Introduction

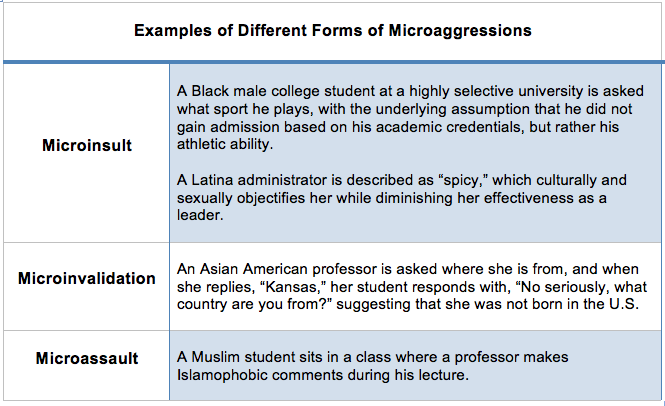

In recent years, the term microaggression has become a central concept in social psychology, capturing the subtle, often unconscious slights or insults that communicate hostility or bias toward marginalized groups (Sue et al., 2007). Yet, far less attention has been paid to the positive inverse of this phenomenon—microvalidation. Where microaggressions inflict small but cumulative emotional harm, microvalidations are the small affirmations and acts of recognition that can strengthen relationships, foster inclusion, and build trust.

Read More: Ghosting

Understanding Microvalidation

Microvalidation can be defined as a subtle, often brief act of emotional recognition or affirmation that communicates respect, understanding, or inclusion toward another person. It is the micro-level equivalent of validation—those moments when people feel seen, heard, and valued for their experiences and perspectives (Linehan, 1993).

If a microaggression might sound like “You’re so articulate—for someone from your background,” a microvalidation might sound like “I really appreciate how you expressed that idea.” It is small but meaningful—something that acknowledges competence, perspective, or emotional experience without condescension or ulterior meaning.

The psychology of validation, particularly from clinical and communication research, provides the foundation for this concept. Marsha Linehan (1993), who introduced validation as a key component of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), described it as recognizing and accepting another person’s feelings or thoughts as understandable. This doesn’t mean agreeing—it means acknowledging the subjective experience as real and coherent.

In everyday contexts, validation occurs on a micro scale. Each time someone nods empathetically during a friend’s story, mirrors a colleague’s emotion, or expresses genuine curiosity rather than judgment, they are performing microvalidations.

Why Microvalidation Matters

Microvalidations matter because relationships are built on the perception of being understood. Social psychologist Carl Rogers (1957) emphasized unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding as foundational to human connection. Modern interpersonal neuroscience backs this up—when people feel validated, their brains show reduced activity in regions associated with social pain and rejection (Eisenberger, 2012).

Moreover, microvalidations counterbalance the harm caused by microaggressions. While a single microaggression might seem trivial, research shows that repeated experiences create cumulative stress and diminished well-being (Torres et al., 2010). By contrast, repeated affirming interactions can buffer against this stress. In relationships, partners who validate each other frequently report higher satisfaction, better conflict resolution, and stronger attachment (Overall et al., 2009).

On a larger scale, microvalidation contributes to inclusive environments. In workplaces or classrooms, people who feel recognized for their perspectives are more likely to engage, innovate, and persist (Edmondson, 1999). Thus, microvalidation is not merely about kindness—it is a psychologically powerful tool for social cohesion and performance.

Forms of Microvalidation

Microvalidation can take many forms, often subtle and context-specific:

-

Active Listening Cues – Nodding, paraphrasing, or asking follow-up questions that demonstrate genuine attention.

-

Emotional Acknowledgment – Statements like “That sounds frustrating” or “I can see why you’d feel that way,” which legitimize emotion.

-

Recognition of Effort or Growth – Highlighting improvement or contribution rather than outcome, e.g., “You’ve been putting in so much effort on this.”

-

Inclusive Language – Using terms that affirm people’s identities or experiences, such as pronouns or cultural references.

-

Small Acts of Public Support – Speaking up when others are dismissed or overlooked, thereby affirming the person’s worth in group contexts.

Each of these behaviors signals to the recipient: You matter here. I see you.

Microvalidation in Romantic Relationships

In romantic or close personal relationships, microvalidations serve as daily “emotional deposits.” Relationship researcher John Gottman (1994) famously found that stable couples maintain a positive-to-negative interaction ratio of about 5:1 during conflict—meaning that small gestures of understanding and affection are crucial for relationship health.

A microvalidation might be as simple as a partner saying, “I know you’ve had a hard day—want to talk or just relax together?” This conveys emotional awareness and respect for autonomy. Over time, these microvalidations build a foundation of safety and mutual respect that can absorb stress or disagreement.

Conversely, when validation is absent, partners may feel dismissed or invisible, leading to emotional distance. Gottman’s concept of “turning toward” a partner’s bids for attention aligns closely with microvalidation—it is a small but consistent acknowledgment that sustains intimacy (Gottman & Silver, 1999).

