Introduction

It’s early morning. You sit down at your desk. Your to-do list stares at you like a monster. And you do the natural thing: you check your email… again.

But productivity gurus (and apparently Mark Twain) suggest a different approach:

Eat the frog.

No, not literally. “Eating the frog” means doing your hardest, most important task first thing in the day—before your energy runs out or excuses take over. The term was popularized by Brian Tracy in his book Eat That Frog! (2001), based on a quote often attributed to Twain:

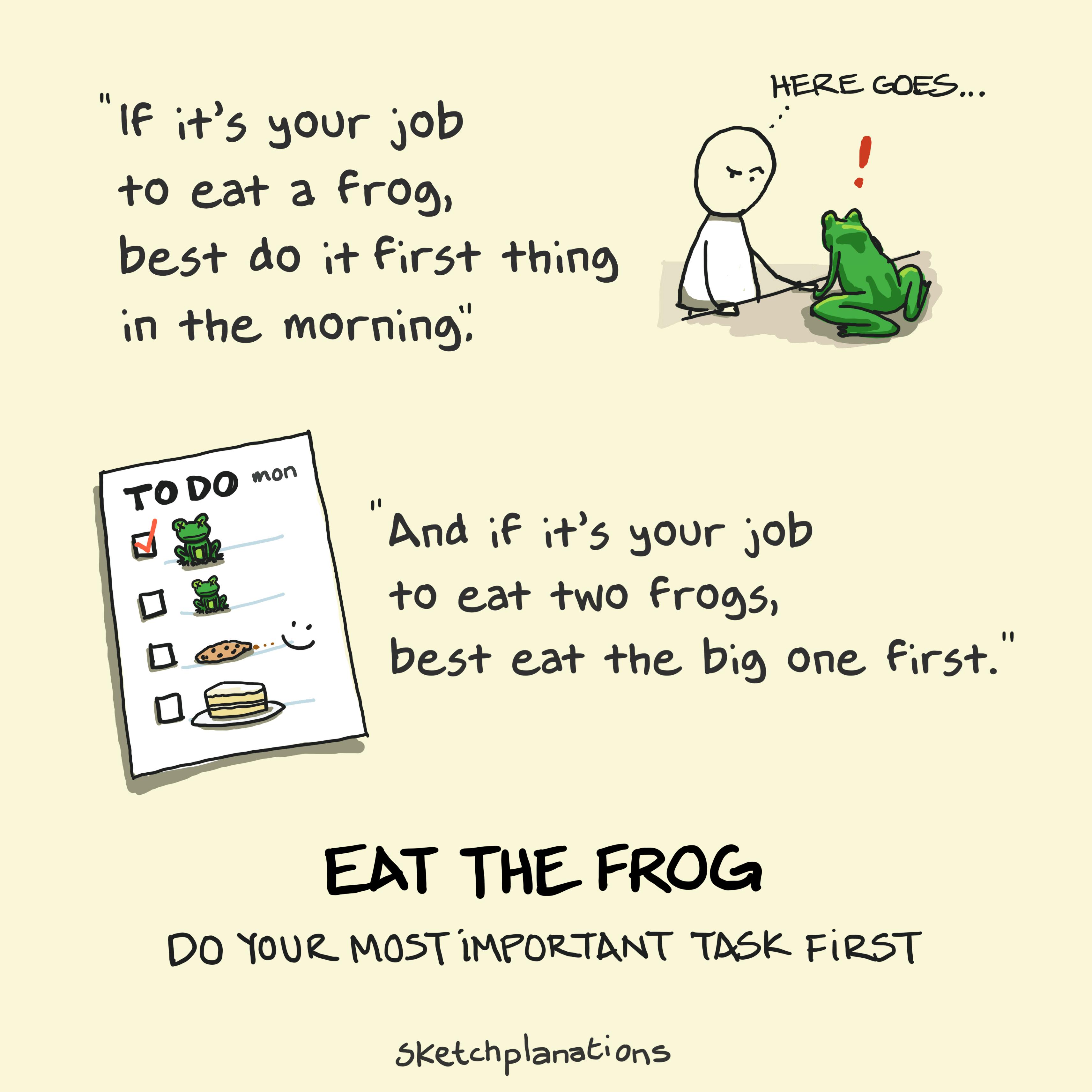

“If it’s your job to eat a frog, it’s best to do it first thing in the morning.”

But what makes this weird metaphor so powerful? The answer lies deep in your psychology. Let’s explore 7 brain-based reasons why this strange little frog might just save your day—and your sanity.

