When we think about breakups, we tend to imagine dramatic endings: shouting matches, tearful farewells, or the sudden sting of rejection. But many relationships end in silence — not with a bang, but with a fade. One or both partners slowly disengage, emotionally retreating long before anyone says the words “it’s over.”

This phenomenon, often called the quiet breakup, represents a subtle and psychologically complex process. Unlike explicit endings, quiet breakups unfold gradually, almost imperceptibly, as emotional bonds dissolve beneath the surface.

Read More: Psychology of Ghosting

What Is a Quiet Breakup?

A quiet breakup is not necessarily the end of a relationship on paper — it’s the emotional withdrawal that precedes it. It’s when one or both partners begin to detach internally, reducing intimacy, communication, and investment. The relationship technically continues, but the emotional core has already begun to collapse.

According to social psychologist Diane Vaughan (1986), many relationships end through a process she called the “uncoupling” phase, in which one partner mentally and emotionally exits the relationship long before a formal breakup. This pre-exit detachment is often invisible to outsiders — and even to the other partner.

During this phase, subtle behavioral changes appear: fewer affectionate gestures, diminished curiosity about each other’s inner lives, and an increasing emotional flatness. The silence grows louder than any argument.

Why Does Emotional Detachment Happen?

Quiet breakups don’t occur suddenly. They emerge through a series of small psychological shifts that, over time, create distance.

1. Emotional Exhaustion

One major cause of disengagement is emotional exhaustion — the burnout that results from prolonged dissatisfaction or unresolved conflict. When efforts to repair the relationship fail, partners may unconsciously withdraw to protect themselves.

Research on emotional labor (Hochschild, 1983) suggests that sustained efforts to manage feelings and maintain harmony can lead to depletion. In relationships, this exhaustion often manifests as indifference: it becomes easier to feel less than to feel frustrated again.

2. Avoidant Attachment

Attachment theory provides another lens for understanding quiet breakups. Individuals with avoidant attachment styles — shaped by early experiences of unreliable caregiving — often cope with relational stress by withdrawing (Bowlby, 1982).

When closeness feels threatening, the avoidant partner may create distance to maintain a sense of autonomy. This detachment is not necessarily intentional cruelty; it’s a learned defense mechanism. Studies have shown that avoidantly attached individuals deactivate emotional responses in intimate contexts, reducing both positive and negative affect to avoid vulnerability (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

