Introduction

We live in a world that celebrates the multitasker. Job postings list “ability to multitask” as if it’s a superpower. Friends brag about answering emails, cooking dinner, and watching Netflix simultaneously. But here’s the psychological catch: multitasking isn’t real—at least not in the way we think it is. What our brains are actually doing is something psychologists call task-switching, and it’s sneakier (and less efficient) than you might expect.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

The Myth of Multitasking

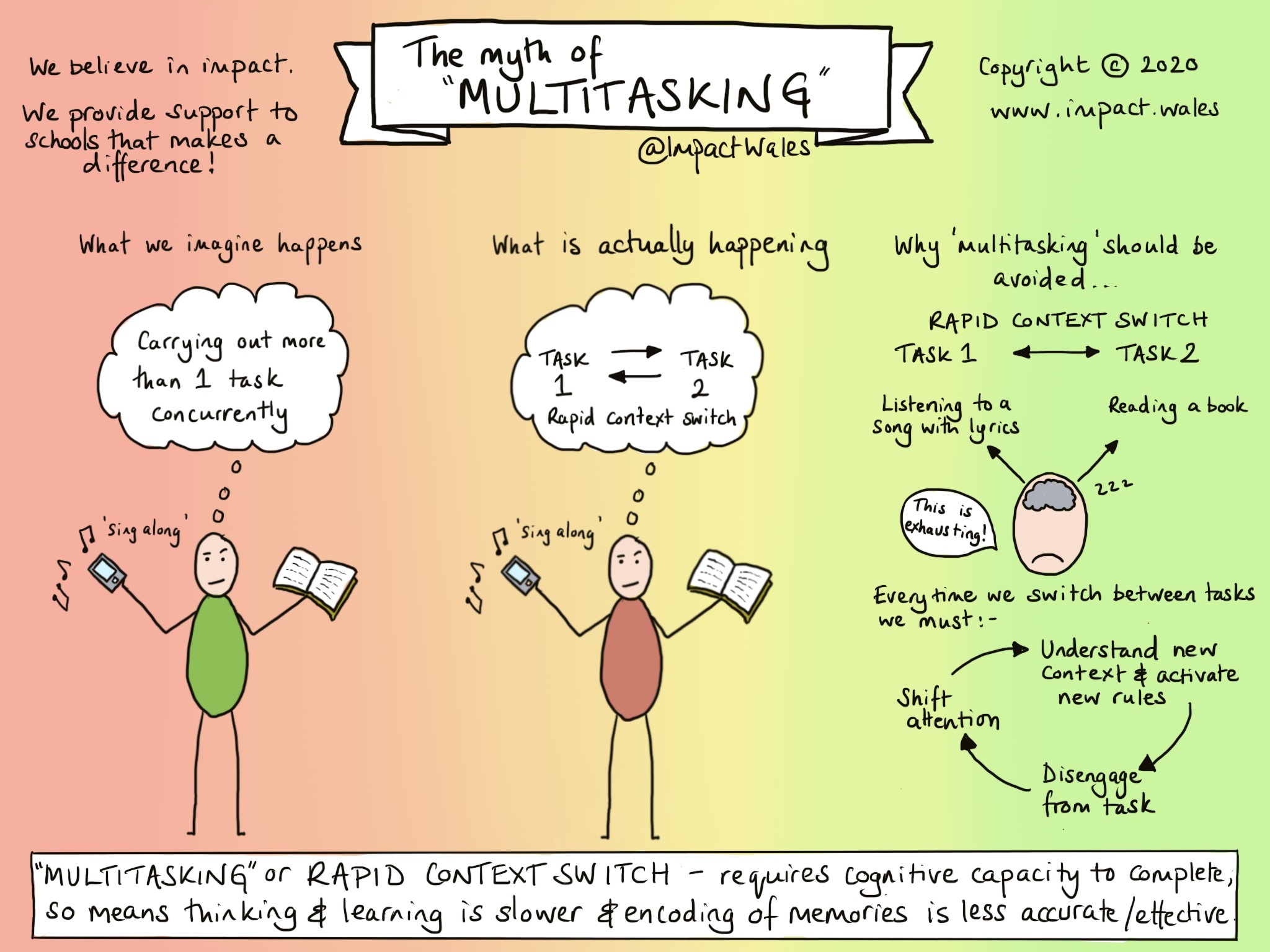

When people imagine multitasking, they usually think about handling multiple tasks at the exact same time. For example, listening to a podcast while writing a report. But unless one of those tasks is completely automatic (like chewing gum or breathing), our brains aren’t truly doing both simultaneously. Instead, they’re switching rapidly between tasks (American Psychological Association, 2006).

