Introduction

Think back to a time you stubbed your toe, went through heartbreak, or received devastating news. Now recall a moment of pure joy — a delicious meal, a celebration, a beautiful sunset.

Which memory feels more vivid?

Chances are, the pain stands out more sharply.

This imbalance is no accident of memory; it’s a feature of the human mind. Psychological and neuroscientific research reveals that pain experiences are encoded, stored, and recalled differently than pleasurable ones. Pain — whether physical or emotional — leaves deeper cognitive and emotional traces because of how evolution shaped the brain to prioritize survival over comfort.

Our minds are not designed to make us happy; they are designed to keep us alive. And remembering pain is one of nature’s most effective survival tools.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

The Negativity Bias

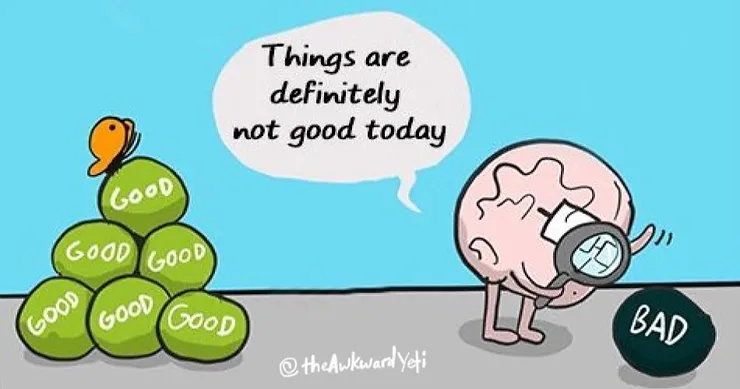

At the heart of this phenomenon lies the negativity bias, the brain’s tendency to give greater weight to negative experiences over positive ones (Baumeister et al., 2001).

From an evolutionary standpoint, this bias makes sense: missing a potential pleasure might mean lost opportunity, but missing a potential danger could mean death.

Psychologist Rick Hanson puts it succinctly: “The brain is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones.” This metaphor captures how emotional weight influences memory consolidation. Negative events trigger stronger activity in the amygdala, the brain’s emotional alarm center, which flags them as “important” for future reference.

As a result, our neural systems preferentially record painful or threatening experiences — ensuring we remember what to avoid next time.

How Pain and Pleasure Are Processed in the Brain

Pain and pleasure are processed through overlapping yet distinct neural circuits.

Both engage the limbic system — a network responsible for emotions and motivation — but the details differ significantly.

Physical pain primarily activates the somatosensory cortex, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Apkarian et al., 2005). These regions register both the sensory and emotional dimensions of pain. When emotional pain — such as rejection or loss — occurs, the same neural regions light up, which is why social and physical pain often “feel” similar (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004).

Pleasurable experiences, on the other hand, engage the mesolimbic dopamine system, particularly the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area (VTA) — circuits responsible for reward, motivation, and reinforcement (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015).

However, while pleasurable experiences activate dopamine spikes that fade quickly, painful events trigger stress hormones like cortisol and norepinephrine, which have longer-lasting effects on memory formation.

This means pain imprints more deeply and endures more stubbornly in the mind.

The Role of Memory Consolidation

When we experience something intense — a breakup, an injury, an argument — our body’s stress response kicks in. The amygdala releases neurotransmitters that signal the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center, to prioritize storing this information (McGaugh, 2004).

The message is clear: “This matters. Don’t forget it.”

Pleasurable events, by contrast, usually lack the same urgency. While they activate positive emotion, they don’t always engage the fight-or-flight system that strengthens long-term memory traces.

Interestingly, laboratory studies show that emotional arousal — whether positive or negative — enhances memory consolidation, but negative arousal tends to do so more powerfully and persistently (Kensinger, 2007). This helps explain why traumatic events can feel as vivid years later as they did the day they occurred, while even extraordinary joys fade over time.

Why Pain Feels Vivid and Why That Matters

Painful experiences often come with strong contextual cues — sights, sounds, smells, and sensations. These sensory details help encode the memory more richly.

A breakup might forever link a certain song to heartache; an accident might make you wary of a particular place.

This vividness can serve as a learning mechanism. Remembering pain helps us avoid dangerous situations and make better decisions. If touching a hot stove hurt once, the memory prevents us from doing it again.

However, this adaptive feature can turn maladaptive. In cases of chronic pain or trauma, the same mechanism that protects us can trap us. The brain continues to relive and rehearse the pain, reinforcing neural pathways that make it harder to move on (Apkarian et al., 2009). This is partly why post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) involves intrusive, involuntary recollections of distressing events — the memory of pain that refuses to fade.

Emotional Pain vs. Physical Pain

The overlap between physical and emotional pain runs deeper than metaphor.

Eisenberger and Lieberman’s (2004) groundbreaking fMRI studies revealed that social exclusion activates the same brain regions as physical pain — especially the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. In other words, being rejected “hurts” in a literal neurological sense.