3. The Illusion of Peace

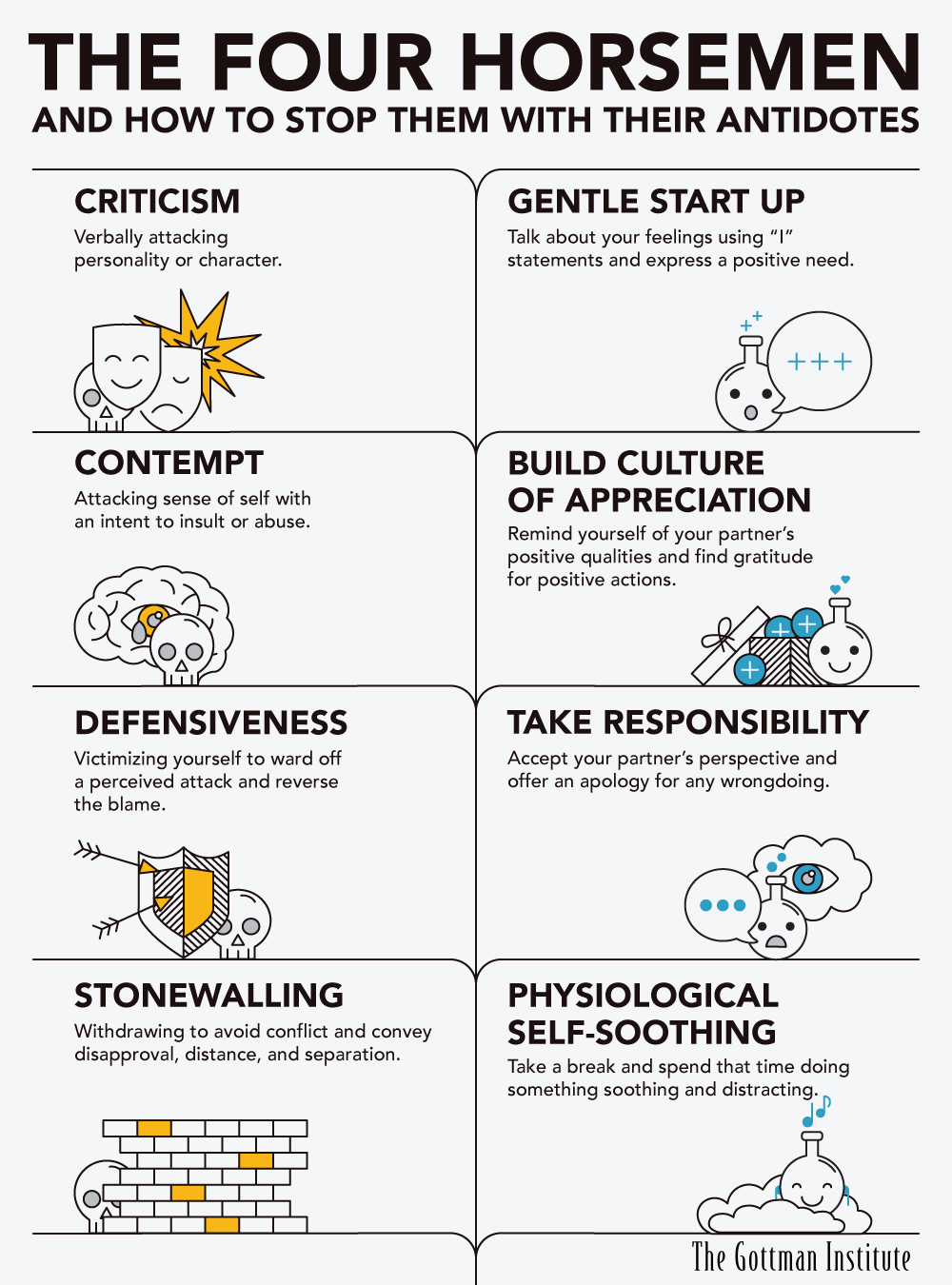

Paradoxically, silence can feel like safety. After repeated conflict, partners might equate the absence of fighting with improvement. But beneath that calm lies disconnection. Gottman and Levenson (1992) identified stonewalling — emotional withdrawal during conflict — as one of the strongest predictors of divorce.

Stonewalling often masquerades as maturity (“I’m not arguing anymore”) when in reality it signals emotional shutdown. Over time, emotional disengagement replaces active dialogue, eroding intimacy quietly.

4. Cognitive Dissonance and Emotional Numbing

When love fades but the relationship persists, cognitive dissonance emerges — the discomfort of holding two conflicting truths: “I care about this person, but I no longer feel connected.” To reduce that tension, people may numb themselves emotionally.

Research by Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, and Vohs (2001) on emotional intensity suggests that detachment is a common self-regulation strategy: by dulling feelings, individuals reduce psychological pain. The quiet breakup, therefore, becomes a coping mechanism — an anesthetic for impending loss.

5. Shifting Priorities and Identity Change

Relationships are dynamic, and so are people. As partners evolve, their goals, values, and sense of self may diverge. When this shift goes unspoken, emotional distance grows silently. According to Arriaga (2001), gradual declines in satisfaction often reflect mismatched growth rather than explicit conflict. The result is not anger, but quiet drifting — two parallel lives under one roof.

The Psychological Experience of the Quiet Breakup

The quiet breakup can be deeply painful precisely because it lacks clarity. Unlike a clean separation, where the rupture is visible and finite, emotional withdrawal creates ambiguous loss — a term coined by Pauline Boss (1999) to describe losses that are unclear and lack closure.

1. For the Partner Who Withdraws

The withdrawing partner often experiences ambivalence — a mix of guilt, confusion, and relief. They may feel trapped between wanting freedom and fearing the consequences of leaving. Emotional detachment becomes a way to “leave” without confronting guilt directly.

Some experience “emotional numbing”, where affection, empathy, and even irritation decline. This protective numbness minimizes distress but can also lead to moral discomfort: “I feel like I’m pretending.”

2. For the Partner Who’s Left Behind

The partner who remains emotionally invested often experiences confusion, anxiety, and self-doubt. They sense that something is “off” but can’t pinpoint what. Because the relationship hasn’t technically ended, they struggle to grieve properly.

Research shows that uncertainty in relationships can increase stress and preoccupation. Knobloch and Solomon (1999) found that relational uncertainty heightens cognitive rumination, leading to persistent worry and self-blame.

This ambiguity can be more distressing than an explicit breakup. It denies the closure necessary for emotional recovery.

Recognizing the Signs of Emotional Withdrawal

The quiet breakup is rarely announced, but it leaves detectable traces.

-

Reduced communication: Conversations become logistical (“Did you pay the bill?”) rather than emotional (“How are you really?”).

-

Loss of curiosity: Partners stop asking about each other’s experiences or inner thoughts.

-

Decreased physical affection: Touch becomes rare or perfunctory.

-

Avoidance of future talk: Plans, dreams, and “someday” conversations vanish.

-

Emotional neutrality: Instead of fighting, there’s apathy — the sense that nothing matters enough to argue about.

-

Social withdrawal: One partner spends increasing time outside the relationship — with friends, work, or hobbies.

These signs do not always mean a relationship is doomed, but they indicate a critical phase that requires awareness and communication.

The Role of Communication Avoidance

One of the key forces sustaining a quiet breakup is communication avoidance — the deliberate or unconscious evasion of difficult topics. Afifi and Guerrero (2000) found that partners avoid sensitive discussions for various reasons: to protect themselves from emotional pain, to avoid hurting the other, or to preserve fragile harmony.

