Introduction

You just chose to read this article. Or did you? Was that really your decision, or was it neurons, chemicals, and your past dragging you here like a cosmic puppet on a string? This profound question sits at the core of the age-old debate about free will. Are we truly in control of our decisions, or is free will just a comforting illusion? In his book Determined, neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky argues that free will is, in fact, a mirage. As he boldly puts it, “Free will is an illusion. Period.” (Sapolsky, 2023). This claim forces us to consider a world where our actions, thoughts, and choices may not be as freely made as we think. Rather, they might be the result of deep biological, psychological, and environmental forces beyond our conscious control.

Read More- Stress and Mental Health

What is Free Will?

Free will is the ability to make choices that are not determined by external forces or prior causes. It is the concept that individuals have the power to act according to their own desires, preferences, and reasoning, independent of factors like genetics, environment, or social conditioning. In essence, free will suggests that we have control over our actions and decisions, and are responsible for the outcomes of those choices. Philosophers and scientists continue to debate whether true free will exists or whether our decisions are influenced by forces beyond our conscious control.

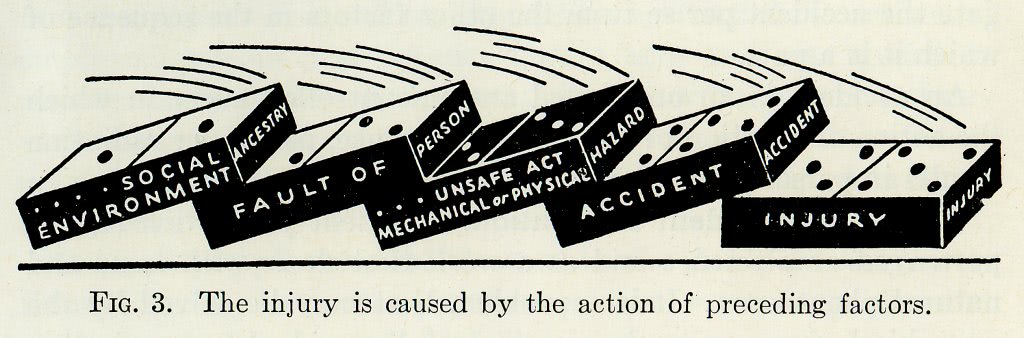

The Domino Theory of Decision-Making

According to Sapolsky, every decision you make—whether it’s that impulsive choice to eat pizza, sending a breakup text, or having an existential crisis—can be traced back to a series of prior causes. These causes include not only your past experiences but also genetic predispositions, hormonal fluctuations, and even your environment at any given moment. Sapolsky explains that our lives can be viewed as a gigantic Rube Goldberg machine, where the simplest actions are the inevitable results of complex chains of events.

Here’s the chain of events that lead to one of your decisions

- Genetic Influence: Your DNA is the starting point, coding for traits like temperament and predisposition toward certain behaviors.

- Environmental Factors: Your childhood experiences, social upbringing, and even the weather on a given day shape your behavior.

- Current Circumstances: Your emotional state, hormone levels, and external pressures—like deadlines or arguments—affect how you respond to a situation.

- The Decision: Based on all these factors, your brain decides, and you experience the illusion of making a “free” choice.

Sapolsky’s argument is that we never truly had a choice. Our brain is simply following the inevitable path laid out by these prior influences. The decisions we think we make freely are, in fact, a product of this underlying causality.

Neuroscience Backs It Up

The idea that our decisions are predetermined finds support in neuroscience. One of the most famous experiments to challenge the notion of free will is Benjamin Libet’s 1985 study. Libet discovered that the brain begins to prepare for movement before a person is consciously aware of their decision to act. This means that, on a neurological level, our brains are making decisions before we consciously “decide” to follow through with them.