Read More- Sleep and Mental Health

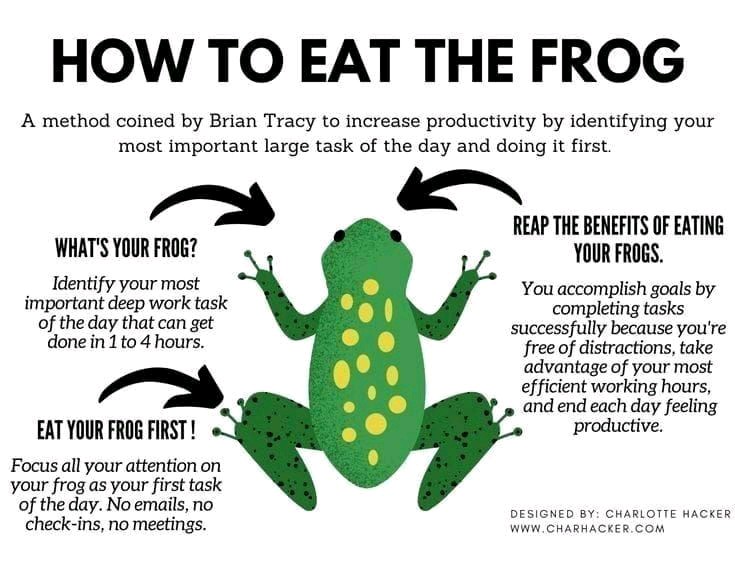

What is “Eat the Frog”?

“Eat the frog” is a popular time-management strategy that means tackling your most difficult or important task first thing in the day—before distractions, procrastination, or fatigue set in. The phrase comes from the idea that if you had to eat a live frog every morning, everything else in your day would feel easier by comparison.

Introduced by Brian Tracy (2001), the technique is rooted in psychological principles like willpower depletion and decision fatigue. By addressing your biggest challenge early, you reduce stress, boost productivity, and create momentum for the rest of your day.

1. Willpower Is Like a Battery—and It Drains Fast

Research shows that willpower is a finite resource. This concept, known as ego depletion (Baumeister et al., 1998), suggests that your ability to make decisions, resist distractions, and take action declines as the day goes on.

By tackling your toughest task early, when your mental battery is full, you maximize your cognitive power and reduce the chances of putting it off forever.

2. Decision Fatigue Is Real—and It’s Brutal

The more decisions you make throughout the day, the worse your decision-making becomes—a concept called decision fatigue (Vohs et al., 2008).

If you don’t eat the frog early, it gets buried under small, energy-draining decisions like choosing outfits or answering Slack messages. By the time you get to it, you’re mentally exhausted—and guess what? The frog wins.

3. The Zeigarnik Effect: Unfinished Tasks Haunt You

Leaving major tasks undone creates mental tension, thanks to the Zeigarnik Effect—a psychological phenomenon where unfinished tasks occupy more mental space than completed ones (Zeigarnik, 1927).

Tackling your frog early clears that looming mental fog and gives you a clean slate for the rest of the day.

4. Momentum Fuels Motivation

Completing a difficult task early triggers what psychologists call success momentum. According to Fishbach and Dhar (2005), early accomplishments can increase motivation and goal persistence.

It’s the “I crushed it” feeling that powers you through smaller tasks. Instead of dragging your feet all day, you ride the wave of early victory.

5. It Reduces Anxiety—and Boosts Mood

Procrastination often leads to guilt and anxiety (Pychyl et al., 2000). Avoiding your frog means carrying stress like an invisible backpack all day.

Eating the frog is like taking off that backpack. It leads to a sense of accomplishment, dopamine release, and reduced cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957).

Mood boost plus productivity? Yes, please.

6. You Train Your Brain to Tackle Discomfort

Let’s be honest: frogs are uncomfortable. That’s the point.

By facing discomfort early, you train your brain to stop avoiding difficult things. This is called psychological resilience—and it’s like a mental muscle that gets stronger with practice (Duckworth et al., 2007).

Plus, it rewires your default response from “delay” to “do.”

7. Morning Focus = Peak Brainpower

Studies on circadian rhythms show that most people have the highest alertness and concentration in the morning (Schmidt et al., 2007). That makes it the perfect time to work on deep-focus tasks like writing, planning, or strategy.

So, eat the frog when your brain is primed for success—not when it’s craving snacks and streaming.

How to Find Your Frog

Here’s a quick cheat sheet to spot your “frog”:

- It’s the task you dread the most

- It has the biggest long-term impact

- It requires deep focus or creativity

- You keep putting it off

Examples: writing that report, making a difficult phone call, starting your thesis, preparing for a presentation, etc.

Be the Frog-Slayer

“Eat the frog” sounds silly, but it’s serious psychology. It’s about creating systems, not just relying on motivation. By understanding how your brain resists effort, you can outsmart procrastination and get stuff done with less stress.

So tomorrow morning, before the emails and distractions hit:

Find your frog. Eat it. Conquer your day.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fishbach, A., & Dhar, R. (2005). Goals as excuses or guides: The liberating effect of perceived goal progress on choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1086/497548

Pychyl, T. A., Morin, R. W., & Salmon, B. R. (2000). Procrastination and the planning fallacy: An examination of the study habits of university students. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 15(5), 135–150.

Schmidt, C., Collette, F., Cajochen, C., & Peigneux, P. (2007). A time to think: Circadian rhythms in human cognition. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24(7), 755–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290701754158

Tracy, B. (2001). Eat that frog!: 21 great ways to stop procrastinating and get more done in less time. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B. J., Twenge, J. M., Nelson, N. M., & Tice, D. M. (2008). Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: A limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 883–898. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.883

Zeigarnik, B. (1927). Über das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen. Psychologische Forschung, 9, 1–85.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, May 9). 7 Brainy and Important Reasons to “Eat the Frog” Every Morning. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/eat-the-frog-every-morning/