Introduction

We often think of creativity as lightning—sudden, unpredictable, and uncontrollable. The myth of the “creative genius” suggests that only a few gifted minds are capable of producing great ideas, while the rest of us merely admire them. Yet modern psychology paints a different picture. Creativity isn’t a mysterious gift—it’s a process rooted in the brain’s natural capacity to connect, combine, and reimagine information in novel ways.

From artists and inventors to entrepreneurs and scientists, creativity drives human progress. But what exactly happens in the mind when we’re being creative? And why do moments of brilliance often arise out of boredom, chaos, or even failure?

Read More: Grandma Core

Defining Creativity

Psychologists typically define creativity as the ability to produce ideas or outcomes that are both novel and useful (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). This dual requirement—originality and practicality—distinguishes creativity from mere imagination.

Creativity also isn’t limited to artistic expression. It manifests in scientific breakthroughs, problem-solving, entrepreneurship, and even daily improvisations like cooking with limited ingredients or finding a faster route to work.

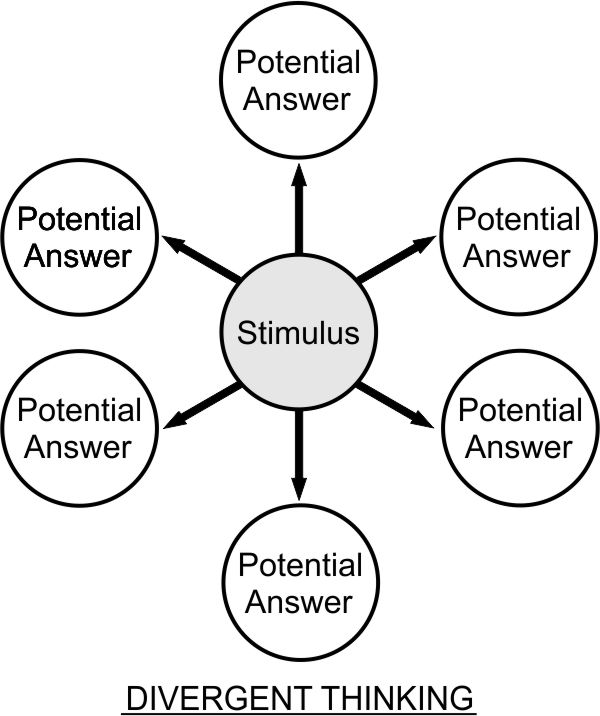

According to Guilford (1950), one of the pioneers of creativity research, creative thinking involves divergent thinking—the ability to generate multiple, varied solutions to a problem—rather than just converging on a single “right” answer. This flexible, open-ended thinking style allows people to make unexpected associations between concepts.

The Creative Brain

Neuroscience has revealed that creativity doesn’t belong to one “creative” region of the brain. Instead, it arises from the dynamic interaction of several neural networks:

-

The Default Mode Network (DMN) – active during daydreaming, imagination, and spontaneous thought; generates ideas.

-

The Executive Control Network (ECN) – evaluates and refines ideas; responsible for focus and decision-making.

-

The Salience Network – toggles between the DMN and ECN, deciding when to let the mind wander and when to apply control (Beaty et al., 2016).

When these systems communicate fluidly, the brain moves between idea generation and idea evaluation, the two essential stages of creativity. This neural “dance” is why some of our best ideas emerge when we’re relaxed or distracted—the DMN is most active when the mind isn’t deliberately focusing on a task.

Chaos as the Birthplace of Creativity

Contrary to the idea that creativity requires perfect conditions, many creative breakthroughs come from chaos, disorder, or constraint. When routines are disrupted, the brain is forced to reorganize patterns and make new connections.

Research shows that a moderate level of distraction can actually enhance creative performance (Mehta et al., 2012). Similarly, ambiguous environments—like messy desks or unpredictable challenges—encourage exploration and flexible thinking (Vohs et al., 2013).

Why? Because creativity thrives on cognitive flexibility—the ability to shift perspective, reinterpret information, and adapt to change. Environments or experiences that challenge comfort zones stimulate this flexibility, prompting the mind to “recombine” ideas in unexpected ways.

Chaos, then, isn’t the enemy of creativity—it’s often its catalyst.

The Paradox of Constraints

While chaos fosters novelty, too much freedom can be paralyzing. The paradox of creativity is that constraints can enhance innovation.

When faced with limits—time pressure, scarce resources, or specific rules—people are forced to think resourcefully. A study by Stokes (2006) found that boundaries push individuals to explore unconventional strategies, leading to more original outcomes.

Think of poets writing haikus, filmmakers working on a budget, or startups innovating with minimal resources. Constraints provide structure, narrowing infinite possibilities into a manageable framework where imagination can flourish.

Psychologist Patricia Stokes (2006) called this “constraint-based creativity”—a process where limits become creative triggers. Boundaries act like the edges of a canvas: without them, there’s nothing to paint on.

Personality and Creativity

Not everyone approaches chaos and constraint the same way. Personality traits play a major role in creative potential.

The Big Five personality model identifies openness to experience—curiosity, imagination, and preference for novelty—as the trait most strongly correlated with creativity (Feist, 1998). Creative individuals tend to embrace complexity and ambiguity rather than seek simple answers.

They’re also more comfortable with uncertainty—a psychological trait known as tolerance for ambiguity (Budner, 1962). This ability to stay calm amid confusion allows creative thinkers to explore ideas without prematurely rejecting them.

