Introduction

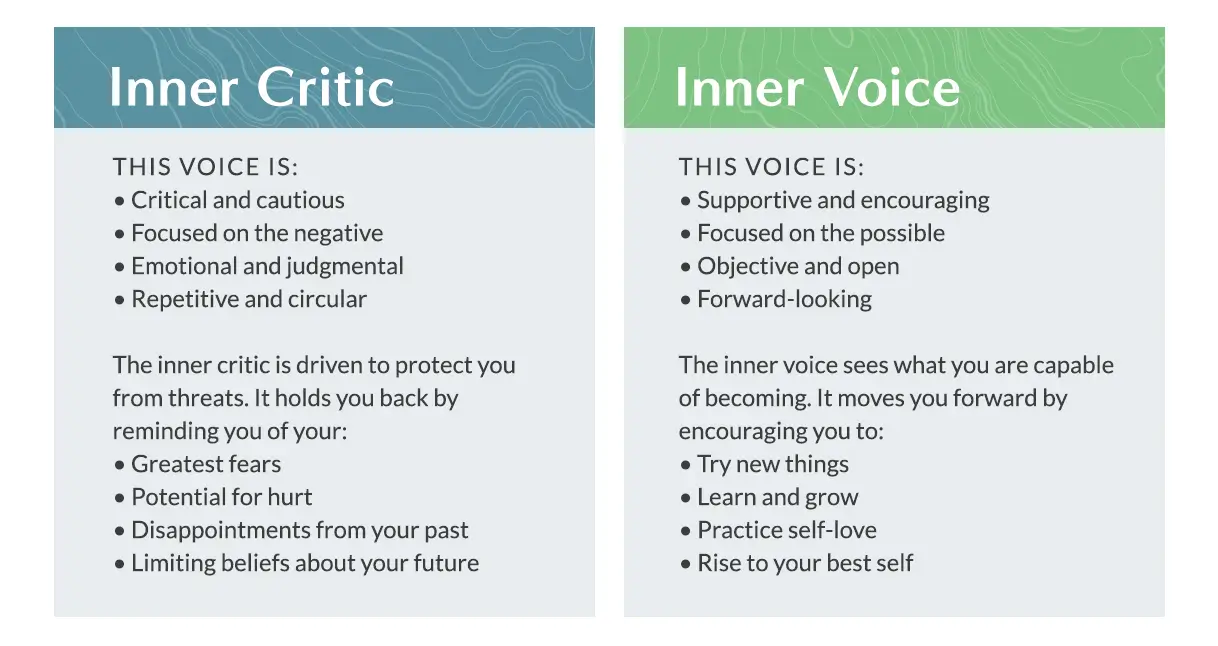

Almost everyone has an inner voice that critiques their actions. It whispers doubts, replays mistakes, and amplifies imperfections. This voice is the “inner critic,” and for many, it can be both a motivator and a source of emotional pain. While often treated as a psychological flaw, the inner critic may be better understood as a developmental artifact—a remnant of childhood experiences and evolutionary pressures.

Read More- Main Character Syndrome

What Is the Inner Critic?

The inner critic is a concept used across therapeutic modalities to describe the internalized voice that judges and shames the self. It aligns with Freud’s notion of the superego—the part of the psyche that internalizes societal norms and parental expectations (Freud, 1923). Cognitive-behavioral theorists identify the inner critic with automatic negative thoughts and cognitive distortions such as overgeneralization, catastrophizing, and labeling (Beck, 1976).

The inner critic is not inherently pathological. In moderate forms, it serves as a moral compass, encouraging self-monitoring and social conformity. However, when overactive or unchecked, it contributes to a wide range of psychological issues, including depression, anxiety, perfectionism, and low self-esteem (Gilbert & Irons, 2005).

Developmental Origins

Psychological research indicates that the inner critic often forms in early childhood. According to attachment theory, children internalize the voices and attitudes of primary caregivers, especially in environments where affection is conditional on performance or behavior (Bowlby, 1988). In such settings, children may adopt a harsh inner voice as a coping mechanism to avoid punishment or withdrawal of affection.

Authoritarian parenting styles, in particular, have been linked to higher levels of self-criticism in children. These parenting styles emphasize obedience, discipline, and high expectations, often at the expense of emotional warmth (Baumrind, 1991). Over time, children learn to preempt external criticism by developing an internal voice that mirrors these standards.

