Introduction

In an increasingly fast-paced world, individuals often find themselves juggling numerous obligations, responsibilities, and unfinished tasks. This “mental clutter” can disrupt attention, impair productivity, and foster anxiety. Mental clutter refers to the accumulation of unresolved cognitive demands that continue to occupy attention even when one attempts to focus elsewhere (Masicampo & Baumeister, 2011). This phenomenon has roots in early 20th-century psychology, particularly in the work of Bluma Zeigarnik, who observed that people tend to remember unfinished tasks better than completed ones—a finding now known as the Zeigarnik Effect (Zeigarnik, 1927).

Read More- Decision Fatigue

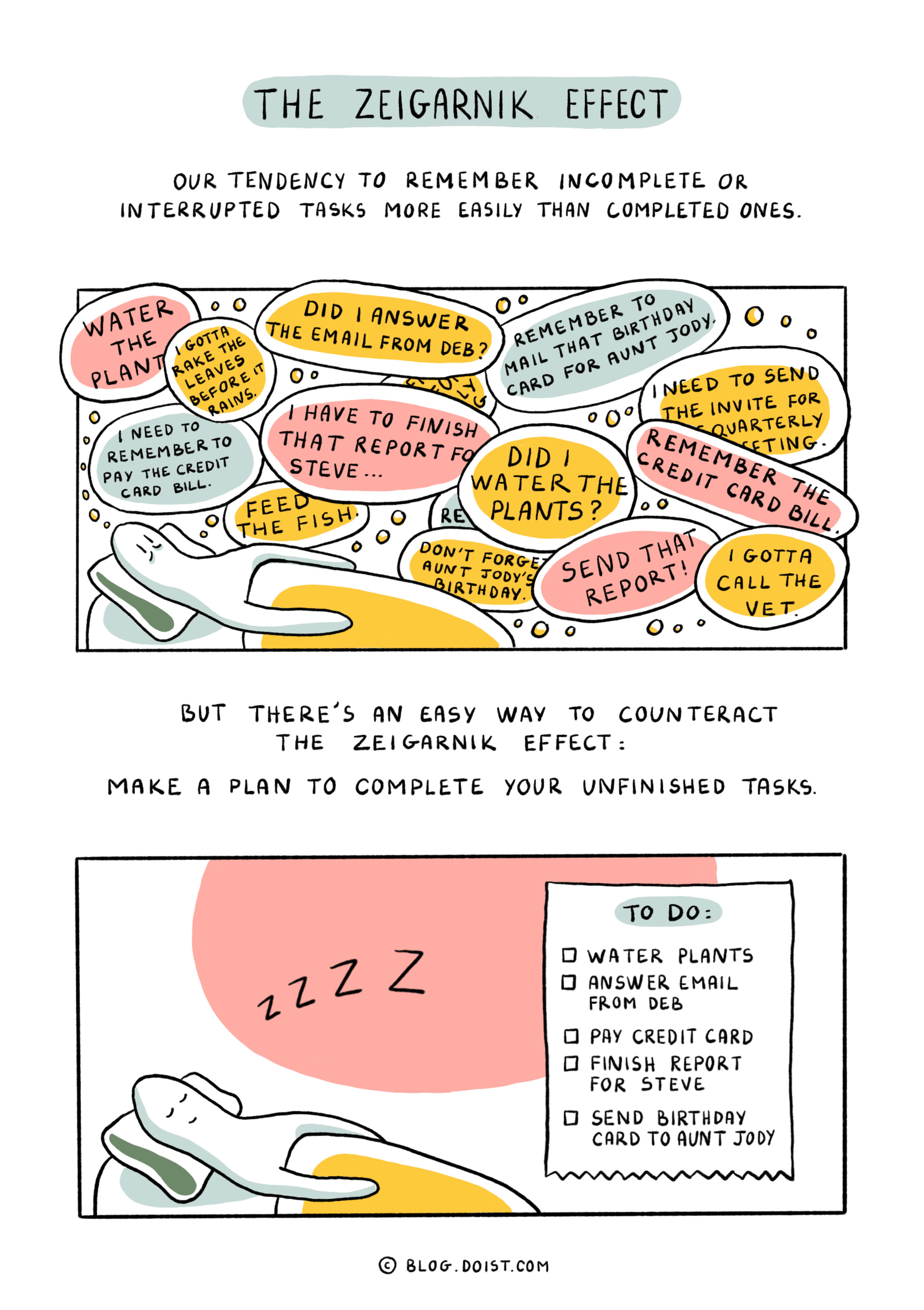

The Zeigarnik Effect

Bluma Zeigarnik (1927) first documented the effect that incomplete tasks have on memory and attention. While sitting in a café in Berlin, she observed that waiters had better recollections of orders that had not yet been paid. Once the bill was settled, memory of the order quickly faded. She later tested this empirically, finding that individuals recalled interrupted tasks about twice as often as completed ones.

The Zeigarnik Effect suggests that unfinished goals create a cognitive tension that persists until the task is completed or intentionally dismissed (Baumeister & Masicampo, 2010). This tension occupies space in working memory and competes for attentional resources (Kuhl & Goschke, 1994).

Cognitive Load and Executive Function

Mental clutter consumes working memory capacity, limiting one’s ability to process new information, reason, or make decisions (Baddeley, 2003). Working memory, a core component of executive function, has limited capacity, typically able to hold around 4–7 items at a time (Cowan, 2001). When this system is burdened by unresolved tasks, it can lead to diminished performance on tasks requiring focus and concentration.

