Introduction

What sets us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom? One contender is our capacity to escape “now.” Psychologists Thomas Suddendorf and Michael Corballis (2007) coined the term mental time travel to describe our human ability to reconstruct personal experiences from the past (episodic memory) and imagine future possibilities (episodic foresight). This capacity relies on autonoetic consciousness, a self-aware state that allows individuals to re-experience and pre-experience lived and imagined events (Tulving, 2002).

Autonoetic consciousness enables individuals to mentally place themselves in different temporal frames — past or future — and is central to our cognitive uniqueness.

Read More- Main Character Syndrome

Autonoetic Consciousness and Episodic Memory

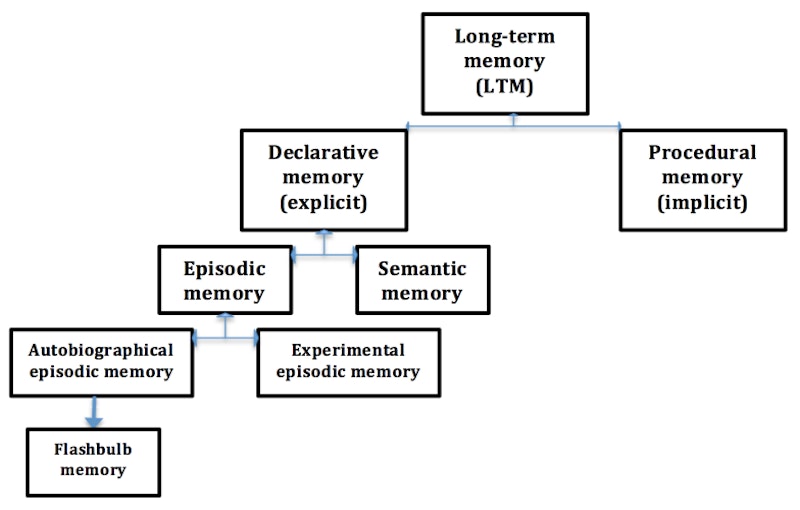

Endel Tulving (1983) distinguished between episodic memory (autobiographical events) and semantic memory (general knowledge). He proposed that episodic memory is intimately tied to autonoetic consciousness. Research with amnesic patients, such as the well-known case “K.C.,” revealed that damage to episodic memory systems also impaired the ability to imagine the future (Wheeler, Stuss, & Tulving, 1997).

Neuroimaging studies support this link: remembering the past and imagining the future activate overlapping brain regions, including the lateral parietal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (Schacter et al., 2007). This evidence supports the idea that the brain uses similar mechanisms for constructing both retrospective and prospective experiences.

Past and Future

Mental time travel into the past and the future appear to share core cognitive and neural processes. For example, D’Argembeau and Van der Linden (2004) found that personality traits like neuroticism influenced how individuals remembered past events and imagined future ones. This suggests that memory and imagination may draw on a unified mental system.

Schacter and Addis (2007) proposed the constructive episodic simulation hypothesis, which suggests that episodic memory is not just for storage, but is a flexible system that recombines elements of past experiences to simulate possible future events.

Why It’s Useful

Some of the reasons are:

