Psyched for Books

Welcome to the first entry of “Psyched for Books” — a monthly series where we crack open a psychology book (or a book steeped in psychology) and explore its ideas, insights, and quirks. Think of it as our collective ritual: each month begins with a new lens into the human mind. Some books will be practical, some philosophical, and some deeply personal. All will leave us with food for thought (and maybe some fun “aha!” moments).

Since last month was September and it is recognized worldwide as Suicide Awareness & Prevention Month, it feels not only timely but urgent to begin with one of the most influential books on this subject: Why People Die by Suicide (2005) by clinical psychologist Thomas Joiner. This book is part science, part personal reckoning, and part call to action. It confronts one of the most stigmatized questions in psychology with clarity, compassion, and (believe it or not) moments of unexpected humanity.

And hey — if you’ve ever thought, “Wow, I’d totally join a PsychUniverse book club,” we might just make it happen! Imagine a cozy corner of the internet where we geek out over psychology reads together. If that sounds like your vibe, drop a comment below or shoot us an email at psychuniverseofficial@gmail.com, your vote could turn Psyched for Books into a full-blown book club adventure!

Read More: Suicide Prevention and Awareness Month

Why this book, and why now?

Suicide is one of the most pressing global health issues, claiming close to 700,000 lives annually (World Health Organization, 2021). Talking about it directly, with care and knowledge, is part of prevention. Joiner’s work gives us a framework that is both accessible and powerful.

What makes Joiner’s perspective especially compelling is that he approaches suicide as both a scientist and a grieving son. His father died by suicide when Joiner was in graduate school, and that lived experience gives his writing a rare blend of empathy and urgency (Joiner, 2005).

Last month was the suicide awareness and prevention month. At the end of the month, we reflect and align with the month’s central message: awareness is prevention. We’re not just looking at grim statistics — we’re gaining a vocabulary, a theory, and a direction for hope.

A Quick Overview of the Book

Why People Die by Suicide seeks to answer the haunting question: why do some people end their lives, despite our natural instinct to survive? Joiner acknowledges that no single explanation can account for all cases. But he argues that the countless risk factors we know of — psychiatric illness, trauma, genetics, substance abuse — funnel through a narrower set of psychological processes.

The book unfolds in three broad parts:

- Surveying what we know (and don’t know) — prevalence, myths, and cross-cultural insights.

- The interpersonal theory of suicide — Joiner’s central model, which we’ll unpack below.

- Implications for prevention and treatment — how understanding the model can guide action.

Joiner weaves together clinical research, personal anecdotes, and even literary references to create a theory that is both rigorous and relatable (Joiner, 2005).

