Introduction

We all wear social masks. We present ourselves as capable, composed, and likable. Yet beneath the surface lies a hidden realm of traits, impulses, and fears that we suppress or deny. Psychologist Carl Jung called this unseen side of the personality the shadow. Engaging with it—a process known as shadow work—can lead to greater self-awareness, emotional integration, and authenticity.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Understanding the Shadow

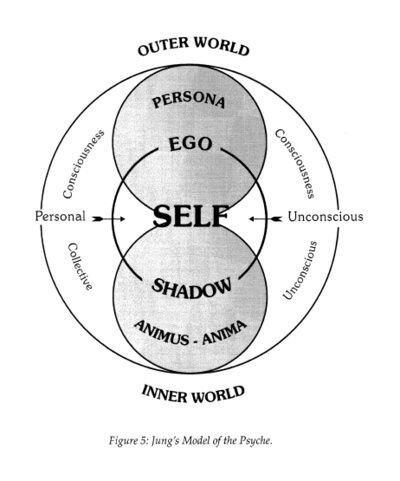

Carl Gustav Jung (1959) introduced the concept of the shadow as a component of the unconscious mind that contains traits, emotions, and drives that the conscious self, or ego, finds unacceptable. The shadow represents everything we reject about ourselves—our anger, envy, greed, or fear—but it can also hold suppressed creativity, spontaneity, and strength. Jung emphasized that “one does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious” (Jung, 1959, p. 265).

In essence, the shadow forms when we internalize societal and familial expectations about what is acceptable. As children, we learn which behaviors are rewarded and which are punished. The parts of ourselves that elicit disapproval become buried. Over time, these repressed traits do not disappear; they influence behavior from beneath consciousness, often appearing as projections or triggers.

Projection and the Mirror Effect

When we encounter traits in others that we dislike or judge, we may be seeing aspects of our own shadow reflected back to us. Jung (1959) described projection as a defense mechanism in which individuals attribute their unconscious impulses to others. For example, someone who suppresses their own ambition might view ambitious people as arrogant or selfish. This is known as the mirror effect—the world reflects what we reject internally.

Modern psychology continues to recognize projection as a central defense mechanism. According to Cramer (2015), projection allows individuals to manage internal conflict by externalizing uncomfortable emotions. Shadow work involves reclaiming these projections, recognizing that what irritates us in others often reveals something unresolved within ourselves.

Why Shadow Work Matters

Some of the ways that shadow works include:

1. Self-Awareness and Emotional Integration

Becoming aware of one’s shadow increases emotional literacy and reduces self-deception. As Jung (1963) argued, integration of the shadow is essential for individuation—the lifelong process of becoming whole. Research supports this idea: individuals who acknowledge and regulate difficult emotions exhibit greater psychological well-being (Gross & John, 2003).

2. Improved Relationships

Unacknowledged shadow material often manifests in interpersonal conflict. When we deny anger, jealousy, or vulnerability, we unconsciously project those emotions onto others. By integrating shadow elements, people reduce projection and cultivate empathy. Therapists frequently observe that clients who engage in such reflective work develop more balanced relationships (Clarke, 1992).

3. Personal Growth and Creativity

The shadow is not purely negative. It can be a reservoir of untapped potential. Jung (1959) noted that suppressed traits may contain the raw energy of creativity and innovation. When individuals embrace their repressed aspects, they often experience renewed vitality and authenticity.

4. Psychological Resilience

Facing one’s shadow fosters resilience by normalizing imperfection. Rather than striving for moral or emotional purity, individuals learn to accept their humanity. This acceptance reduces shame and promotes mental flexibility (Brown, 2010).

Risks and Ethical Considerations

While shadow work can be transformative, it is not without risks. Confronting repressed emotions can trigger distress or re-experiencing of trauma. Depth psychologists caution that unsupervised exploration may lead to emotional flooding or confusion (Stein, 1998). For individuals with a history of trauma, depression, or dissociation, shadow work should be conducted with a licensed therapist trained in psychodynamic or Jungian approaches.

Moreover, integration does not mean acting out shadow impulses without restraint. The goal is not to indulge destructive behaviors but to understand their origins and redirect their energy consciously.

How to Begin Shadow Work

Some ways to begin shadow work includes:

1. Cultivate Psychological Safety

Before exploring unconscious material, it is essential to establish grounding practices. Techniques such as deep breathing, mindfulness, and body awareness help regulate emotion and foster stability (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). A supportive environment—trusted friends, therapy, or journaling—provides containment for difficult feelings.

2. Observe Emotional Triggers

Emotional overreactions often signal the shadow at work. When a situation provokes strong feelings of anger, jealousy, or shame, ask: What part of myself is being mirrored here? Keeping a shadow journal to record triggers and responses helps reveal recurring themes.