Microvalidation in the Workplace

In professional settings, microvalidation fosters belonging and engagement. Amy Edmondson (1999) introduced the concept of psychological safety—the belief that one can express ideas or concerns without fear of ridicule or punishment. Leaders and coworkers who practice microvalidation—by listening actively, crediting contributions, or validating concerns—help create such safety.

For example, when a manager says, “That’s a valuable perspective; let’s explore it further,” they provide microvalidation that encourages participation. Conversely, dismissive behaviors (“We’ve already tried that”) function as microinvalidations, discouraging further input.

The cumulative effect of microvalidations can transform team dynamics. Studies show that teams with high psychological safety are more innovative, collaborative, and resilient to setbacks (Frazier et al., 2017).

Microvalidation and Social Identity

Microvalidation takes on heightened significance in cross-cultural or intergroup contexts. People from marginalized backgrounds often experience subtle invalidations—being interrupted, misnamed, or stereotyped—which can erode confidence and belonging.

Microvalidations in these contexts—such as using correct pronouns, acknowledging cultural knowledge, or recognizing diverse contributions—act as small reparative gestures. They communicate allyship without grandstanding.

Cultural humility plays a role here. Tervalon and Murray-García (1998) defined cultural humility as a lifelong process of self-reflection and recognition of others’ cultural identities. Microvalidation, then, can be seen as the behavioral expression of cultural humility—a practice of daily respect and acknowledgment.

Barriers to Practicing Microvalidation

Despite its simplicity, microvalidation requires mindfulness and empathy—qualities often undermined by modern communication habits. Digital interactions, for example, can strip away nonverbal cues, making validation more difficult. Miscommunication over text or email can inadvertently convey detachment or dismissal (Kaye et al., 2017).

Additionally, many people fear that validation equates to agreement. Yet validation is not endorsement; it is acknowledgment. Saying “I understand why you’d feel that way” does not mean “You’re right.” This distinction is essential for healthy dialogue, especially in diverse environments where perspectives differ.

Another barrier is emotional defensiveness. People often invalidate others because they feel threatened or misunderstood themselves. Developing self-awareness and emotional regulation—core aspects of emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995)—enables more consistent microvalidation.

Cultivating a Microvalidation Mindset

To make microvalidation a habitual practice, consider three steps:

-

Pause and Notice – Before responding, take a moment to genuinely register what the other person is expressing—emotionally and cognitively.

-

Name and Normalize – Reflect back what you observe, e.g., “That must be tough,” or “It makes sense you’d feel that way.”

-

Reinforce Value – End with a statement that affirms the person’s worth or contribution: “I really appreciate you sharing that.”

Like mindfulness, microvalidation strengthens with practice. It requires slowing down and being intentional in everyday conversations.

The Ripple Effect of Microvalidation

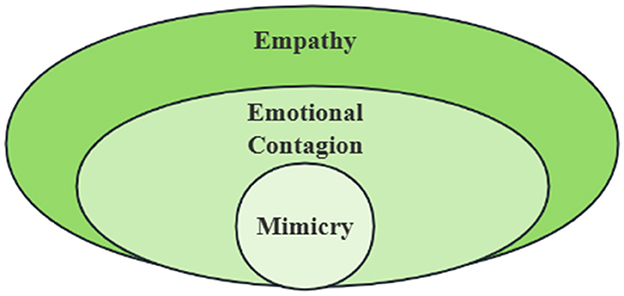

While individual acts of validation may seem insignificant, their cumulative effects can reshape relational and organizational climates. Research on emotional contagion shows that positive interpersonal behaviors tend to spread through groups (Barsade, 2002). When one person models microvalidation, others often reciprocate, creating upward emotional spirals.

In social movements or community contexts, microvalidations also build solidarity. Recognizing someone’s lived experience—without judgment or dismissal—can be deeply healing. It transforms empathy from sentiment into action.

Conclusion

Microvalidation offers a powerful yet underexplored framework for strengthening relationships and promoting inclusion. In a world increasingly dominated by digital noise, brief acts of acknowledgment—listening, affirming, recognizing effort—serve as antidotes to disconnection.

As psychology continues to highlight the harm of microaggressions, equal attention should be given to the healing power of microvalidations. They remind us that empathy, at its core, is often expressed not through grand gestures, but through consistent, mindful acts of recognition that communicate one simple truth: You matter.

References

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 644–675.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(2), 126–135.

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Psychology Press.

Gottman, J. M., & Silver, N. (1999). The seven principles for making marriage work. Crown Publishers.

Kaye, L. K., Wall, H. J., & Malone, S. A. (2017). “Turn that frown upside-down”: A contextual account of emoticon usage on different virtual platforms. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 165–175.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Overall, N. C., Fletcher, G. J. O., & Simpson, J. A. (2009). Helping each other grow: Romantic partner support, self-improvement, and relationship quality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(2), 149–163.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125.

Torres, L., Driscoll, M. W., & Burrow, A. L. (2010). Racial microaggressions and psychological functioning among highly achieving African-Americans: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(10), 1074–1099.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 2). Microvalidation and 5 Important Forms of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/microvalidation-and-5-important-forms-of-it/