Introduction

Human beings are deeply social creatures, wired to form and defend group identities. Whether based on nationality, religion, caste, sect, race, political ideology, or social movements, group identity provides a sense of belonging and purpose. However, this psychological tendency also has a darker side—it fosters division, encourages intolerance, and leads to the suppression of dissenting voices.

Throughout history, societies have curbed free speech not only through legal restrictions but also via social pressure, often escalating into mob violence. While conservatives may justify censorship in the name of tradition and national unity, progressives often rationalize it as protecting marginalized communities. Despite differing justifications, the underlying psychological mechanisms remain the same.

Read More- Tips to Improve Mental Health

What is a Group?

A group is a collection of individuals who interact, share common interests or goals, and develop a sense of belonging or identity.

A group is defined as “two or more individuals who are connected by and within social relationships” (Forsyth, 2018, p. 3).

Groups can vary in size, purpose, and structure, ranging from small informal gatherings (such as a group of friends) to large, highly organized institutions (such as political parties or corporations).

Groups play a crucial role in shaping human behavior by influencing attitudes, social norms, and decision-making processes. According to Forsyth (2018), groups provide emotional support, fulfill social needs, and contribute to the formation of personal and collective identities.

What is Identity?

Identity is “a person’s self-concept derived from individual traits, social roles, and group memberships” (Hogg, 2006, p. 111).

