Introduction

In zones of conflict, words can be as powerful as weapons. In regions such as Gaza, Syria, and other sites of protracted violence, poetry, slogans, songs, and chants often function as instruments of resistance. Language of Resistance is a power tool. While tanks and missiles dominate headlines, language wields a subtler yet profound power: it preserves identity, manages trauma, and maintains hope. Through the lens of psychology, language in conflict zones is more than communication—it is a tool of resilience, coping, and social cohesion.

Scholars have noted that human beings naturally construct meaning from experiences, especially chaotic or traumatic ones (Bruner, 1990). In conflict, narratives provide coherence, reduce uncertainty, and sustain group identity. They can also shape emotions and behavior, offering pathways for both individual and collective empowerment. In Gaza, for instance, poetry and slogans serve as daily affirmations of existence and resistance, reinforcing the community’s psychological and cultural fabric.

1. Narrative as Psychological Armor

Stories are central to human cognition. Jerome Bruner (1990) argued that humans are “storytelling animals” who organize experiences into meaningful narratives. In conflict zones, narratives perform several psychological functions:

-

Coherence: Traumatic events can create chaos and confusion. Narratives provide structure, helping individuals and communities interpret and integrate difficult experiences (Neimeyer, 2001).

-

Identity Reinforcement: Stories and chants repeatedly affirm collective existence: “We are still here,” preserving the sense of continuity and belonging (Hammack, 2010).

-

Cultural Memory: Narratives preserve histories, rituals, and symbols, safeguarding culture from erasure by conflict.

A participant in a Gaza poetry initiative described the effect: “Even amidst rubble, our words rise like towers of hope” (Abu-Amsha, 2017), capturing the symbolic protective function of language as psychological armor.

2. Language and Identity

Language is a fundamental marker of group identity. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1978) emphasizes that belonging to a linguistic or cultural group enhances self-esteem and fosters solidarity. In conflict zones, language becomes a defensive and empowering tool:

-

Cultural Preservation: Oral poetry, songs, and slogans protect local traditions and dialects under threat.

-

Collective Self-Esteem: Repeated verbal affirmation of cultural pride strengthens the community’s psychological resilience.

-

Symbolic Resistance: Language signals defiance and resilience against external pressures (Feldman, 2018).

