Introduction

Most people experience an internal monologue—a steady stream of thoughts, evaluations, commentary, and self-directed language. This “inner narrator” acts as a psychological companion, guiding decisions, interpreting experiences, and shaping personal identity. Yet inner speech varies enormously from person to person. Some individuals have constant, vivid inner dialogues; others experience thoughts more as images, abstract concepts, or emotional sensations. Despite its central role in mental life, inner speech remains one of the least understood yet most influential aspects of human cognition.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

What Is the Inner Narrator?

The “inner narrator” is a form of inner speech, the silent use of language to reflect, plan, reason, or imagine. Inner speech has several components:

-

Verbal inner monologue – a running commentary using full sentences.

-

Dialogic inner speech – internal conversations between imagined voices or perspectives.

-

Condensed inner speech – brief verbal fragments representing larger concepts.

-

Evaluative inner speech – self-judgment, self-critique, or self-praise.

-

Motivational inner speech – self-encouragement, commands, and planning.

Vygotsky (1934/1987) argued that inner speech develops from early childhood external speech, gradually internalized as children learn to regulate behavior and emotion. This view remains foundational in modern psychology: the inner narrator is shaped by the language, tone, and dialog patterns a person grows up with.

Variations in Inner Speech

Many adults assume everyone thinks the way they do, yet research suggests incredible variation.

1. Differences in cognitive style

Some people are naturally verbal thinkers, while others rely more on imagery or sensory simulation (Paivio, 1971). Verbal thinkers tend to experience:

-

frequent internal sentences

-

detailed self-talk

-

strong inner commentary on experiences

Imagery-based thinkers often describe their thought world as:

-

visual scenes

-

emotional cues

-

physical sensations

2. Social and language environment

Children exposed to rich verbal interaction and explicit emotion labeling often develop more elaborate inner monologues. Conversely, children in environments with sparse dialogue or high emotional suppression may rely more on nonverbal cognitive strategies.

3. Personality

Traits like introspection, neuroticism, and openness are associated with more frequent inner dialogue, while extraversion and impulsivity correlate with less verbal internal processing.

4. Neurodiversity

Autistic individuals sometimes report less traditional inner speech and more pattern-based or sensory thinking. People with ADHD often have fragmented or rapid inner narrators. Those with anxiety disorders may experience an overly critical or hyperactive internal voice.

Thus, the inner narrator is neither universal nor fixed; it is shaped by biology, culture, and personal history.

The Function of Inner Speech

Psychologists have identified several key functions of internal monologue.

1. Self-Regulation

Inner speech helps people:

-

plan actions

-

inhibit impulses

-

evaluate behavior

-

solve problems step-by-step

Vygotsky proposed that inner speech evolved to regulate behavior the way caregivers originally guided children externally.

2. Memory and Encoding

Inner speech aids working memory through a system known as the phonological loop (Baddeley, 2012). Repeating items internally (“rehearsal”) helps with short-term retention and learning.

3. Emotional Processing

People use internal dialogue to:

-

comfort themselves

-

label emotions

-

reframe stressful events

-

express anger, fear, or frustration

Healthy inner narrators help regulate emotions; unhealthy ones can intensify distress.

4. Identity Construction

Internal narratives form the backbone of personal identity. According to narrative psychology, individuals build a sense of self by converting life events into a coherent story (McAdams, 2001). Inner speech acts as the storyteller.

5. Simulation of Social Interactions

Dialogic inner speech allows people to rehearse conversations, anticipate reactions, and reflect on relationships. This mental simulation can improve social skills—but can also fuel rumination or anxiety when overused.

When the Inner Narrator Turns Against Us

Although inner speech is vital for mental functioning, it can become problematic.

1. Overactive Inner Critic

Many individuals struggle with self-critical inner monologues developed from parental criticism, trauma, or perfectionism. This voice may:

-

magnify failures

-

predict negative outcomes

-

shame the self for mistakes

-

undermine motivation

Research links harsh internal dialogues with depression and anxiety (Beck, 1976).

2. Rumination

Rumination occurs when the inner narrator loops negative thoughts repeatedly. Excessive rumination is associated with:

-

major depressive disorder

-

social anxiety

-

generalized anxiety

-

PTSD

It often masquerades as “problem solving,” but actually traps individuals in repetitive evaluation without resolution.

3. Catastrophizing and Imagined Dialogue

Some people experience a narrator that exaggerates threats or imagines worst-case scenarios. Others replay or rehearse conversations excessively, a phenomenon called “intrusive social simulation.”

4. Dissociated or Fragmented Inner Speech

Trauma survivors may experience fragmented or disconnected internal voices, reflecting disruptions in memory and self-coherence.