Evolutionary Perspectives

From an evolutionary standpoint, self-criticism may have conferred adaptive advantages. In early human groups, maintaining social cohesion was essential for survival. Behaviors that violated group norms could lead to ostracism, reducing one’s chances of survival and reproduction. The inner critic may have evolved as an internalized warning system, helping individuals anticipate and correct socially risky behaviors (Gilbert, 1997).

Shame, a common outcome of self-criticism, also has evolutionary roots. It functions as a social emotion that discourages actions that could damage relationships or status. By triggering withdrawal or reparative behavior, shame helps maintain group harmony (Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

Neuroscience of the Inner Critic

Neuroscientific research supports the idea that self-criticism activates the brain’s threat-detection systems. Functional MRI studies have shown that self-critical thoughts engage the amygdala and other areas associated with fear and pain processing (Longe et al., 2010). This explains why harsh internal dialogue can feel viscerally painful, triggering the same stress responses as external threats.

Chronic self-criticism can lead to elevated cortisol levels and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, contributing to anxiety, fatigue, and depression (Powers et al., 2009).

Mental Health Implications

The inner critic plays a significant role in several mental health conditions. In depression, for example, individuals often experience pervasive self-criticism, which reinforces negative self-perceptions and hopelessness (Zuroff et al., 1999). In anxiety disorders, the inner critic heightens fear of failure or social judgment. Eating disorders frequently involve a relentless internal voice that condemns the body and enforces unrealistic standards (Fairburn et al., 2003).

Self-criticism is also considered a transdiagnostic process, meaning it contributes to multiple forms of psychopathology. As such, it has become a central target in several therapeutic interventions, including Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Internal Family Systems (IFS).

Therapeutic Approaches to the Inner Critic

One of the most effective ways to address the inner critic is through self-compassion. Kristin Neff (2003) defines self-compassion as comprising self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. Research has consistently shown that self-compassion is associated with lower levels of anxiety, depression, and perfectionism, and higher levels of well-being (Neff & Germer, 2013).

Compassion-Focused Therapy, developed by Paul Gilbert, specifically targets high levels of shame and self-criticism. It encourages clients to cultivate an internal compassionate voice to counteract the harsh inner critic (Gilbert & Procter, 2006).

In Internal Family Systems therapy, the inner critic is conceptualized as a “part” of the personality that can be dialogued with and transformed. Rather than eliminating the critic, the goal is to understand its protective function and help it adopt a less extreme role (Schwartz, 2001).

Practical Strategies for Soothing the Inner Critic

Several evidence-based strategies can help individuals reduce the intensity and frequency of self-critical thoughts:

- Mindful Awareness: Noticing the presence of the inner critic without judgment.

- Cognitive Reframing: Challenging distorted thoughts and replacing them with balanced alternatives.

- Compassionate Letter Writing: Writing a letter to oneself from the perspective of a compassionate friend.

- Naming the Critic: Giving the critic a name or persona to externalize it.

- Dialoguing: Engaging in a written or imagined conversation with the critic to understand its fears and intentions.

Conclusion

The inner critic is not merely a psychological nuisance; it is a developmental and evolutionary artifact that once served protective purposes. However, in the modern world, it often becomes overactive and maladaptive. By understanding its origins and adopting strategies to transform its role, individuals can reclaim inner peace and resilience. Rather than silencing the critic entirely, the goal is to develop a more compassionate internal dialogue that promotes growth rather than shame.

References

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56-95.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509-528.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. SE, 19: 12-66.

Gilbert, P. (1997). The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(2), 113-147.

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263-325). Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353-379.

Longe, O., Maratos, F. A., Gilbert, P., Evans, G., Volker, F., Rockliff, H., & Rippon, G. (2010). Having a word with yourself: Neural correlates of self-criticism and self-reassurance. NeuroImage, 49(2), 1849-1856.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85-101.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28-44.

Powers, M. B., Laurent, J. H., Gunthert, K. C., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2009). Self-criticism and cortisol reactivity to stress in adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66(1), 53-58.

Schwartz, R. C. (2001). Internal family systems therapy. Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

Zuroff, D. C., Koestner, R., & Moskowitz, D. S. (1999). Diathesis–stress processes in negative affect: Daily self-criticism and mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(4), 568-582.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,045 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 27). The Inner Critic as a Developmental Fact and 5 Practical Ways to Deal With It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/inner-critic-as-a-developmental-fact/