Interestingly, creative people often show traits of nonconformity and intrinsic motivation. They’re driven by curiosity and meaning rather than external rewards (Amabile, 1996). This internal drive sustains the long, often frustrating process of experimentation and failure that creativity requires.

The Flow State

If chaos and constraint describe the conditions for creativity, flow describes its experience. Coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990), flow is a mental state of complete absorption in an activity where time disappears, self-consciousness fades, and performance reaches its peak.

Flow occurs when challenge and skill are perfectly balanced—when a task is demanding enough to stretch abilities but not so difficult that it causes anxiety. Musicians often call it being “in the groove,” athletes call it “the zone,” and writers call it “losing themselves in the work.”

During flow, dopamine and norepinephrine surge, enhancing focus and pleasure (Dietrich, 2004). Brain scans show decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex—a temporary relaxation of the brain’s inner critic—allowing freer expression and risk-taking.

In other words, flow is the neurological opposite of overthinking. It’s the mind’s most effortless form of focus, where creativity feels natural rather than forced.

The Role of the Subconscious

Ever noticed that your best ideas arrive in the shower or on a walk, not at your desk? That’s the incubation effect—the creative process continuing subconsciously after a period of rest or distraction (Sio & Ormerod, 2009).

When we step away from a problem, the brain continues processing it in the background, forming new associations beyond conscious awareness. This explains the sudden “Aha!” moments described by Archimedes, Einstein, and countless others.

Psychologists call this the insight problem-solving process, where the mind restructures information suddenly rather than through step-by-step reasoning (Kounios & Beeman, 2009). The insight often feels spontaneous, but it’s really the result of deep, unseen processing.

The Dark Side of Creativity

While creativity is celebrated as a virtue, it can have darker edges. High levels of creative potential are sometimes linked with emotional instability, mood disorders, and even risk-taking behavior (Carson, 2011).

The same openness and sensitivity that fuel creativity can make individuals more vulnerable to stress or self-doubt. Studies have shown correlations between creative professions and elevated rates of bipolar disorder and depression (Jamison, 1993).

However, creativity can also serve as a protective outlet—a way to process and transform difficult emotions into meaning. Artistic expression and problem-solving often provide psychological relief and resilience.

Cultivating Creativity

The good news is that creativity isn’t fixed—it can be nurtured through habits and mindset. Research offers several strategies to enhance creative thinking:

1. Embrace Boredom

When the mind isn’t overstimulated, it defaults to the DMN, which generates spontaneous ideas. Studies show that periods of boredom can actually increase creativity (Mann & Cadman, 2014).

2. Switch Contexts

Engaging in unrelated activities, traveling, or learning new skills introduces fresh stimuli, promoting cognitive flexibility.

3. Use Constraints Wisely

Set challenges—like time limits or specific formats—to focus imagination within boundaries. Too many choices can overwhelm; just enough can ignite originality.

4. Practice Mindfulness

Mindfulness reduces cognitive clutter and enhances the ability to notice subtle associations, fostering insight (Colzato et al., 2012).

5. Collaborate

Creativity flourishes in social environments where diverse perspectives collide. Group brainstorming, if structured well, can amplify collective intelligence.

6. Detach from Perfection

Fear of failure suppresses experimentation. Creative work improves through iteration, not idealization.

Creativity in the Modern World

In an era of automation and artificial intelligence, creativity is increasingly viewed as the most valuable human skill. Machines can analyze data and replicate patterns, but true creativity—the capacity to generate original meaning—remains uniquely human.

Yet, our attention economy often undermines creative potential. Constant digital stimulation leaves little room for reflection or boredom, both of which are crucial for idea incubation. Reclaiming solitude and slowing down may be the most revolutionary acts of creativity today.

Conclusion

Creativity is not magic—it’s a dance between chaos and control, freedom and constraint, effort and surrender. It’s a universal human capacity that thrives when we balance structure with spontaneity, discipline with play, and curiosity with courage.

When we stop waiting for inspiration and start engaging with life’s messiness, creativity naturally emerges. It’s not something we find—it’s something we cultivate.

As Csikszentmihalyi (1990) wrote, “The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times… but the ones in which we are fully engaged.”

In other words, creativity is not just about making things—it’s about being alive in the fullest sense.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. Westview Press.

Beaty, R. E., Benedek, M., Silvia, P. J., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Creative cognition and brain network dynamics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(2), 87–95.

Budner, S. (1962). Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. Journal of Personality, 30(1), 29–50.

Carson, S. (2011). Creativity and psychopathology: A shared vulnerability model. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(3), 144–153.

Colzato, L. S., Ozturk, A., & Hommel, B. (2012). Meditate to create: The impact of focused-attention and open-monitoring training on convergent and divergent thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 116.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Dietrich, A. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11(6), 1011–1026.

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 290–309.

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454.

Jamison, K. R. (1993). Touched with fire: Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. Free Press.

Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2009). The Aha! moment: The cognitive neuroscience of insight. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 210–216.

Mann, S., & Cadman, R. (2014). Does being bored make us more creative? Creativity Research Journal, 26(2), 165–173.

Mehta, R., Zhu, R. J., & Cheema, A. (2012). Is noise always bad? Exploring the effects of ambient noise on creative cognition. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 784–799.

Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96.

Sio, U. N., & Ormerod, T. C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 94–120.

Stokes, P. D. (2006). Creativity from constraints: The psychology of breakthrough. Springer.

Vohs, K. D., Redden, J. P., & Rahinel, R. (2013). Physical order produces healthy choices, generosity, and conventionality, whereas disorder produces creativity. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1860–1867.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 11). The Psychology of Creativity and 3 Important Networks of Creativity. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-creativity/