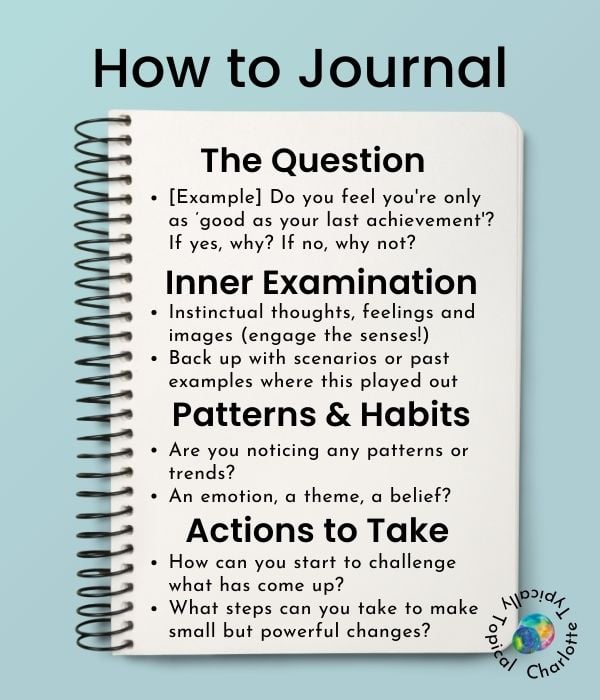

3. Reflect Through Writing

Journaling can make the unconscious conscious. Prompts include:

- What traits in others irritate or fascinate me?

- When do I feel defensive or ashamed?

- What qualities did I learn were “unacceptable” in childhood?

Writing without censorship allows hidden material to surface safely. Over time, patterns emerge that reveal underlying fears or unmet needs.

4. Dream Work and Symbolic Exploration

Jung viewed dreams as the “royal road” to the unconscious (Jung, 1963). Recording and interpreting dreams can offer symbolic insight into disowned aspects of the self. Recurring figures—such as monsters, shadows, or strangers—may represent rejected traits seeking recognition.

5. Dialogue with the Shadow

Jung developed a technique called active imagination, in which one engages in a dialogue with inner figures or emotions. This imaginative conversation helps integrate fragmented parts of the psyche. For instance, someone might visualize speaking to their anger, asking what it needs or fears. The goal is understanding, not suppression.

6. Practice Compassionate Acceptance

Self-compassion is vital. As Neff (2003) found, individuals who respond to personal flaws with kindness experience lower anxiety and depression. When exploring the shadow, treat emerging traits as misunderstood parts of yourself rather than enemies to eliminate.

7. Integrate Through Action

Integration involves behavioral change. Once shadow material is acknowledged, express it constructively. A person who suppresses assertiveness might practice setting boundaries; someone who hides their creativity might take up painting or writing. Conscious expression transforms repression into authenticity.

Contemporary Views and Critiques

While Jung’s theory remains influential, contemporary psychology critiques its lack of empirical precision. The shadow, being metaphorical, cannot be measured directly. Nonetheless, related constructs—such as defense mechanisms, repression, and self-concept incongruence—have been empirically studied. For example, research on implicit attitudes supports the idea that unconscious beliefs influence conscious behavior (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Thus, shadow work can be understood as a metaphorical framework for addressing implicit processes.

Another critique concerns the commercialization of shadow work in popular culture. Social media trends and “shadow work journals” often oversimplify a complex psychological process, reducing it to affirmation exercises. Without context or support, such practices may trivialize emotional depth or retraumatize individuals (Stein, 1998). Responsible shadow work emphasizes safety, gradual exploration, and integration into daily life.

Integrating the Shadow in Everyday Life

- Mindful Awareness – Observe emotions as they arise without judgment. Labeling emotions activates the prefrontal cortex, helping regulate reactivity (Lieberman et al., 2007).

- Embrace Paradox – Recognize that you can hold contradictory qualities: kind yet assertive, fearful yet brave. Integration means complexity, not perfection.

- Seek Balance – Use shadow insights to make balanced choices rather than swinging between extremes.

- Therapeutic Support – Jungian analysis, Internal Family Systems therapy, and depth-oriented psychotherapy provide frameworks for working with unconscious material safely.

Conclusion

Shadow work is not about purging darkness but about expanding light. It invites us to recognize that wholeness includes both the admirable and the uncomfortable aspects of the self. The shadow is not an enemy to conquer but a teacher to understand. Through gentle curiosity, honesty, and compassion, we can integrate these hidden dimensions and live with greater authenticity, creativity, and peace.

In Jung’s words, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate” (Jung, 1959, p. 287). Shadow work is the courageous act of taking back that authorship.

References

Brown, B. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden.

Clarke, J. (1992). In search of Jung: Historical and philosophical inquiries. Routledge.

Cramer, P. (2015). Understanding defense mechanisms. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(4), 523–552. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2015.43.4.523

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, dreams, reflections (A. Jaffé, Ed.). Vintage.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta.

Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S. M., Pfeifer, J. H., & Way, B. M. (2007). Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s map of the soul: An introduction. Open Court.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 21). What is Jungian Shadow and 4 Important Ways That It Matters. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/jungian-shadow/