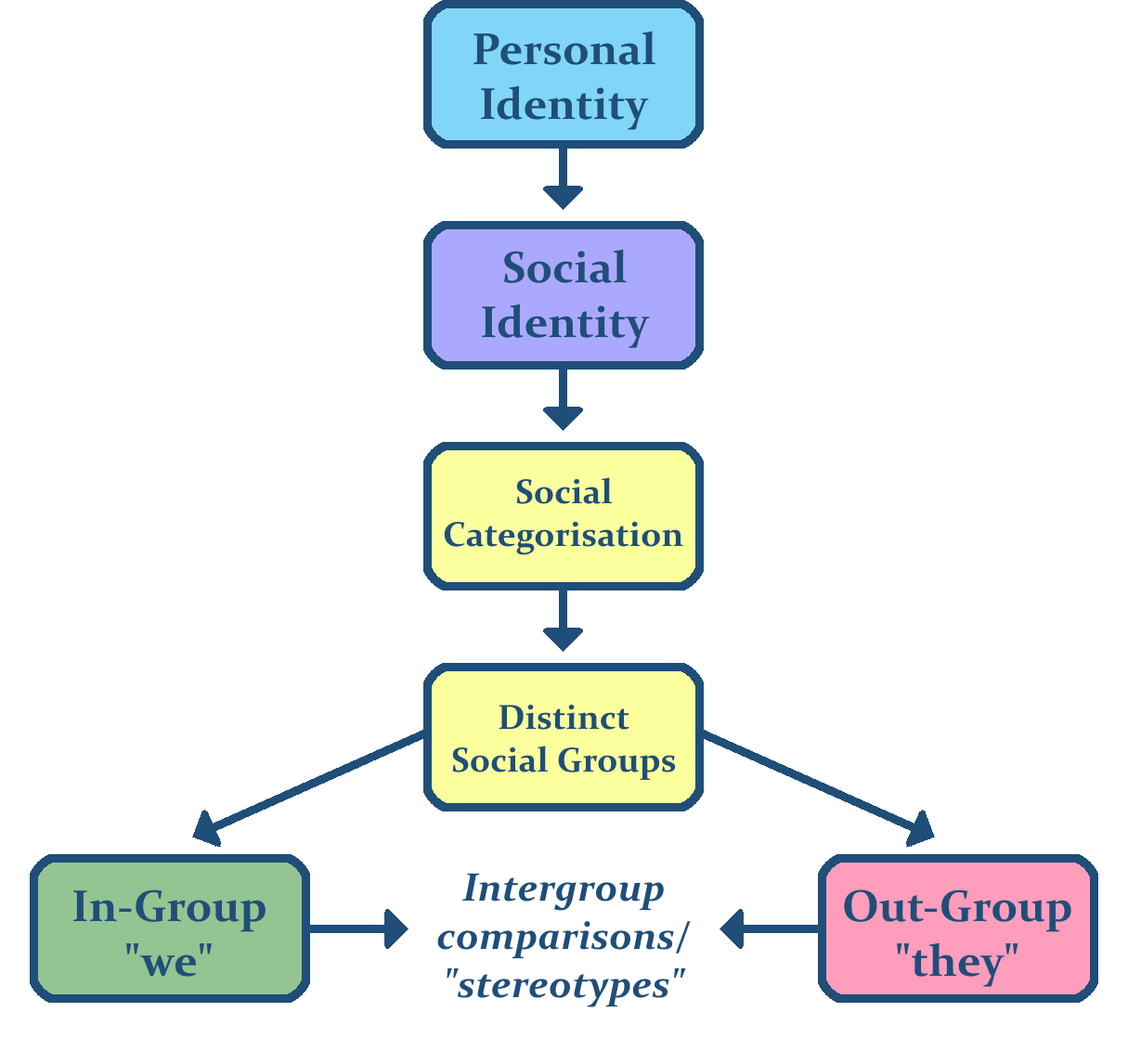

It is a complex, multidimensional concept that encompasses both personal identity—how individuals see themselves based on their unique traits and life experiences—and social identity, which relates to the groups they belong to (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

Identity is fluid and evolves over time as people encounter new experiences, cultural influences, and social interactions. Factors such as race, gender, nationality, religion, and occupation all contribute to shaping identity. Additionally, identity can influence behavior, self-esteem, and the way individuals engage with others in society.

What is Group Identity?

Group identity is the collective sense of self that individuals develop based on their membership in a particular group.

Group identity refers to “an individual’s sense of belonging to a particular group and the emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, p. 40).

It is an essential part of social identity theory, which explains how people categorize themselves and others into groups, often leading to in-group favoritism (preferring one’s own group) and out-group bias (distancing from or discriminating against others) (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Group identity can be based on various factors such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, or professional associations.

Group identity influences behavior, attitudes, and perceptions, often fostering solidarity and cooperation within the group. However, it can also contribute to social divisions and conflicts when different groups compete for resources, recognition, or power. In contemporary society, group identity plays a significant role in social movements, political activism, and cultural expression.

Psychological Mechanisms Behind It

Some of the psychological mechanisms that fuel this thinking include-

1. The “Us vs. Them” Mentality

Henri Tajfel and John Turner’s Social Identity Theory (1979) explains that people categorize themselves into groups, forming a strong attachment to their “in-group” while perceiving outsiders as threats. This creates an “us vs. them” mindset, where criticism of the group is seen as an attack on personal identity.

How This Leads to Censorship

- When an individual expresses views that contradict the dominant group narrative, they are not merely seen as offering an alternative perspective—they are perceived as betraying the group.

- The response is often swift and aggressive: deplatforming, legal action, or social ostracization.

Example- Kunal Kamra Controversy

In India, comedian Kunal Kamra became a target for censorship after his satirical critiques of the government. Right-wing nationalists labeled him “anti-national,” leading to bans on his performances and online harassment which recently escalated to mob violence. His case illustrates how in-group loyalty fuels intolerance—his critics weren’t just disagreeing with him, they saw his humor as a threat to their national identity.

On the other hand, progressives who defend Kamra’s right to free speech often use the same tactics against those they disagree with, proving that this phenomenon is not limited to one ideology.