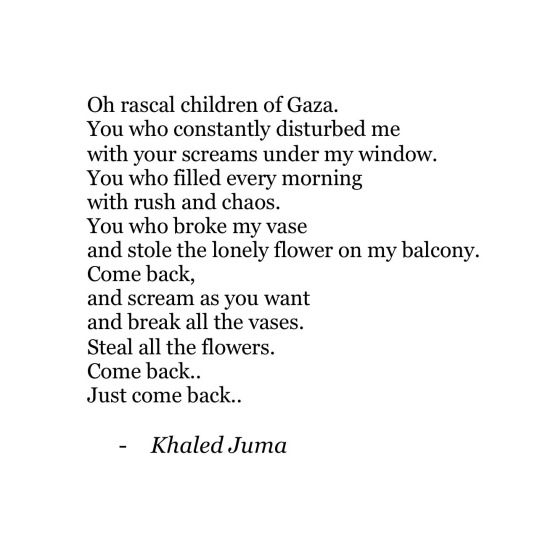

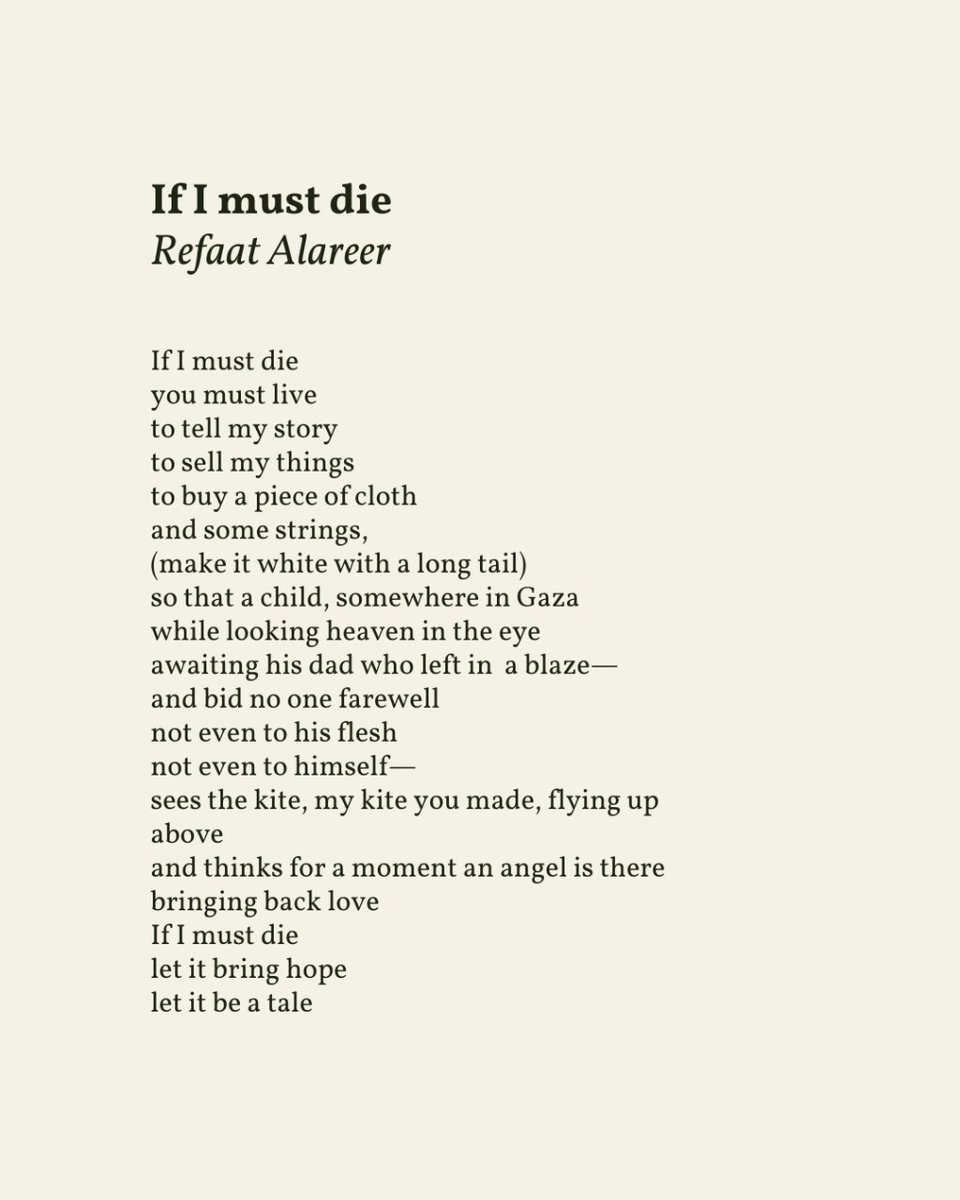

Poetry often serves as a vessel for identity and hope. For example, translated excerpts from Gaza poets read:

“In every whispered chant, we plant a seed of tomorrow” (Abu-Amsha, 2017).

Here, language is not only expressive but performative—it shapes a psychological future even amidst destruction.

3. Emotion and Catharsis

Expressive writing and oral storytelling have well-documented therapeutic benefits. Pennebaker (1997) demonstrated that writing about emotional experiences reduces stress and promotes emotional processing. In conflict, resistance language performs similar functions:

-

Channeling Grief and Fear: Slogans, songs, and poetry transform trauma into structured expression.

-

Restoring Agency: Articulating emotions through language gives individuals a sense of control over chaotic circumstances (Rotter, 1966).

-

Facilitating Emotional Release: Shared readings or chanting create collective catharsis, enhancing emotional regulation at the group level.

A study by Thabet et al. (2008) in Gaza found that participation in poetry workshops significantly reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms among children exposed to conflict, demonstrating the tangible psychological benefits of verbal resistance.

Read More: Media and Psychology

4. Words as Coping Mechanisms

When material resources and physical safety are threatened, language becomes a locus of control. Individuals and communities employ verbal strategies to maintain psychological agency:

-

Daily Affirmations: Poetry, chants, and songs serve as repeated rituals that reinforce hope and identity.

-

Symbolic Acts: Slogans painted on walls, recited in schools, or broadcast via social media signal presence and resilience.

-

Public Readings: Poetry evenings and communal storytelling create collective cohesion, reducing isolation and fostering solidarity.

These practices align with Rotter’s (1966) concept of internal locus of control: even when external circumstances are oppressive, control over one’s language fosters a sense of psychological empowerment.