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

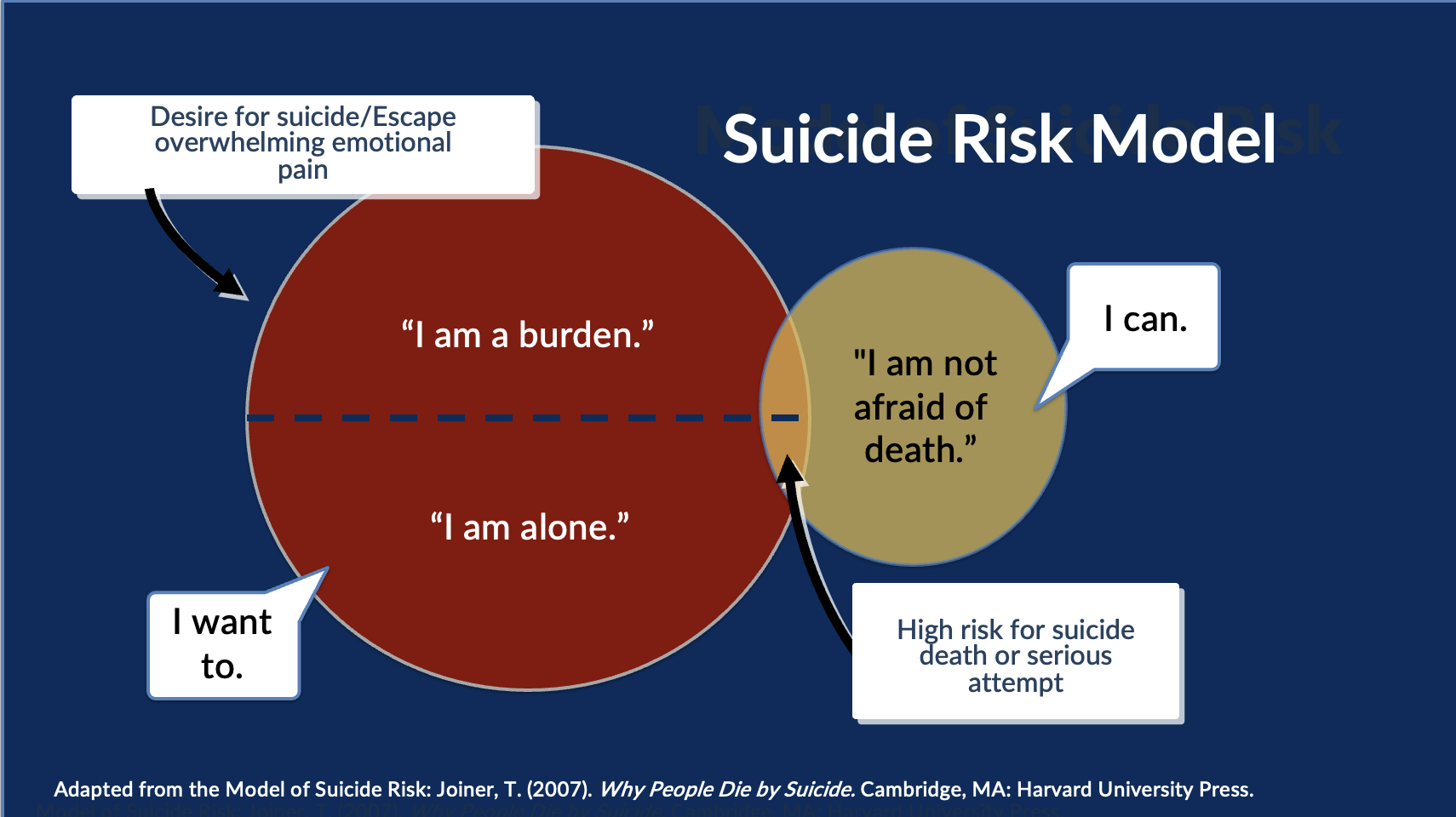

The book’s centerpiece is the interpersonal theory of suicide, a model that has since become widely cited in suicide research. In simple terms, Joiner argues that suicidal behavior requires both the desire to die and the capability to act on that desire.

1. Desire for suicide

- Thwarted belongingness is the painful feeling of not being connected, of being isolated or alienated from others. Loneliness and social rejection fuel this perception.

- Perceived burdensomeness is the belief that one’s existence harms others — that “my death would be worth more than my life to the people I love.” This is often a distorted perception, but it can feel unbearably real (Joiner, 2005).

When these two forces co-occur and feel hopelessly permanent, the desire for death intensifies (Van Orden et al., 2010).

2. Capability for suicide

But desire alone doesn’t translate into action. According to Joiner, people also need the capability to enact lethal self-harm — which means overcoming the natural fear of death and the instinct to avoid pain.

This capability is not innate; it is acquired through repeated exposure to painful or provocative experiences. Combat veterans, physicians, or people who have engaged in self-harm, for example, may gradually become more fearless in the face of pain and death (Joiner, 2005). This explains why prior suicide attempts are among the strongest predictors of future attempts (Klonsky & May, 2015).