1. Planning and Decision-Making

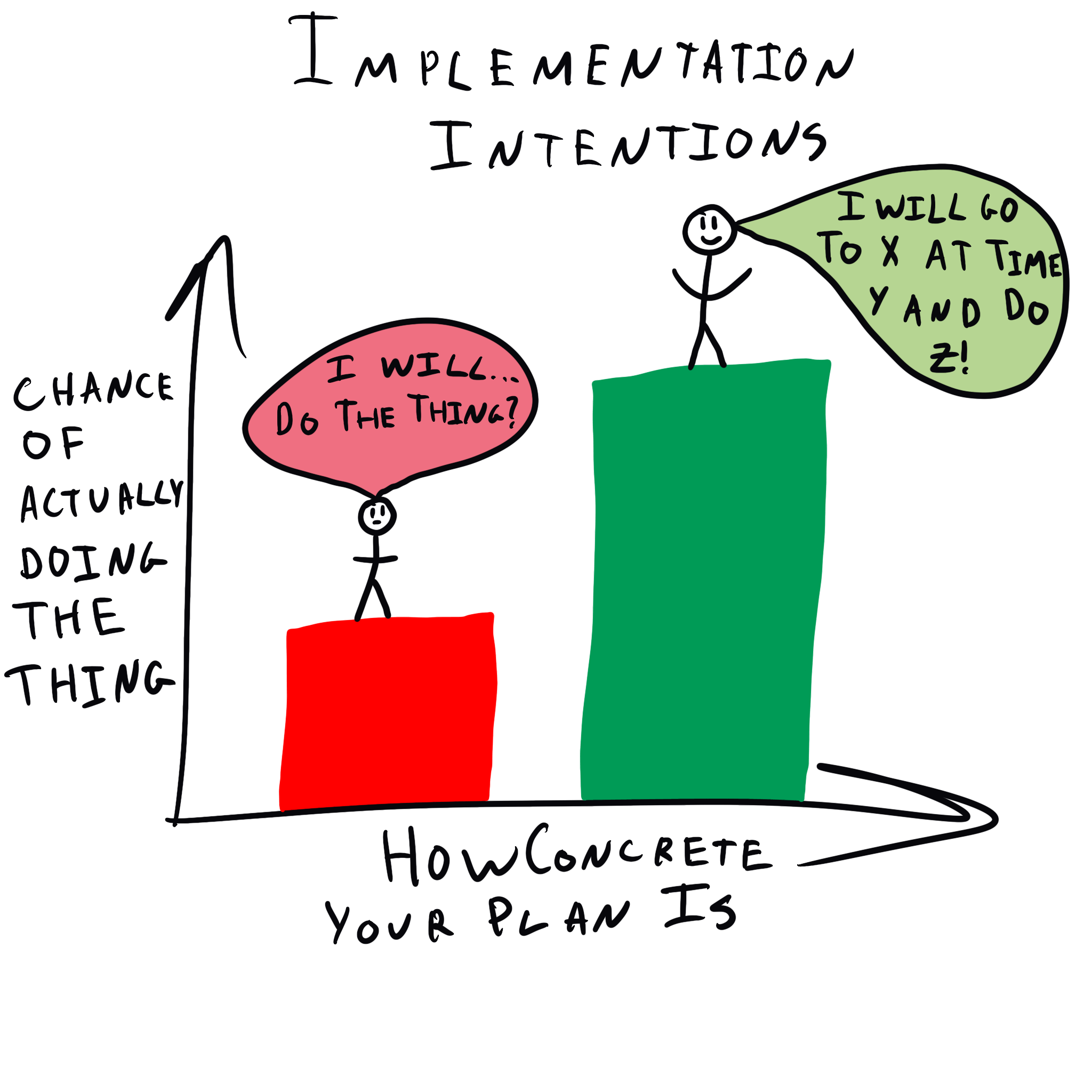

Simulating events helps with planning, but not always accurately. People often underestimate how long tasks will take — a bias known as the planning fallacy (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). This occurs because individuals focus too narrowly on idealized future outcomes while neglecting potential obstacles (Buehler, Griffin, & Ross, 1994).

2. Future-Self Connection

Research by Hershfield, Maglio, and Christensen (2023) found that individuals who first imagine their future selves and then mentally “return” to the present feel more connected to those future selves. This increases behaviors like saving money and making healthier choices. The researchers refer to this as the “temporal going-home” effect, which helps strengthen the sense of continuity between present and future identities.

3. Creativity and Problem Solving

Mental time travel also plays a key role in creativity. By replaying past experiences and simulating alternatives, individuals engage in a form of internal role-play. This flexibility enhances problem-solving, emotional regulation, and resilience (Addis, Pan, Vu, Laiser, & Schacter, 2009).

Collective Time Travel

Mental time travel isn’t limited to individual experience. It can be collective, as when societies imagine shared histories or future visions. Suddendorf and Corballis (2007) emphasized that imagined futures are not just private rehearsals — they shape everything from political campaigns to climate activism.

Imagining collective futures — such as a carbon-neutral society — can motivate prosocial behavior. When people visualize achievable, relatable futures rather than abstract utopias, they are more likely to take action (Milkman, Gromet, & Duckworth, 2021). In this way, collective mental time travel shapes culture and social policy.

Can Animals Time Travel?

Although some animals demonstrate simple planning (e.g., squirrels storing nuts), Tulving (2002) argued that only humans experience autonoetic consciousness. Corvids, primates, and rodents may anticipate future needs, but they likely do not mentally simulate events with the vividness and self-awareness of humans (Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007).

Human mental time travel involves not just foresight, but self-projection — imagining what one will feel and think in the future. That reflective dimension appears uniquely human (Tulving, 1983).

Practical Tips

Some of the practical tips are:

- Temporal Rehearsal: Mentally simulate upcoming events with specific sensory and emotional details. This improves preparation and reduces anxiety.

- Backward Time Travel: Imagine your future self first, then trace the path back to today. This “reverse-engineering” approach increases your connection to long-term goals (Hershfield et al., 2023).

- Self-Letters: Write a letter from your future self, describing what you’ve achieved and overcome. This boosts motivation and emotional clarity.

- Group Future Mapping: Create shared future scenarios with a team or community. Visioning together enhances cooperation and alignment.

Ethical and Emotional Pitfalls

Mental time travel has dark sides, too:

- Rumination: Excessive mental replay of negative past experiences can lead to depression and anxiety (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000).

- Over-idealization: Imagining overly optimistic futures can set unrealistic expectations, leading to disappointment or procrastination (Oettingen & Mayer, 2002).

- Manipulation of Shared Futures: Politicians and marketers can exploit collective mental time travel to construct emotionally charged narratives — sometimes to mislead or polarize (Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007).

Conclusion

Mental time travel weaves the past and future together in the human mind. It is central to planning, self-regulation, creativity, and social coordination. Understanding this ability allows us to use it more intentionally — to prepare for tomorrow, learn from yesterday, and envision better futures for ourselves and our communities.

We are not just creatures in time — we are creators of time.

References

Addis, D. R., Pan, L., Vu, M. A., Laiser, N., & Schacter, D. L. (2009). Constructive episodic simulation of the future and the past: Distinct subsystems of a core brain network mediate imagining and remembering. Neuropsychologia, 47(11), 2222–2238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.10.026

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. (1994). Exploring the “planning fallacy”: Why people underestimate their task completion times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.366

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2004). Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: The effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Consciousness and Cognition, 13(4), 921–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.003

Hershfield, H. E., Maglio, S. J., & Christensen, K. L. (2023). Back to the present: How direction of mental time travel affects thoughts and behavior. Working Paper, UCLA Anderson School of Management.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2021). Behavioral science interventions for climate change. Nature Human Behaviour, 5, 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01143-3

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

Oettingen, G., & Mayer, D. (2002). The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1198–1212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1198

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R., & Buckner, R. L. (2007). Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(9), 657–661. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2213

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07001975

Tulving, E. (1983). Elements of episodic memory. Oxford University Press.

Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114

Wheeler, M. A., Stuss, D. T., & Tulving, E. (1997). Toward a theory of episodic memory: The frontal lobes and autonoetic consciousness. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.331

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,045 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 30). Mind-Walks Through Time and 4 Important Practical Tips To Deal With It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/mind-walks-through-time/