2. Echo Chambers

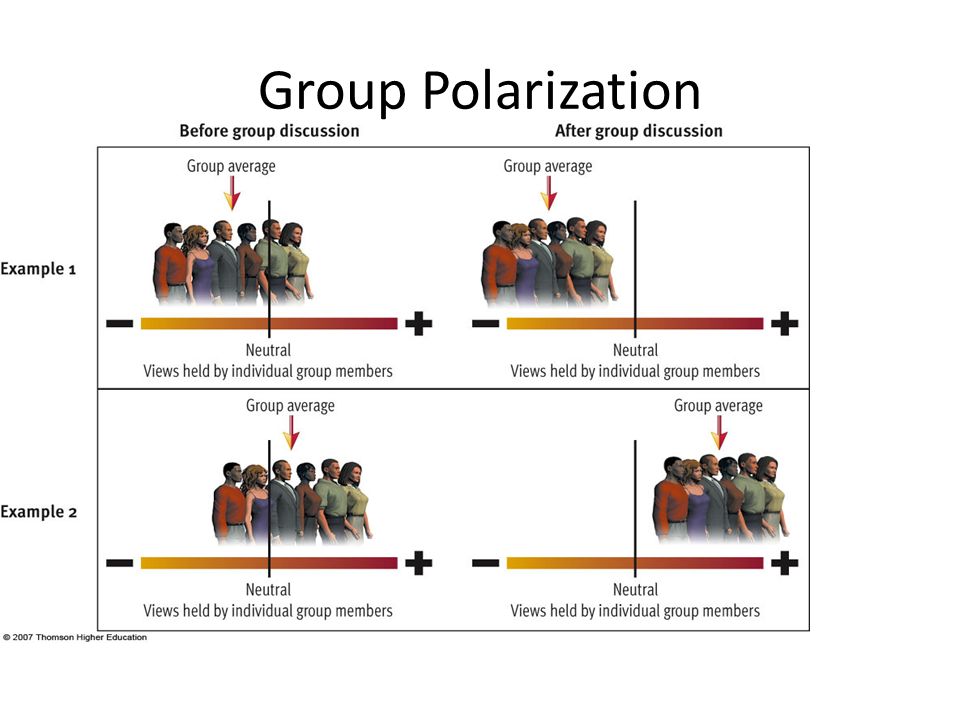

When people engage only with like-minded individuals, their beliefs become more extreme. This is known as group polarization (Sunstein, 2018). Social media amplifies this effect by creating echo chambers, where opposing viewpoints are filtered out. The result? A growing intolerance for differing opinions, making even moderate critiques seem radical or dangerous.

How This Leads to Censorship

- The more polarized a group becomes, the more it views dissent as an existential threat.

- Speech that contradicts the dominant ideology is not just debated—it is actively silenced.

Example– Cancel Culture and Deplatforming

Cancel culture, largely associated with progressive activism, is a direct result of group polarization. Public figures, authors, or comedians who express views that challenge progressive orthodoxy often face boycotts, social media bans, or career-ending backlash. While cancel culture is framed as “holding people accountable,” it often mirrors the same authoritarianism it claims to oppose.

In 2023, renowned philosopher Slavoj Žižek faced backlash and deplatforming attempts after expressing views that clashed with dominant progressive narratives, particularly on topics like gender identity and political correctness. Despite being a leftist thinker, Žižek was accused of promoting “problematic” ideas, leading to disinvitations from academic events and pressure to censor his work.

3. Maufacturing Moral Panic

People are more likely to suppress speech when they believe they are acting in the name of a greater moral cause. This is known as moral licensing—the belief that “good intentions” justify suppressing opposing views.

How This Leads to Censorship

- Right-wing groups justify censorship as “protecting national sentiment” or “defending traditional values.”

- Left-wing activists justify cancel culture as “protecting marginalized communities” from “harmful speech.”

In both cases, the act of silencing dissent is framed as a moral necessity rather than an attack on free expression.

Example– Book Bans in Schools

Throughout history, books have been banned from schools and libraries on moral grounds, with authorities claiming they contain inappropriate or harmful content. For example, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee has been frequently challenged due to its discussions of racism and sexual assault. More recently, books addressing LGBTQ+ themes, such as Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, have been removed from school libraries in certain regions, with proponents arguing they are inappropriate for young readers.

4. Groupthink

Groupthink (Janis, 1972) occurs when a group prioritizes harmony over critical thinking. In such environments:

- Individuals suppress their own doubts to avoid conflict.

- Dissenters are punished or excluded.

How This Leads to Censorship

- In political or activist circles, questioning the dominant narrative is risky.

- Individuals self-censor out of fear of backlash, leading to ideological conformity.

Example– Self-Censorship in Academia and Media

In 2019, the University of Cambridge rescinded a visiting fellowship offer to Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson after faculty and student backlash over his views on gender identity and political correctness. The university cited its commitment to inclusivity as the reason for the withdrawal.

5. Deindividuation and Mob Mentality

When people act as part of a crowd, they lose their sense of personal responsibility. This phenomenon, known as deindividuation, explains why-

- Online mobs engage in harassment and mass reporting.

- Protesters sometimes resort to violence when emotions run high.

How This Leads to Censorship

- In digital spaces, collective outrage leads to mass deplatforming of individuals.

