards. Rewards generate more anger.

Every like, share, and indignation-filled comment signals to algorithms—and to content creators—that the post “worked.” This creates a reinforcement loop similar to operant conditioning (Skinner, 1953). Content designed to provoke outrage gets amplified; creators who learn this pattern repeat it.

The system doesn’t reward accuracy, empathy, or nuance.

It rewards reactivity.

4. Identity and Moral Signaling

Anger is not only an emotion; it is a form of communication. Expressing outrage serves as a public signal of moral identity—“I’m a good person because I’m furious about this.”

Research shows that moralized language increases engagement and that people often use outrage to signal loyalty to their group and disgust toward an out-group (Brady et al., 2017).

Ragebait exploits this impulse. It invites us to perform morality rather than practice it.

5. Misinformation Loves Outrage

A 2024 study in Science found that misinformation spreads most effectively when combined with moral outrage (McLoughlin et al., 2024). Ragebait makes false information:

-

easier to remember,

-

easier to believe, and

-

easier to share impulsively.

This is why ragebait is not just annoying—it is dangerous. It weaponizes our moral instincts against our ability to think critically.

The Social Amplifier Effect

Ragebait does not simply spark anger; it reshapes social dynamics.

Echo Chambers Become Combustion Chambers

Social identity theory predicts that groups will exaggerate differences with out-groups and minimize differences with in-groups (Tajfel, 1979). Ragebait accelerates this tendency. It encourages us to divide the world into:

- the people who “get it,”

- and the people we must fight.

The result?

Polarization increases, empathy decreases, and complex issues flatten into black-and-white narratives.

Communities Become More Hostile

When anger becomes the primary currency of a platform, hostility becomes the default tone. Sarcasm escalates into harassment. Criticism escalates into threats. Many users report emotional exhaustion and what some psychologists call “digital moral burnout.”

When the loudest voices are the angriest voices, quieter ones leave.

Who Creates Ragebait and Why?

Not all ragebait comes from the same place. It helps to distinguish between three types of creators:

1. The Money-Maximizers

Pages, influencers, or news outlets that use outrage as a business model. Their goal: clicks → ads → revenue. This is commercialized anger.

2. The Identity Entrepreneurs

These creators build personal brands around high-arousal outrage and polarizing hot-takes. Their goal: visibility, status, audience loyalty.

3. The Manipulators and Trolls

Political actors, coordinated networks, or provocateurs. Their goal: division, confusion, or ideological recruitment. Despite different motives, the strategy is identical: Provoke → outrage → engagement → spread.

The Psychological Cost to Individuals

- Emotional Exhaustion: Constant exposure to anger drains attentional and emotional resources, contributing to anxiety and irritability.

- Reduced Cognitive Complexity: Anger narrows attention. People think in more black-and-white terms and process information less deeply (Lerner & Keltner, 2001).

- Impulsive Behavior: Anger increases risk-taking and decreases impulse control, leading to reckless sharing or hostile interactions we later regret.

- Identity Rigidity: Frequent exposure to outrage can harden group identities, making compromise feel like betrayal.

So How Do We Resist?

- Slow Your Reaction by 10 Seconds: Even a brief pause reduces the likelihood of impulsive sharing. This uses the psychology of interruption to disrupt automatic emotional responses.

- Ask: “Who benefits if I share this?”: This simple question injects critical thinking into an emotional moment.

- Reframe Anger With Curiosity: Cognitive reappraisal—reinterpreting a situation more thoughtfully—reduces anger intensity (Gross, 1998).

- Curate Your Digital Environment: Algorithms reflect your engagement history. By refusing to feed ragebait, you alter the content you receive.

- Foster Group Norms That Reward Calm: Communities can counteract ragebait by encouraging thoughtful discourse, rewarding nuance, and discouraging dogpiling.

Policy and Platform Design

Psychology informs several potential reforms:

- Downranking High-Anger, Low-Information Content: Platforms can identify and reduce the spread of posts engineered for cheap outrage.

- Adding Friction to Sharing: Prompts such as “Would you like to read the article before sharing?” have been shown to reduce impulsive virality.

- Transparent Provenance: Labels showing the origin, funding, or network behavior of a post can reduce susceptibility to manipulative content.

- Designing for Slow Thinking: Features that highlight context, summarize claims, or flag emotionally manipulative language help users process content more reflectively.

None of these fixes eliminate outrage—nor should they. Anger is a vital emotional response to real injustice. But ragebait is not righteous anger; it is industrialized provocation designed for attention extraction.

Naming the Behavior Helps Us Fight It

What does it mean that Oxford chose ragebait?

It means society is collectively recognizing a psychological trap we’ve been falling into for years. Naming it reclaims some power.

Now we can point to harmful dynamics and say:

- This is not authentic conversation.

- This is an engagement tactic.

- This is ragebait.

Recognition is the first step toward resistance.

Conclusion

Ragebait won Word of the Year not because it’s clever, but because it’s revealing. It exposes a structural problem in the attention economy—one that feeds on predictable, universal features of human psychology.

Understanding why ragebait works doesn’t make us immune. But it gives us the tools to break the cycle: to pause, to reflect, and to choose when and how we engage.

If outrage is the fuel of the modern internet, then awareness is the firebreak.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Brady, W. J., Wills, J., Jost, J., Tucker, J., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(28), 7313–7318.

Brady, W. J., Crockett, M., & Van Bavel, J. (2021). The MAD model of moral contagion: The role of motivation, attention, and design in the spread of moralized content online. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1186–1203.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Lerner, J., & Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 146–159.

McLoughlin, K., Rathje, S., & Van Bavel, J. (2024). Misinformation exploits moral outrage to spread online. Science, 383(6672), 115–120.

Schöne, J. P., Parkinson, B., & Goldenberg, A. (2021). Negativity spreads more than positivity on Twitter after both. Scientific Reports, 11, 27374.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Tajfel, H. (1979). Individuals and groups in social psychology. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 183–190.

Oxford University Press. (2025). Oxford Word of the Year 2025 announcement. (No URL per instructions).

AP News. (2025). Ragebait named Oxford University Press word of the year.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 5). Ragebait and 5 Important Ways to Resist It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/ragebait/