Building on this, Haynes et al. (2008) used fMRI technology to predict people’s choices up to 7 seconds before they made them. In other words, our choices may be predetermined by our brain’s neural activity, even before we become consciously aware of them. The growing understanding that factors like trauma, hormonal changes, addiction, and even gut bacteria influence our behavior only adds fuel to the fire. These influences act like hidden puppeteers, pulling strings behind the scenes and shaping our actions in ways we may not fully understand or control.

Moral Responsibility Without Free Will?

If we don’t have free will, what happens to the concept of moral responsibility? Should we still hold people accountable for their actions? Sapolsky offers an intriguing perspective. Instead of focusing on moral judgments like “How evil is this person?” he suggests we should ask, “What led them to this point, and how can we prevent others from following the same path?”

This shift in thinking could lead to a more compassionate justice system. If individuals are not fully in control of their actions, punishment might not be the most effective solution. Instead, we could focus on rehabilitation, prevention, and addressing the root causes of behavior—such as mental illness, addiction, or trauma. The focus would shift from retribution to understanding and healing, offering a more scientifically grounded approach to justice.

But Compatibilists Say: Chill, You Still Have Will

Despite Sapolsky’s hard determinism, not everyone agrees that free will is an illusion. Enter the compatibilists, who argue that free will and determinism can coexist. According to compatibilism, even though our choices are influenced by factors like our genetics, environment, and past experiences, we can still act freely as long as we’re acting in accordance with our internal values and desires.

Imagine this: You’re in a self-driving car that’s programmed to take you to a specific destination. Although the car follows a predetermined path, you chose the destination. According to compatibilists, this is a reasonable analogy for human decision-making. Even though our decisions are shaped by external factors, we can still be said to be making free choices when they align with our personal goals and values. The key idea is that freedom is not about absolute control over every factor, but about acting in line with our desires and reasoning.

Free Will Feels Real (Even If It’s Not)

While Sapolsky’s argument might sound a bit unsettling, it’s important to recognize that the sense of free will is still psychologically significant. Even if free will is an illusion on a metaphysical level, believing we have the ability to choose has important effects on our behavior. Research shows that individuals who believe they have control over their lives tend to experience higher levels of motivation, better health outcomes, and even greater longevity.

For instance:

- Increased Motivation: Believing that you can influence outcomes encourages effort and persistence.

- Better Health: People who feel they have control over their health tend to make healthier choices, like exercising and eating well.

- Longer Life: Studies suggest that a sense of personal agency is linked to greater life expectancy.

It seems that the belief in free will, even if it’s an illusion, may have been naturally selected because it helps us navigate life more effectively. The illusion of choice, it turns out, has evolutionary value.

What About AI?

As artificial intelligence continues to develop, we’re faced with a fascinating question: Does AI have free will? Currently, most experts argue that AI does not possess free will because it lacks consciousness or intrinsic motivation. AI systems make decisions based on algorithms and data inputs, but they don’t have a sense of self or internal desires that guide their actions.

However, as AI becomes more advanced, we may find ourselves grappling with deeper ethical questions about whether machines could ever be considered moral agents. If AI systems begin making decisions independently, should they be held accountable for their actions? And if they can make decisions based on their “programming,” is that the same as exercising free will?

No Free Will? No Problem

Whether or not free will truly exists, recognizing the forces that shape our behavior can lead to greater empathy and understanding. Instead of holding rigidly to the idea that we are solely responsible for our actions, we can embrace the complexities of human behavior and appreciate the myriad influences that contribute to our decisions. Acknowledging the role of biology, upbringing, and environment can lead to a more compassionate, just, and humane society.

So, while you may blame your genes, your parents, or your 9th-grade math teacher for who you’ve become, remember to thank them too. After all, they helped shape the person you are today—and hey, you’re pretty cool.

References

Frankfurt, H. G. (1969). Alternate possibilities and moral responsibility. The Journal of Philosophy, 66(23), 829–839.

Haynes, J. D., et al. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), 543–545.

Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1985). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). Brain, 106(3), 623–642.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2023). Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will. Penguin Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, April 29). Does Free Will Exist? Understand the 4 Domino Events That Lead to Decision Making. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/free-will/