- In physical spaces, mob violence can be used to silence critics.

Example– Online Harassment of Public Figures

Algerian Olympic boxer Imane Khelif faced intense online harassment after being disqualified from the 2023 Women’s World Boxing Championships due to gender eligibility rules. The backlash escalated when Donald Trump falsely claimed she was transgender, sparking attacks from right-wing trolls accusing her of unfair competition. At the same time, left-wing activists criticized her for not openly supporting transgender inclusion, leaving her caught between both sides.

A Psychological Solution to Group Conflict

One of the most famous studies on group conflict is the Robbers Cave Experiment (1954) by Muzafer Sherif. This study provides key insights into how group-based divisions develop—and more importantly, how they can be resolved.

How Division Escalates

Sherif took a group of 22 boys and divided them into two teams at a summer camp. Without any initial hostility, the two groups (the “Eagles” and the “Rattlers”) quickly developed strong in-group loyalty and out-group hostility. They:

- Created group names, flags, and traditions.

- Developed stereotypes about the other group (“They cheat,” “They’re weak”).

- Engaged in direct conflict, including verbal and physical aggression.

This experiment mirrors real-world political and ideological divisions—where groups form, develop loyalty, and eventually see the opposition as “the enemy.”

Superordinate Goals

Sherif found that mere interaction between the groups did not reduce hostility. Instead, conflict only decreased when the two groups were forced to cooperate on shared goals—called superordinate goals.

For example, when the boys had to work together to fix a broken water supply or pull a truck out of the mud, they gradually stopped seeing each other as enemies and started cooperating.

Applying This to Modern Conflicts

If group divisions in politics, religion, and social movements are driven by the same psychological forces seen in the Robbers Cave experiment, then the solution must also involve shared goals that require cooperation.

- Common Challenges Over Ideological Battles: Instead of focusing on ideological purity, groups with opposing views should work on practical issues that benefit everyone. Example: Political parties collaborating on infrastructure projects instead of ideological disputes.

- Encouraging Inter-Group Collaboration: Instead of isolating people into ideological communities, fostering interaction in mixed environments can reduce polarization. Example: Public forums where individuals from different backgrounds work together on community issues.

- Media and Social Platforms Promoting Shared Interests: Instead of algorithms that reinforce division, social media platforms could prioritize content that highlights common goals rather than emphasizing conflict. Example: Platforms promoting dialogue between conservatives and liberals on environmental policies rather than pushing divisive headlines.

Conclusion

The psychology behind group identity explains why societies become deeply polarized and why suppression of dissent—whether through censorship, cancel culture, or mob violence—is so common. The “us vs. them” mindset, fueled by in-group loyalty, moral justification, and group polarization, leads to hostility and ideological warfare.

However, the Robbers Cave Experiment provides a crucial insight: conflict is not inevitable. When groups are given shared challenges that require cooperation, divisions start to break down.

Rather than focusing on ideological battles, society must shift toward shared problem-solving—where people with differing perspectives work together toward common goals. This approach doesn’t just reduce division; it builds a more cooperative and functional society.

In a world increasingly driven by polarization, the question is not just “How do we stop conflict?” but “How do we create environments where cooperation becomes necessary?” The answer lies in restructuring our social, political, and digital spaces to prioritize unity over division.

References

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes. Houghton Mifflin.

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W. R., & Sherif, C. W. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment. University Book Exchange.

Sunstein, C. R. (2018). #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Swarthmore Phoenix. (2023, March 2). Žižek has lost the plot. Swarthmore Phoenix. Retrieved from https://swarthmorephoenix.com/2023/03/02/zizek-has-lost-the-plot/

The Guardian. (2019, March 20). Cambridge University rescinds Jordan Peterson’s visiting fellowship. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/mar/20/cambridge-university-rescinds-jordan-peterson-invitation

The Print. (2025, March 19). Boxing champion Khelif targets second Olympic gold in LA. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/sport/olympics-boxing-champion-khelif-targets-second-olympic-gold-in-la/2554250/

Forsyth, D. R. (2018). Group Dynamics (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,045 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, March 31). Group Identity and 5 Powerful Ways It Is Suppressing Intellectual Growth. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/group-identity/

Pingback: 6 Psychological Reasons Gen Z Slang Feels Like an Inside Joke - PsychUniverse