Addiction is one of the most misunderstood psychological phenomena. To many, addiction looks like a failure of willpower—an inability to control oneself or make rational decisions. But decades of neuroscience and psychology research paint a very different picture. Addiction is not a matter of choice; it is a disorder rooted in how the brain processes reward, stress, and motivation.

At its core, addiction hijacks the brain’s most fundamental learning systems. It rewires how we seek pleasure, how we cope with distress, and how we form memories of what we believe we “need” to survive. Understanding this process is essential for supporting individuals struggling with addictive behaviors, whether related to substances, gambling, gaming, or digital dependence.

Read More: Hope Theory

The Brain’s Reward System

The brain has an elegant system designed to reinforce behaviors that promote survival: eating, bonding, exploration, achievement. Dopamine, one of the key neurotransmitters involved, sends signals that tell us:

- “This feels good.”

- “Remember this experience.”

- “Seek it again.”

The mesolimbic dopamine pathway—particularly the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens—is central to this reinforcement system (Volkow & Morales, 2015). When something is pleasurable, this circuit helps us learn and repeat the behavior.

Addictive substances and behaviors exploit this very mechanism.

Addictive Behaviors Cause Abnormally High Dopamine Surges

Natural rewards (like food or socializing) increase dopamine by about 50–100%. Addictive substances can raise dopamine levels by:

- nicotine: 200%

- alcohol: 100–200%

- opioids: 300–500%

- cocaine and methamphetamine: up to 1,000%

These massive surges overwhelm the brain. The nervous system interprets the experience as incredibly important—more important than natural survival behaviors.

In psychological terms, this creates powerful reinforcement learning. The brain stores detailed memories of:

- where the substance was used

- who was present

- emotional context

- environmental cues

This is why seemingly small details can trigger intense cravings even after long periods of abstinence.

Addiction Is Not About Pleasure, It’s About Compulsion

Many people assume individuals return to addictive behaviors because they feel good. But research shows that as addiction develops:

- pleasure decreases

- craving increases

- compulsion becomes dominant

Koob & Le Moal (2006) describe this as a shift from positive reinforcement (seeking pleasure) to negative reinforcement (avoiding discomfort and withdrawal).

Eventually, people use substances not to feel high—but to feel normal.

Tolerance

When dopamine levels remain artificially high, the brain adapts by reducing receptor sensitivity. This leads to tolerance:

- more substance is needed to achieve the same effect

- normal pleasures feel dull or meaningless

- everyday life becomes exhausting or flat

This neurological adaptation is not psychological weakness—it is the brain’s attempt to restore equilibrium.

Sadly, tolerance often drives further consumption, creating a destructive cycle.

Withdrawal

Once the brain is accustomed to elevated dopamine levels, the sudden absence of the substance creates a crash:

- irritability

- anxiety

- insomnia

- physical pain

- mood swings

- intense cravings

This withdrawal response is one of the strongest forces driving compulsive use.

Stress, Trauma, and Emotional Regulation

Addiction is not solely about reward—it’s also about relief.

The brain’s stress system (involving the amygdala, hypothalamus, and cortisol pathways) interacts closely with reward circuits. Individuals with a history of:

- trauma

- chronic stress

- emotional neglect

- anxiety

- depression

are significantly more vulnerable to addiction. Substances temporarily reduce negative emotions, which reinforces use.

In this sense, addiction often becomes a strategy for emotional survival.

