Introduction

Nostalgia is often understood as a sentimental longing for the past, typically for events or periods that one personally experienced. However, a curious variant exists: a yearning for times and places one has never lived through. This feeling—sometimes referred to as anemoia—can arise when individuals become emotionally attached to an era through stories, media, music, or artifacts, even without direct personal memories of it.

From young adults feeling a connection to the 1960s counterculture to teenagers romanticizing the 1980s via retro television shows, this form of nostalgia raises intriguing questions. How can someone miss something they never experienced? Why does this longing occur, and what psychological purpose might it serve?

Read More- Sleep and Mental Health

Defining “Nostalgia Without Memory”

The concept of nostalgia traditionally involves autobiographical memory. However, contemporary psychology acknowledges that the emotional experience of nostalgia does not require actual lived experiences. Anemoia is one label for this phenomenon, describing a longing for a past that exists primarily through imagination or secondhand accounts (Jarrett, 2023).

This kind of nostalgia can be sparked by cultural artifacts—songs, films, photographs, or fashion—that evoke a particular mood or set of values associated with a historical period. It may also emerge through stories from family members, creating an imagined connection to a time before one’s birth.

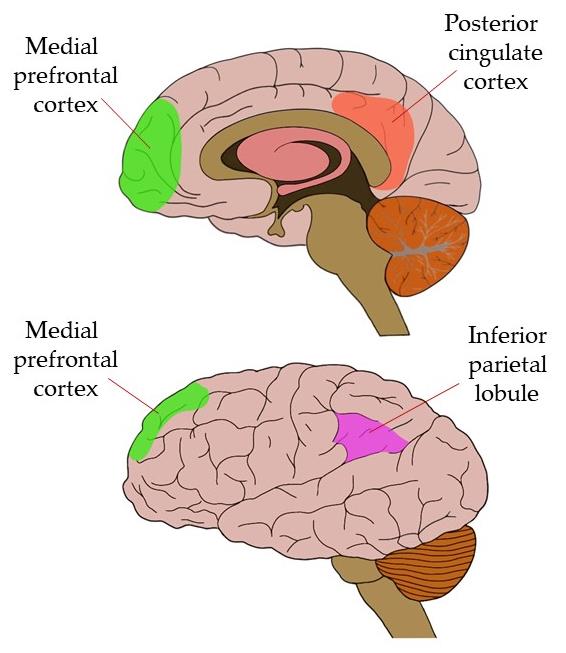

The Role of Imagination and Memory Networks

Neuroscientific research has shown that imagining events and recalling actual memories activate overlapping brain networks. The “default mode network,” in particular, supports self-referential thought, allowing individuals to mentally simulate scenarios that feel personally relevant, even if they are fictional or historical (Batcho, 2013).

Because nostalgia often serves to affirm identity and provide meaning, the mind does not strictly require authenticity of memory. If an imagined past aligns with one’s values, ideals, or desired self-image, it can evoke emotional responses as strong as those tied to real events.

Cultural Transmission of Nostalgia

Nostalgia for eras never lived in is often culturally transmitted. Parents and grandparents share stories, play music from their youth, or maintain traditions from earlier decades. Through these narratives, younger generations can inherit a “secondhand memory” of an era.

Bonnett (2016) argues that such nostalgia often serves a cultural function: it reinforces continuity across generations and provides a symbolic link to heritage. For example, an individual of Italian descent may feel a longing for mid-20th-century Italy based on family stories and cultural pride, even without ever having visited or lived there.

Media and Manufactured Memory

Popular media plays a substantial role in creating and sustaining nostalgia for unexperienced times. Television series like Mad Men and Stranger Things meticulously reconstruct the aesthetics of past decades, allowing viewers to immerse themselves in stylized representations of those eras. This “mediated nostalgia” is particularly influential when the portrayal emphasizes ideals such as community closeness, simpler living, or bold cultural change.

The 1980s, for example, have experienced a significant revival among Gen Z through music playlists, vintage clothing trends, and retro gaming. These reconstructions, while often romanticized, can create an emotional resonance powerful enough to mimic authentic nostalgia.

