For much of the 20th century, childhood success was measured by intelligence quotient (IQ), academic achievement, and behavioral compliance. Today, psychology paints a broader and more nuanced picture. Emotional Intelligence (EI)—the ability to recognize, understand, manage, and respond to emotions effectively—is now recognized as a core predictor of mental health, relationship quality, academic success, and long-term well-being.

Children with strong emotional intelligence are not simply “well-behaved” or “emotionally sensitive.” They are better equipped to cope with stress, resolve conflicts, regulate frustration, and navigate social complexity. Importantly, emotional intelligence is not a fixed trait. It is a skill set that develops over time and can be intentionally nurtured.

Read More: Emotional Granularity

What Is Emotional Intelligence?

Emotional intelligence refers to a set of interrelated abilities involving emotions. According to Salovey and Mayer (1990), EI includes:

- Emotional awareness – recognizing one’s own emotions

- Emotional understanding – knowing why emotions occur

- Emotional regulation – managing emotions effectively

- Empathy – recognizing emotions in others

- Social skills – using emotional information to guide interactions

In children, these abilities unfold gradually and are deeply shaped by caregiving environments, social experiences, and modeling.

Why Emotional Intelligence Matters in Childhood

Research consistently shows that emotional intelligence predicts outcomes beyond academic intelligence alone.

Children with higher EI tend to:

- show better peer relationships

- exhibit fewer behavioral problems

- cope more effectively with stress

- demonstrate stronger academic engagement

- show lower risk of anxiety and depression

Longitudinal studies suggest that emotional competence in early childhood predicts mental health and relationship quality well into adulthood (Denham et al., 2012).

In contrast, difficulties with emotional regulation are associated with:

- aggression

- withdrawal

- anxiety

- academic disengagement

- peer rejection

EI serves as a foundation for resilience and adaptive functioning.

1. Emotional Intelligence Is Learned Through Relationships

Children are not born knowing how to manage emotions. They learn primarily through co-regulation—the process by which caregivers help children understand and soothe emotional states before they can do so independently.

When caregivers:

- acknowledge emotions

- respond with calm presence

- provide language for feelings

- model regulation

children internalize these skills over time.

This aligns with attachment theory, which emphasizes that emotionally responsive caregiving supports secure attachment and emotional development (Bowlby, 1988).