Unfortunately, avoidance backfires. When issues remain unspoken, partners fill the silence with assumptions. Misinterpretations fester, and emotional distance deepens. Silence becomes both a symptom and a cause of detachment.

Emotional and Physiological Consequences

Emotional withdrawal is not merely relational; it affects mental and physical health.

1. Psychological Distress

Even if both partners “agree” to the quiet status quo, the emotional limbo can foster chronic stress. A study by Rhoades, Kamp Dush, Atkins, Stanley, and Markman (2011) found that individuals experiencing relationship dissolution reported significantly higher distress and lower life satisfaction compared to those in stable relationships.

2. Physiological Effects

Emotional isolation activates the body’s stress systems. Chronic detachment can elevate cortisol levels, impair sleep, and increase susceptibility to depression (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). The human brain interprets relational disconnection as a survival threat — echoing its evolutionary dependence on social bonds.

3. Identity Confusion

Relationships often shape self-concept. When emotional distance grows, individuals may feel disconnected from their own identity. Aron and Aron (1996) described how close relationships expand the self; losing that closeness, even gradually, can contract one’s sense of self and purpose.

How to Address a Quiet Breakup

While emotional detachment is painful, awareness offers an opportunity for growth. Not every quiet breakup must end in separation; sometimes, the silence signals a need for repair.

1. Acknowledge the Silence

Naming the disconnection is powerful. Saying “I feel we’re drifting apart” breaks the illusion of normalcy. Even if the conversation is uncomfortable, it transforms silent suffering into shared awareness — the first step toward clarity.

2. Rebuild Emotional Safety

Many quiet breakups stem from fear — fear of conflict, rejection, or vulnerability. Rebuilding requires re-establishing emotional safety, the sense that one can express truth without punishment. Gottman (1999) emphasized the importance of a “safe base” for intimacy, built through empathy, active listening, and nonjudgmental curiosity.

3. Decide: Repair or Release

Not all relationships can be saved, but all can be resolved with honesty. If both partners are willing, therapy or guided communication can help reignite emotional connection. However, if detachment is one-sided or irreversible, acknowledging the end allows both individuals to heal.

Vaughan (1986) observed that relationships often die long before they are buried. Bringing truth to light — even painful truth — allows for healthy mourning rather than lingering confusion.

4. Reconnect with Self

For both partners, recovery involves rediscovering selfhood outside the relationship. Practices like journaling, mindfulness, and social reconnection can rebuild identity and resilience. The goal is not to erase love’s memory but to integrate it as part of one’s growth narrative.

The Hidden Wisdom in the Quiet Breakup

Though painful, the quiet breakup offers profound lessons about emotional awareness. It reveals that relationships rarely end overnight — they fade in proportion to how communication, curiosity, and care fade.

Recognizing emotional withdrawal can also deepen empathy. Many people retreat not from malice but from fear: fear of confrontation, of hurting someone they still care for, or of facing their own unmet needs. Seeing the humanity beneath the silence transforms blame into understanding.

Finally, the quiet breakup underscores the need for emotional literacy — the ability to notice and articulate subtle shifts before they become chasms. Learning to name feelings early may not always save relationships, but it saves people from drifting unseen.

Conclusion

A quiet breakup is not simply a relationship ending — it’s a mirror reflecting how humans manage vulnerability, conflict, and love. It reminds us that absence of noise does not mean absence of pain.

Emotional withdrawal, though silent, leaves echoes. Yet within that silence lies choice: to remain numb or to face the truth with courage. Whether the outcome is repair or release, confronting the quiet breakup consciously turns an ending into a beginning — one that leads not just to loss, but to rediscovered wholeness.

References

Afifi, W. A., & Guerrero, L. K. (2000). Motivations underlying topic avoidance in close relationships. Communication Research, 27(2), 147–185.

Aron, A., & Aron, E. N. (1996). Self and self-expansion in relationships. In G. J. O. Fletcher & J. Fitness (Eds.), Knowledge structures in close relationships: A social psychological approach (pp. 325–344). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Arriaga, X. B. (2001). The ups and downs of dating: Fluctuations in satisfaction in newly formed romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(5), 754–765.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous loss: Learning to live with unresolved grief. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gottman, J. M. (1999). The seven principles for making marriage work. New York, NY: Crown.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 472–503.

Knobloch, L. K., & Solomon, D. H. (1999). A relational framing approach to uncertainty reduction in romantic relationships. Human Communication Research, 25(2), 243–274.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rhoades, G. K., Kamp Dush, C. M., Atkins, D. C., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: The impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(3), 366–374.

Vaughan, D. (1986). Uncoupling: Turning points in intimate relationships. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 9). The Quiet Breakup and 5 Important Reasons Why Emotional Detachment Happen. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/quiet-breakup/

Pingback: The Psychology of Online Dating and 7 Important Ways It Works - PsychUniverse