This shared circuitry explains why emotional wounds — like betrayal or grief — can feel physically heavy, and why their memories linger. When emotional pain reactivates, the brain responds as if the event is happening again. This re-experiencing strengthens memory recall, keeping emotional scars fresh.

Pleasurable experiences, meanwhile, rarely require reactivation for survival. We might revisit them nostalgically, but the brain doesn’t treat them as critical information. Hence, their neural pathways weaken more quickly.

The Hedonic Asymmetry

Pleasure and pain also differ in duration.

Psychological research suggests that positive emotions have a shorter half-life — they dissipate quickly as the brain returns to baseline (Fredrickson, 2001). This phenomenon, known as hedonic adaptation, helps maintain emotional stability but also limits the endurance of pleasure.

We adapt quickly to good fortune, but slowly to suffering. Winning a prize or eating a favorite meal provides a spike of joy that soon normalizes. Pain, however, lingers — not because it feels good, but because it demands resolution.

Humans have a cognitive bias toward rumination, the repetitive thinking about negative events (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). This tendency keeps painful experiences active in working memory, prolonging their emotional life. Pleasure, in contrast, doesn’t trigger the same analytical loops. We rarely overthink happiness — we just experience it and move on.

Can We Rebalance the Memory Scales?

If pain is remembered more vividly by design, can we consciously strengthen memories of pleasure?

Research suggests yes — but it requires intention.

-

Savoring and Reflection: Studies on positive psychology show that deliberately savoring positive moments enhances memory retention (Bryant & Veroff, 2007). Taking a few extra seconds to mentally “record” joy — through attention, gratitude, or journaling — helps encode it more deeply.

-

Reframing Pain: Cognitive reappraisal — reinterpreting painful experiences in a more meaningful way — can reduce their emotional sting and change how they’re remembered (Gross & John, 2003). For instance, viewing a failure as a learning experience can rewire its emotional tone.

-

Mindfulness: Mindfulness practices strengthen the prefrontal cortex’s regulation of the amygdala, reducing the intensity of negative memory reactivation (Hölzel et al., 2011). This helps transform how we relate to painful memories rather than simply suppressing them.

-

Exposure and Integration: Therapies for trauma often use controlled exposure to help recontextualize distressing memories. By repeatedly recalling them in safe environments, the brain learns to separate the memory from the emotional overwhelm.

Through these approaches, the vividness of pain can be softened while the memory of pleasure can be consciously strengthened — bringing emotional experience into better balance.

Cultural and Personal Influences

Interestingly, culture shapes how people remember pain and pleasure.

In collectivist societies, painful memories are often interpreted through social harmony and moral growth, while in individualist cultures, they may be internalized as personal failure (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). These interpretive frameworks affect both recall and emotional impact.

Personality also matters. People high in neuroticism tend to ruminate more and recall negative experiences more vividly, whereas those high in extraversion recall more positive memories (Larsen & Ketelaar, 1989). Memory, in this sense, is as much a product of personality as of biology.

The Paradox of Painful Memory

Though unpleasant, remembering pain serves crucial psychological functions. Pain anchors meaning. Many people report that their most difficult experiences — illness, loss, rejection — led to personal growth, empathy, or resilience. Psychologists call this post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

In this paradox, the very memories we wish we could forget often define our most profound transformations. Pain may be remembered differently, but it also helps construct identity, morality, and wisdom. Pleasure makes life sweet, but pain gives it shape.

Conclusion

Our minds are sculpted by imbalance — remembering pain more vividly than pleasure is not a flaw, but a survival strategy. Yet in modern life, where threats are rarely life-or-death, this ancient bias can distort our sense of balance, making the world feel harsher than it is.

To live fully, we must learn to work with the brain’s natural asymmetry: to acknowledge pain’s lessons without allowing it to dominate memory, and to amplify joy through mindful attention.

We cannot erase the cognitive weight of pain — nor should we — but we can choose how to carry it, and what stories we build from it.

In remembering pain differently, we remember what it means to be human.

References

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D., & Zubieta, J. K. (2005). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. European Journal of Pain, 9(4), 463–484.

Apkarian, A. V., Baliki, M. N., & Geha, P. Y. (2009). Towards a theory of chronic pain. Progress in Neurobiology, 87(2), 81–97.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646–664.

Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A New Model of Positive Experience. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2004). Why rejection hurts: A common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(7), 294–300.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

Hölzel, B. K., et al. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 191(1), 36–43.

Kensinger, E. A. (2007). Negative emotion enhances memory accuracy: Behavioral and neuroimaging evidence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 213–218.

Larsen, R. J., & Ketelaar, T. (1989). Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 267–283.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

McGaugh, J. L. (2004). The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 1–28.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 16). Why We Remember Pain Differently Than Pleasure and 4 Important Ways to Establish Balance. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/pain-pleasure/