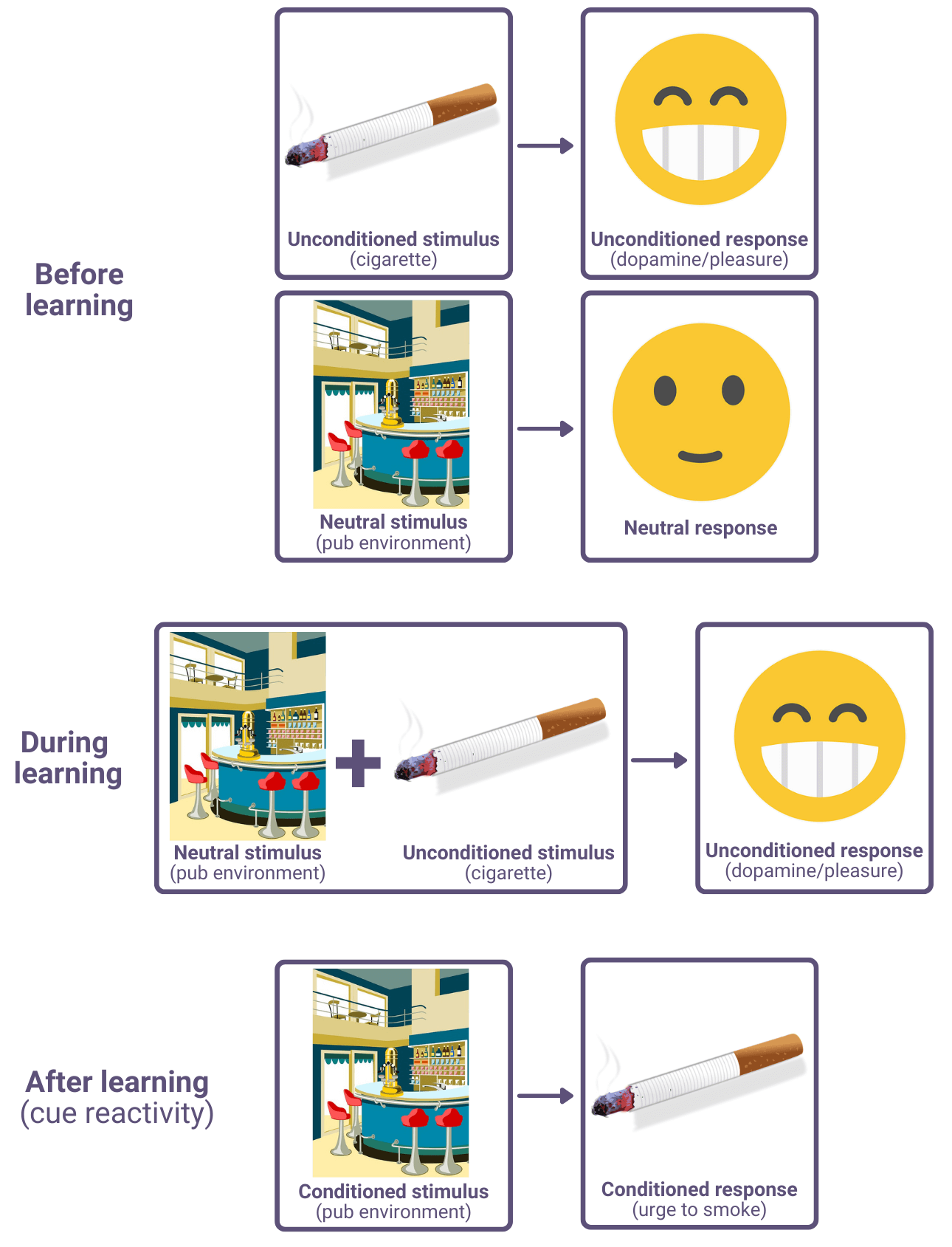

The Role of Memory and Learning in Cravings

Addiction deeply engrains memories associated with the substance. These memories—called conditioned cues—can trigger cravings automatically.

A person might crave alcohol simply by:

- passing their favorite bar

- hearing a bottle cap

- smelling cigarette smoke

- seeing certain people

- feeling a certain emotion

These reactions are not conscious decisions—they are automatic neural responses encoded in memory.

Social and Environmental Influences

Addiction is not purely biological. Social psychology provides important insight into environmental contributors:

- peer influence

- availability of substances

- cultural norms

- family modeling

- socioeconomic stress

- loneliness and isolation

Environments that provide fewer healthy coping mechanisms and more stressors increase vulnerability.

Why Some People Become Addicted and Others Don’t

Addiction vulnerability is shaped by:

- Genetics: Up to 50% of addiction risk is hereditary.

- Temperament: Impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and emotional reactivity increase risk.

- Trauma History: Strong predictor of compulsive behaviors.

- Mental Health: Depression, ADHD, PTSD, and anxiety often precede addiction.

- Environment: Stress, instability, and access to substances play major roles.

Addiction arises from a complex interaction of these factors—not simply “poor choices.”

The Prefrontal Cortex

Addiction weakens the brain’s executive-control center: the prefrontal cortex. This area governs:

- decision-making

- impulse control

- planning

- self-regulation

As addiction progresses, this system becomes compromised. The result is:

- difficulty resisting urges

- poor long-term decision-making

- compulsive behavior

- reduced ability to pause and reflect

This neurological impairment explains why people with addiction continue harmful behavior despite knowing the consequences.

The Myth of “Willpower”

Addiction changes brain function at structural and chemical levels. Expecting someone to quit through willpower alone is unrealistic and often harmful.

Recovery requires:

- medical support

- psychological treatment

- social connection

- environmental change

- coping skills

- time

Willpower is a tool—not a solution.

Behavioral Addictions Mirror Substance Addictions

Gambling, gaming, pornography, shopping, and even social media activate the same reward circuits as substances.

Dopamine spikes from:

- unpredictable rewards

- likes and notifications

- wins and losses

- novelty

Because the brain learns patterns predictively, variable reward schedules (like gambling) are especially addictive.

Recovery

The good news: the brain is remarkably plastic.

Over time, reduced exposure to addictive stimuli allows:

- dopamine levels to stabilize

- receptor sensitivity to recover

- prefrontal cortex functioning to improve

Therapeutic strategies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, medication-assisted treatment, mindfulness, and peer support have strong evidence bases.

Recovery is not linear—but it is possible.

Conclusion

Addiction is not a character flaw. It is a complex psychological and neurological condition that rewires the brain’s fundamental reward systems. Understanding addiction as a learning process gone awry—rather than a moral failing—allows for more effective treatment, greater compassion, and reduced stigma.

People with addiction are not weak or broken. They are individuals whose brains have adapted to survive overwhelming emotions, trauma, or stress. With proper support, their brains can adapt again—toward healing, balance, and resilience.

References

Koob, G. F., & Le Moal, M. (2006). Neurobiology of Addiction.

Volkow, N. D., & Morales, M. (2015). The brain on drugs: From reward to addiction. Cell.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.).

Hyman, S. E. (2005). Addiction: A disease of learning and memory. American Journal of Psychiatry.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2008). The incentive sensitization theory of addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 14). The Psychology of Addiction and 5 Powerful Etiology Behind It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-addiction/