Introduction

Have you ever walked through a crowd with your headphones on, dramatic music playing, and imagined yourself in the opening scene of a film? Or stared thoughtfully out a rainy window while picturing a poetic voiceover narrating your thoughts? You may have experienced what the internet has dubbed Main Character Syndrome (MCS).

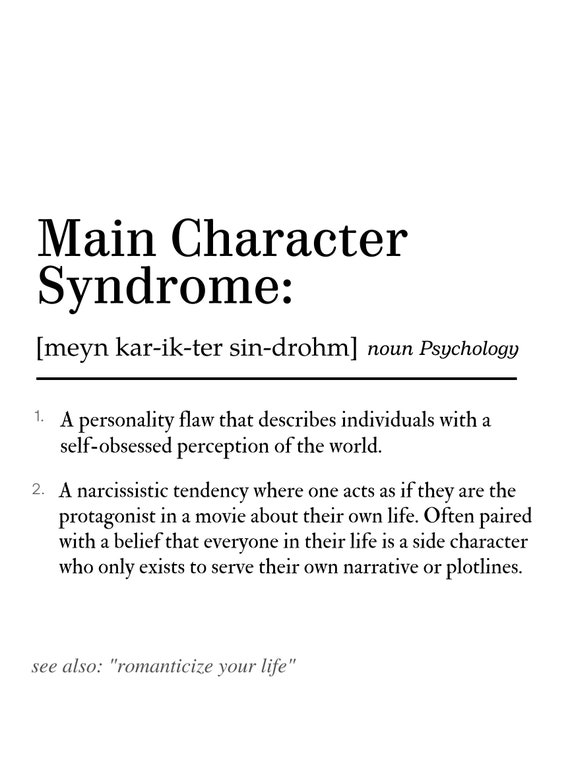

Although not a clinical diagnosis, Main Character Syndrome refers to a growing cultural phenomenon where individuals perceive themselves as protagonists in a cinematic version of their life. Popular on platforms like TikTok and Instagram, the concept has psychological roots worth exploring. Is this just harmless self-romanticizing—or is there something deeper at play?

Read More- Digital Narcissism

Egocentrism and the Center of the Story

Main Character Syndrome has its basis in egocentrism, a cognitive bias where individuals perceive the world primarily through their own perspective. Jean Piaget (1952) observed this as a developmental stage in children, though remnants of egocentric thinking persist into adulthood.

Psychologist David Elkind (1967) extended this concept with the idea of the imaginary audience—the belief, especially in adolescence, that one is constantly being observed and evaluated by others. This belief mirrors MCS closely: the assumption that our lives are interesting enough to warrant constant attention.

The Role of Narrative Identity

While the idea of being the “main character” can seem self-indulgent, it may serve a deeper psychological function. According to Dan McAdams (1993), people naturally construct a narrative identity—a coherent story that gives their life meaning and direction.

Main Character Syndrome, then, might be an informal method of shaping one’s narrative identity. It helps individuals reframe mundane events into meaningful, cinematic moments. This process can foster a sense of control, self-coherence, and even optimism.

Romanticizing Life and Mental Health

Interestingly, studies suggest that mildly unrealistic positive illusions about oneself may actually support psychological well-being. Taylor and Brown (1988) found that such illusions are associated with higher self-esteem, better relationships, and greater resilience.

Seen through this lens, MCS could act as a psychological buffer—a way to make everyday life feel more vibrant, significant, and emotionally rich.

Social Media’s Cinematic Lens

Social media has undoubtedly amplified Main Character Syndrome. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok encourage users to curate their lives visually and narratively, complete with background music, filters, and daily vlogs.

According to social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954), people evaluate their worth and abilities by comparing themselves to others. As users scroll through highlight reels of others’ lives, the pressure to create an equally compelling personal narrative increases. MCS might be a creative—and sometimes necessary—response to that pressure.

Risks and Limitations

Although MCS can serve adaptive functions, it carries potential risks. Taken to the extreme, the belief that one is always the center of the narrative may border on narcissism or entitlement. The DSM-5 outlines narcissistic traits such as grandiosity and a lack of empathy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which could emerge if MCS becomes an excuse to dismiss others’ perspectives.

Thus, self-awareness is key. Using MCS as a tool for self-expression or motivation is harmless—even helpful—but it should not come at the expense of empathy or groundedness.

Conclusion

Main Character Syndrome reflects a fascinating intersection of psychology, culture, and technology. Rooted in natural cognitive processes and amplified by social media, it offers insight into how people seek meaning, control, and identity in their daily lives.

So long as it is approached with balance and self-awareness, adopting a “main character” mindset can be more than just an internet trend—it can be a creative and emotionally intelligent way of making sense of the world.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38(4), 1025–1034.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self. Guilford Press.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. International Universities Press.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, April 16). Main Character Syndrome: Why We Crave to Feel Special in a World That Feels Ordinary. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/main-character-syndrome/

Pingback: 5 Powerful Ways Gen Z Language is Secretly Healing Their Minds - PsychUniverse

Pingback: The Psychology Behind "Delulu Thinking" and 5 Ways to Put a Healthy Spin to It - PsychUniverse

Pingback: Why Your Brain Loves Cat Videos and 4 Ways to Enjoy Them Without Getting Stuck - PsychUniverse

Pingback: The Last of Us and 5 Uniquely Insightful Aspects That Draws Us To It - PsychUniverse

Pingback: Cabeza, Corazón, Cojones and 3 Important Psychological Lessons From Alcaraz's Win - PsychUniverse

Pingback: The ‘Strong Friend’ Persona and 4 Important Strategies For Support - PsychUniverse