Psychological Benefits of Imagined Nostalgia

Even without personal memories, nostalgia—whether authentic or imagined—has been shown to offer several psychological benefits:

-

Increased Social Connectedness – Nostalgia often strengthens feelings of belonging, even if the connection is to a symbolic or imagined community (Routledge et al., 2011).

-

Self-Continuity – Imagining oneself as part of a longer historical narrative provides a sense of temporal stability, linking one’s present identity to a broader past (Shao & Wildschut, 2020).

-

Meaning-Making – Nostalgia can imbue life with meaning by connecting personal values to enduring cultural narratives or historical ideals.

These functions may help explain why people can derive comfort and inspiration from eras they have only learned about indirectly.

Risks of Romanticizing the Past

While imagined nostalgia can be enriching, it also carries potential drawbacks. Romanticized portrayals often omit historical hardships or social inequalities present in the glorified era. Viewing the past through an idealized lens can lead to unrealistic expectations about present-day life or foster dissatisfaction with contemporary society.

For instance, nostalgia for the 1950s often centers on imagery of close-knit communities and economic stability, but it can overlook systemic issues like gender inequality and racial segregation. Without a critical perspective, imagined nostalgia may perpetuate myths rather than foster nuanced historical understanding.

Generational Patterns

Different generations tend to gravitate toward different periods of imagined nostalgia. Millennials may feel drawn to the 1980s and 1990s due to their proximity in time and their presence in media during childhood. Gen Z, having grown up with digital technology, sometimes expresses nostalgia for pre-internet eras, perceiving them as more “authentic” or less overwhelming.

Globalization also shapes these patterns. Access to media from around the world allows individuals to adopt nostalgia for foreign cultural moments—such as the British Invasion in music or Japan’s 1980s tech boom—regardless of national background.

Why the Pull Is So Strong

The attraction of nostalgia for eras never lived in often lies in its emotional safety. Unlike memories tied to personal experiences, imagined nostalgia cannot be tarnished by firsthand disappointments. It exists in a mental space where the “past” is curated, stable, and controllable.

This can be especially appealing during times of uncertainty. When the present feels unstable, imagined nostalgia offers a symbolic refuge—an idealized place to anchor one’s sense of identity and hope.

Integrating Nostalgia Into Present Life

Rather than viewing this kind of nostalgia as escapism, it can be reframed as a source of inspiration. Drawing on admired aspects of an imagined past—whether fashion, music, or social ideals—can enhance creativity and enrich daily life. However, a balanced approach should acknowledge both the appealing and challenging aspects of historical realities.

By blending the positive values of a romanticized past with the opportunities of the present, individuals can use nostalgia as a tool for personal growth rather than as a retreat from reality.

Conclusion

Nostalgia for eras never lived in is a testament to the mind’s ability to emotionally connect with imagined histories. Through cultural transmission, media representation, and the shared architecture of imagination and memory, individuals can experience deep longing for times they have never personally known.

This form of nostalgia fulfills many of the same psychological roles as authentic memory-based nostalgia—fostering belonging, meaning, and self-continuity—while also offering a safe space for idealized reflection. When approached critically and creatively, it can enrich one’s identity without distorting one’s grasp on reality.

References

Batcho, K. I. (2013). Nostalgia: Retreat or support in difficult times? The American Journal of Psychology, 126(3), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.3.0355

Bonnett, A. (2016). The geography of nostalgia: Global and local perspectives on modernity and loss. Rationality and Society, 28(4), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463116672943

Jarrett, C. (2023). Anemoia: The psychology behind feeling nostalgic for a time you’ve never known. BBC Science Focus Magazine.

Routledge, C., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Juhl, J. (2011). Nostalgia as a resource for psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 638–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024292

Shao, S., & Wildschut, T. (2020). Is nostalgia a past- or future-oriented experience? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01133

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 13). Why Some People Feel Nostalgia for Eras They Never Lived In and 3 Key Benefits of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/nostalgia-for-eras-they-never-lived-in/