Think of it like a traffic light in your brain: you’re “green-lighted” for one task, then you slam the brakes, wait for the switch, and accelerate into the next. The catch? That mental stoplight isn’t instant. Each switch comes with a cognitive cost.

The “Switch Cost” Problem

Psychologists have measured this mental lag, and it’s surprisingly expensive. Research shows that task-switching reduces efficiency, increases error rates, and slows people down more than they realize (Rubenstein, Meyer, & Evans, 2001).

In fact, one study found that switching between tasks can cause productivity losses of up to 40% (American Psychological Association, 2006). Imagine writing an essay, checking Instagram every five minutes, and then wondering why it takes three hours instead of one. That’s not just “bad focus”—it’s your brain paying the switching tax.

Why the Brain Struggles

The reason we can’t multitask efficiently lies in working memory—the short-term system that holds information in our minds while we use it. Working memory has a very limited capacity (Cowan, 2010). When you jump between tasks, you’re not only losing momentum but also forcing your brain to “reload” the context of each activity.

It’s like playing a video game where every time you switch screens, you have to restart the level. No wonder it feels exhausting.

The Allure of Multitasking

If multitasking is so inefficient, why do we keep doing it? Partly because it feels good.

Researchers have found that people often believe they’re more productive when multitasking, even when their performance suffers (Sanbonmatsu et al., 2013). Multitasking provides novelty and stimulation—the brain’s equivalent of candy. Every task switch delivers a little dopamine hit, especially if one of those tasks is social media.

In other words: multitasking tricks you into thinking you’re being efficient while you’re actually draining your mental batteries.

The Digital Age

Technology has turbocharged our tendency to multitask. Between smartphones, laptops, and smartwatches buzzing with notifications, it’s almost impossible to avoid. Studies show that heavy media multitaskers (people who constantly juggle multiple screens) actually perform worse on attention-control tasks than light multitaskers (Ophir, Nass, & Wagner, 2009).

So while it feels cool to have TikTok open while writing an email with Spotify in the background, your brain is waving a tiny white flag.

The Power of Single-Tasking

Here’s the good news: humans are amazing at focusing on one thing at a time. When you give your brain a single target, it can enter what psychologists call flow state—that deeply satisfying, almost timeless zone of concentration (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Practical ways to fight the multitasking trap include:

-

Time-blocking: Dedicate chunks of time to one activity.

-

Notification diets: Limit pings, dings, and buzzes.

-

Mindful transitions: Take a short break before switching tasks, instead of bouncing chaotically.

The Takeaway

Multitasking sounds glamorous, but it’s really just inefficient task-switching in disguise. Our brains work best when they’re not pulled in a thousand directions but instead given the space to focus deeply. So next time you’re tempted to juggle five things at once, remember: you’ll finish faster, better, and happier if you just pick one.

References

American Psychological Association. (2006). Multitasking: Switching costs. APA. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/research/action/multitask

Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359277

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(37), 15583–15587. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903620106

Rubenstein, J. S., Meyer, D. E., & Evans, J. E. (2001). Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(4), 763–797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.27.4.763

Sanbonmatsu, D. M., Strayer, D. L., Medeiros-Ward, N., & Watson, J. M. (2013). Who multi-tasks and why? Multi-tasking ability, perceived multi-tasking ability, impulsivity, and sensation seeking. PloS one, 8(1), e54402. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054402

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,041 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 24). Multitasking vs Task-Switching and 3 Practical Ways to Fight It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/multitasking-vs-task-switching-and-3-practical-ways-to-fight-it/