Thus, serious risk arises when the desire (belongingness + burdensomeness) intersects with capability.

“Suicide is a tragic outcome of two psychological states coming together: a sense of thwarted belongingness and the perception of being a burden to others, combined with the acquired capability to inflict lethal self-harm. These states interact in ways that can make life feel unbearably painful, and yet, paradoxically, the very factors that lead someone toward suicide can often be alleviated through connection, understanding, and human empathy.” (Joiner, 2005, p. 126)

Strengths of Joiner’s Model

- Clarity and simplicity: Instead of sprawling lists of risk factors, the theory distills suicide into three interacting dimensions — belongingness, burdensomeness, and capability.

- Clinical usefulness: The framework suggests actionable strategies: build belonging, challenge burdensomeness beliefs, and reduce exposure to habituating pain (Van Orden et al., 2010).

- Integration of why and how: Many models explain why people want to die, but not how they overcome fear. Joiner covers both.

- Empathetic grounding: His personal connection to the topic keeps the book from feeling like a detached academic exercise.

Limitations

No theory is flawless. Some critiques include:

- Overreach: Joiner occasionally stretches the theory to fit diverse data, which can feel forced (Hjelmeland & Knizek, 2010).

- Testing challenges: While components of the theory (e.g., burdensomeness) have strong empirical support, the full three-part model is harder to validate consistently (Ma, Batterham, Calear, & Han, 2016).

- Exclusions: Factors like impulsivity, substance use, or cultural differences don’t always map neatly onto the theory (Chu, Goldblum, Floyd, & Bongar, 2010).

- Style: Some readers find the writing repetitive or heavy with jargon.

Still, the interpersonal theory remains a touchstone in suicidology — widely cited, debated, and refined.

Memorable Insights

Several parts of the book leave a lasting impression:

- The bridge anecdote: Joiner references a suicide note that read: “I’m going to walk to the bridge. If one person smiles at me on the way, I will not jump.” This illustrates the fragility of suicidal desire and the power of tiny gestures of human connection.

- Fearlessness as learned: The chilling idea that people can “train” themselves into fearlessness reframes suicide as not just despair, but habituation.

- Belonging as buffer: When people feel they matter, their desire for death often diminishes. Connection is protective (Joiner, 2005).

What We Can Take Away

This book isn’t just for researchers or clinicians — it’s for communities and individuals who want to understand and perhaps help.

- A better vocabulary: Instead of vague or stigmatizing phrases (“selfish,” “gave up”), we can use precise, compassionate terms like thwarted belongingness.

- Risk identification: We can ask: Does this person feel they belong? Do they feel burdensome? Have they been repeatedly exposed to pain?

- Actionable prevention: If belonging protects, then community, connection, and responsibility matter. If burdensomeness is a perception, then gently challenging it is vital.

- Humility and empathy: Models help, but human compassion is irreplaceable.

Let’s Reflect

In Why People Die by Suicide, Joiner offers not just a theory but an invitation: to see suicide not as a moral failure, but as a tragic convergence of loneliness, perceived burden, and acquired fearlessness. Understanding is not cure — but it is the beginning of prevention.

If belonging can protect, and if even a smile on the way to a bridge can matter, then perhaps we carry more power than we think to help others hold on.

Next month on Psyched For Books, we’ll explore the psychology of habits — how we form them, why we break them, and what science says about change. Bring your coffee, curiosity, and a dash of humor.

References

Chu, J., Goldblum, P., Floyd, R., & Bongar, B. (2010). The cultural theory and model of suicide. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 14(1–4), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2009.11.001

Hjelmeland, H., & Knizek, B. L. (2010). Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(1), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.74

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114

Ma, J., Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L., & Han, J. (2016). A systematic review of the predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(10), 1177–1189. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20721

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 1). Psyched for Books: How Thomas Joiner Helps Us See Suicide Differently. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psyched-for-books-thomas-joiner/