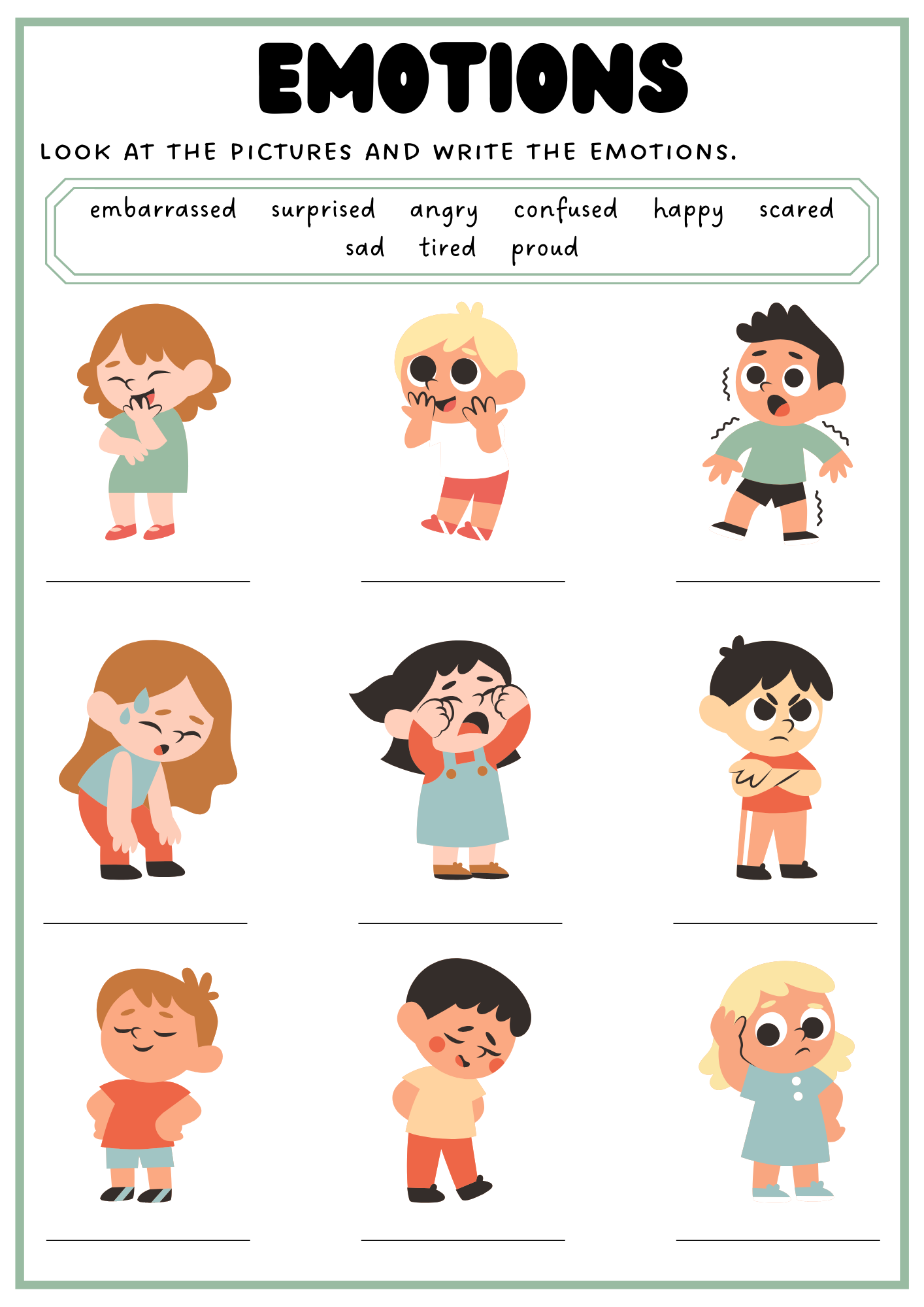

2. Emotional Awareness

One of the earliest components of emotional intelligence is emotion labeling—the ability to identify and name feelings.

Research shows that when adults help children label emotions:

- emotional intensity decreases

- regulation improves

- problem-solving increases

Lieberman et al. (2007) demonstrated that naming emotions reduces amygdala activation and increases prefrontal activity—supporting emotional regulation at the neural level.

Practical strategies include:

- naming emotions in everyday situations

- validating feelings without judgment

- using emotion-rich language

Example:

“You’re feeling frustrated because the blocks won’t stay up.”

3. Emotional Validation vs. Emotional Control

A common misconception is that teaching emotional intelligence means suppressing emotions. In reality, validation precedes regulation.

Validation means acknowledging emotions without necessarily approving behavior.

Example:

“I understand you’re angry. Hitting is not okay.”

Research shows that children whose emotions are validated develop:

- better emotional clarity

- stronger regulation skills

- greater trust in caregivers

Invalidation (“Stop crying,” “You’re fine”) may unintentionally teach children to distrust their emotional experiences.

4. Teaching Emotional Regulation Skills

Emotional regulation involves managing emotional responses in adaptive ways. This skill develops gradually and requires repeated practice.

Evidence-based regulation strategies include (Gottman et al., 1997):

- Breathing and Physiological Regulation: Slow breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, reducing stress arousal.

- Problem-Solving Skills: Helping children identify solutions builds agency and reduces emotional overwhelm.

- Delayed Response: Teaching children to pause before reacting improves impulse control.

- Emotional Coaching: Guiding children through emotional experiences rather than removing distress strengthens coping ability

5. The Role of Modeling

Children learn emotional intelligence less from instruction and more from observation.

Caregivers who:

- manage frustration constructively

- apologize when overwhelmed

- express emotions appropriately

- repair conflicts

provide powerful templates for emotional behavior.

Research consistently shows that parental emotional regulation predicts children’s regulation more strongly than verbal teaching alone.

6. Empathy Development in Children

Empathy—the ability to understand and share another’s emotional state—is a cornerstone of emotional intelligence.

Empathy develops through:

- secure attachment

- perspective-taking experiences

- exposure to diverse emotional situations

Storytelling, reading fiction, and discussing characters’ feelings enhance empathic skills. Hoffman (2000) emphasized that empathy grows through guided reflection on others’ experiences.

7. Emotional Intelligence in School Settings

Schools play a crucial role in emotional development. Social-emotional learning (SEL) programs teach:

- emotion recognition

- conflict resolution

- self-regulation

- cooperation

Meta-analyses show that SEL programs improve:

- academic performance

- behavior

- emotional well-being

- peer relationships (Durlak et al., 2011)

Importantly, these benefits persist over time.

8. Cultural and Individual Differences

Emotional expression varies across cultures. Emotional intelligence does not mean expressing emotions identically—it means responding appropriately within cultural and relational contexts.

Effective EI-building respects:

- cultural norms

- temperament differences

- individual sensitivity

Some children are naturally more emotionally intense or reserved. EI strategies should be tailored—not standardized.

When Emotional Intelligence Development Is Challenging

Children with:

- neurodevelopmental differences

- trauma histories

- anxiety disorders

- attachment disruptions

may require additional support.

In such cases, interventions like play therapy, parent coaching, and trauma-informed approaches support emotional development more effectively than discipline alone.

Long-Term Benefits of Emotional Intelligence

Children who develop strong emotional intelligence are more likely to:

- form healthy relationships

- manage stress effectively

- resolve conflicts constructively

- maintain mental health

- demonstrate leadership and cooperation

EI does not eliminate challenges—but it equips children to face them with flexibility and resilience.

Conclusion

Building emotional intelligence in children is not about eliminating negative emotions or enforcing constant calm. It is about teaching children to understand their inner world, regulate emotional responses, and connect meaningfully with others.

Emotional intelligence grows through relationships, modeling, validation, and practice. When adults respond to children’s emotions with curiosity rather than control, they lay the groundwork for lifelong emotional health.

In a world of increasing complexity, emotional intelligence is not optional—it is essential.

References

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development.

Denham, S. A., et al. (2012). Social-emotional learning in early childhood. Child Development.

Durlak, J. A., et al. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning. Child Development.

Gottman, J. M., et al. (1997). Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Journal of Family Psychology.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and Moral Development.

Lieberman, M. D., et al. (2007). Putting feelings into words. Psychological Science.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 18). 8 Important Ways to Build Emotional Intelligence in Children. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/emotional-intelligence-in-children/