5. Global Witnessing and Empathy

In the digital age, resistance language transcends local borders. Social media, hashtags, and translated poetry amplify the psychological impact beyond the immediate conflict zone:

-

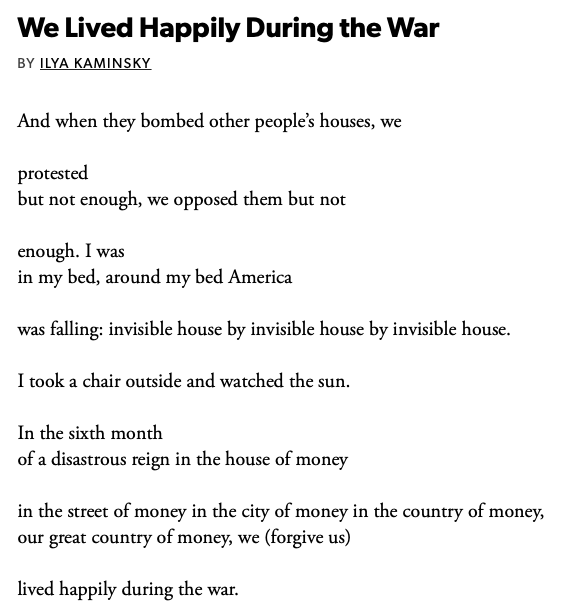

Raising Awareness: Language communicates lived experiences to global audiences, bridging geographical and cultural gaps.

-

Fostering Compassion: Exposure to resistance narratives cultivates empathy and moral engagement among international observers (Haidt, 2003).

-

Transnational Solidarity: Words facilitate psychological identification with distant others, creating virtual communities of support.

As one activist noted: “Our words travel further than missiles, touching hearts worldwide” (Ghanem, 2019). Here, language is both weaponized and humanized, serving as a tool of influence and connection.

The Double-Edged Sword of Language

Language can unite or divide. While it is a powerful medium for resilience, it also carries risks:

-

Positive Framing: Constructive, affirming language reinforces hope and group cohesion (Lakoff, 2004).

-

Negative Framing: Aggressive or demonizing slogans may escalate hostility, perpetuate cycles of violence, and provoke counter-responses.

Psychologically, the conscious use of language is crucial. Communities must balance expressions of resistance with mechanisms that avoid inflaming further conflict, demonstrating the dual nature of verbal power.

Children and Psychological Resilience

Children are particularly sensitive to conflict, but language can serve as a protective factor:

-

Processing Trauma: Participation in chants, poetry recitals, and songs helps children articulate and integrate traumatic experiences (Frankl, 1959).

-

Constructing Meaning: Verbal expression enables children to frame their experiences coherently, fostering a sense of agency.

-

Emotional Protection: Language provides a psychologically safe space for coping, enhancing resilience (Cohen & Mannarino, 2008).

In Gaza, youth poetry initiatives encourage children to narrate their experiences, channel emotions constructively, and develop a sense of collective identity despite adversity.

Conclusion

In conflict zones such as Gaza, words serve as lifelines. Language—through poetry, slogans, songs, and chants—preserves identity, channels emotions, and sustains hope. Psychological research underscores that narratives and expressive language function as coping mechanisms, reinforcing collective and individual resilience. While physical structures may be destroyed, language ensures the persistence of cultural and psychological continuity. Resistance language operates as both a shield and a beacon: it protects communities from despair while signaling survival, defiance, and the indomitable human spirit. In essence, words in conflict zones are not mere communication—they are instruments of psychological survival and markers of enduring hope.

References

Abu-Amsha, S. (2017). Voices of resilience: Poetry and identity in Gaza. Journal of Middle Eastern Cultural Studies, 12(3), 45–67.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2008). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. Guilford Press.

Feldman, N. (2018). Language as resistance: Linguistic identity in conflict zones. Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000267

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Ghanem, R. (2019). Digital poetry as a tool for social resilience. International Journal of Conflict and Communication, 5(2), 112–129.

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

Hammack, P. L. (2010). Narrative and the cultural psychology of identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(3), 222–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310362980

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t think of an elephant! Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Neimeyer, R. A. (2001). Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. American Psychological Association.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

Thabet, A. A. M., Abed, Y., & Vostanis, P. (2008). Emotional problems in Palestinian children living in a war zone: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 371(9615), 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60333-6

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, September 30). The Language of Resistance and 5 Important Psychology of Words in Conflict. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/language-of-resistance/