Moreover, research by Altmann and Trafton (2002) on goal activation suggests that incomplete tasks remain active in long-term memory and can spontaneously re-enter consciousness, further disrupting attention and planning. This supports the idea that mental clutter not only occupies short-term cognitive resources but also disrupts long-term cognitive organization.

Emotional and Behavioral Consequences

Beyond cognitive interference, mental clutter has been associated with emotional distress. Unfinished tasks often cause anxiety, guilt, or frustration, particularly when they relate to personal or moral obligations (Sirois, 2007). These negative emotions can form a feedback loop, where avoidance leads to further procrastination and cognitive preoccupation, ultimately compounding the clutter.

Sirois and Pychyl (2013) found that procrastinators experienced higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, in part due to the persistent burden of tasks left incomplete. This shows the interplay between cognitive processes (incomplete task retention) and emotional regulation.

Mental Clutter in the Digital Age

In the modern digital landscape, mental clutter has taken on new dimensions. Notifications, emails, and multiple open tabs simulate the feeling of many “open loops,” even when no real action is needed. Marketers often exploit the Zeigarnik Effect using techniques like cliffhangers or incomplete prompts to hold audience attention (Li, 2015).

A 2017 study by Mark, Czerwinski, and Iqbal revealed that knowledge workers switch between digital tasks every 40 seconds on average, often without completing the previous task. This multitasking contributes to attentional residue and increases the cognitive cost of switching (Leroy, 2009).

Persistence of Incomplete Goals

Research supports the Zeigarnik Effect under certain conditions. Baumeister and Masicampo (2010) found that participants who were unable to complete assigned tasks performed worse on subsequent problem-solving tests compared to those allowed to finish. The unfinished task condition impaired cognitive performance due to lingering goal activation.

However, the effect can be context-dependent. Some studies suggest that the Zeigarnik Effect is more robust when the task is personally relevant or when individuals are intrinsically motivated to complete it (Koo & Fishbach, 2010).

Strategies to Manage Mental Clutter

Some strategies to manage it are:

1. Task Externalization

Writing down tasks is one of the most effective ways to offload them from working memory. Research by Masicampo and Baumeister (2011) showed that forming specific implementation intentions (e.g., “I will do X at Y time”) reduced the mental distraction caused by unfinished goals.

2. Batching and Micro-Completion

Breaking larger tasks into small, manageable sub-tasks (micro-completion) offers a psychological sense of progress. Amabile and Kramer (2011) termed this the “progress principle,” wherein small wins enhance motivation and reduce anxiety.

3. Time-Blocking and Closure Rituals

Scheduling specific time blocks for task completion can reduce the unpredictability of task intrusion. Moreover, closure rituals—such as reviewing the day’s tasks at night—can help the mind relax and reduce nocturnal rumination (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006).

4. Mindfulness and Meta-Cognition

Mindfulness practices improve cognitive flexibility and awareness of intrusive thoughts. A study by Zeidan et al. (2010) found that even brief mindfulness sessions significantly reduced mind-wandering and improved cognitive control.

Conclusion

Mental clutter—particularly in the form of unfinished tasks—places a measurable burden on cognitive and emotional resources. Rooted in the Zeigarnik Effect, this phenomenon underscores the importance of goal completion, attentional focus, and cognitive closure. By leveraging strategies such as task externalization, mindful planning, and micro-completions, individuals can regain cognitive bandwidth and enhance both performance and well-being. Future research should continue to refine our understanding of task-related cognitive interference in the context of the digital age.

References

Altmann, E. M., & Trafton, J. G. (2002). Memory for goals: An activation-based model. Cognitive Science, 26(1), 39–83. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2601_2

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. Harvard Business Press.

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829–839. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1201

Baumeister, R. F., & Masicampo, E. J. (2010). Consider it done! Plan making can eliminate the cognitive effects of unfulfilled goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 667–683. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020912

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X01003922

Furnham, A., & Marks, J. (2013). Tolerance of ambiguity: A review of the recent literature. Psychology, 4(09), 717. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.49102

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Koo, M., & Fishbach, A. (2010). Climbing the goal ladder: How the order of goal pursuit affects motivation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.003

Kuhl, J., & Goschke, T. (1994). A theory of action control: Mental subsystems, modes of control, and volitional conflict-resolution strategies. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Volition and personality: Action versus state orientation (pp. 93–124). Hogrefe.

Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residue when switching between work tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.04.002

Masicampo, E. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2011). Unfulfilled goals interfere with tasks that require executive functions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(2), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.10.011

Mark, G., Czerwinski, M., & Iqbal, S. T. (2017). Effects of individual differences in blocking workplace distractions. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(CSCW), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134702

Marsh, R. L., Hicks, J. L., & Bink, M. L. (2003). Activation of completed, uncompleted, and partially completed intentions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 29(3), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.29.3.395

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x

Salkovskis, P. M., Forrester, E., & Richards, C. (2000). Cognitive–behavioural approach to understanding obsessional thinking. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.3.217

Sirois, F. M. (2007). “I’ll look after my health, later”: A replication and extension of the procrastination–health model with community-dwelling adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.003

Sirois, F. M., & Pychyl, T. A. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12011

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9(1), 1–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02409755

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 5). The Psychology of Mental Clutter and 4 Important Strategies to Manage It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-mental-clutter/