The Neuroscience of the Inner Narrator

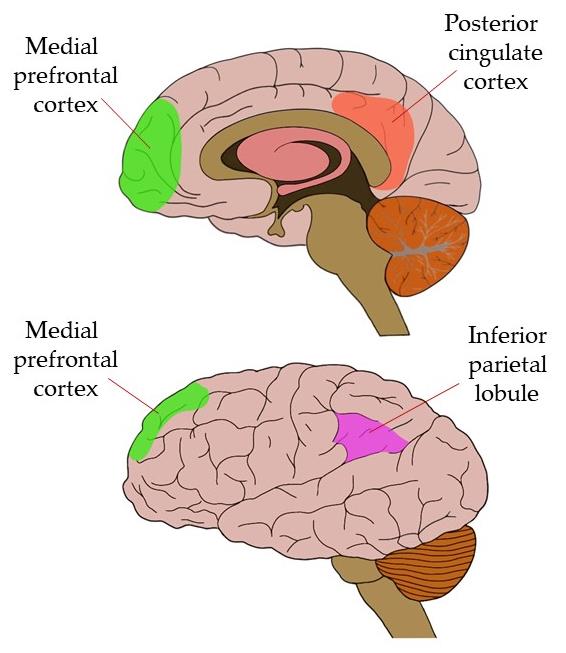

Functional neuroimaging studies show that inner speech activates brain regions involved in speech production, social cognition, and autobiographical memory.

Key regions include:

-

Broca’s area – involved in speech generation

-

Superior temporal gyrus – linked to speech perception

-

Default mode network (DMN) – active during self-referential thought

-

Prefrontal cortex – planning and regulation

Interestingly, dialogic inner speech—internal conversations between different “voices”—engages brain regions associated with theory of mind, suggesting the brain treats these internal voices like separate agents.

Some researchers propose that when the system that monitors internal speech breaks down, inner dialogue may be misattributed as external—potentially contributing to auditory hallucinations in psychotic disorders (Jones & Fernyhough, 2007).

Cultural Differences in Inner Narrators

Inner speech is shaped by culture in surprising ways:

Individualistic cultures

Often emphasize introspection, internal autonomy, and personal identity, leading to more elaborate self-focused internal monologues.

Collectivistic cultures

May promote internal dialogues oriented toward family expectations, social harmony, and moral duty.

Cultures with rich oral traditions

Often report vivid narrative inner speech reflecting storytelling patterns.

Cross-cultural studies show that inner narrators reflect cultural norms as much as personal experiences.

Silence Within

Some individuals report having little to no internal monologue. Instead, they think through:

-

visual images

-

abstract conceptual structures

-

emotional impressions

This phenomenon is normal and not reflective of any deficit. It challenges assumptions about cognition and highlights human diversity in thought processes.

People without strong inner narrators often excel in visual-spatial tasks or intuitive problem solving.

Cultivating a Healthy Inner Narrator

Psychological interventions often focus on transforming dysfunctional inner speech.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Teaches individuals to identify and challenge maladaptive internal dialogue (Beck, 1976).

- Self-Compassion Training: Encourages replacing harsh self-talk with kinder, supportive internal language (Neff, 2011).

- Mindfulness Practices: Reduce the intensity and stickiness of inner monologues by shifting attention from verbal thought to present-moment awareness.

- Narrative Therapy: Helps individuals rewrite personal stories to foster empowerment and coherence (White & Epston, 1990).

- Expressive Writing: Externalizes inner dialogue, helping disorganize thoughts become structured and processed (Pennebaker, 1997).

A goal is not to silence the narrator but to make it a constructive guide rather than an inner adversary.

The Future

AI tools increasingly allow people to externalize, observe, and interact with their inner thoughts. Future technologies may visualize or reconstruct inner speech, potentially helping with psychotherapy, self-regulation, or creativity. However, concerns about privacy, authenticity, and emotional dependence remain.

As technology evolves, our relationship to internal language may shift dramatically—possibly blurring the boundary between inner and outer thought.

Conclusion

The inner narrator is a core component of human psychology. It guides decisions, shapes identity, influences emotion, and constructs meaning. Yet it varies widely among individuals and cultures. Understanding the nature of inner speech reveals how people perceive themselves and the world.

A healthy inner narrator can be a source of strength, clarity, and resilience. An unhealthy one can distort reality and erode well-being. By studying and cultivating inner speech, psychology continues to uncover one of the most intimate aspects of the human mind.

References

Baddeley, A. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1–29.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press.

Fernyhough, C. (2016). The Voices Within: The History and Science of How We Talk to Ourselves. Profile Books.

Jones, S. R., & Fernyhough, C. (2007). Inner speech and auditory verbal hallucinations: A review and clinical implications. Psychological Medicine, 37(12), 1635–1643.

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and Verbal Processes. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166.

Vygotsky, L. (1987). Thinking and Speech. In R. Rieber & A. Carton (Eds.), The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 1). Plenum. (Original work published 1934)

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. Norton.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 23). The Psychology of Inner Narrator Voices and 4 Important Variations in It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-inner-narrator-voices/