Introduction

In the age of rapid technological advancement, artificial intelligence (AI) has become our virtual co-pilot. From composing essays and summarizing research to suggesting what to eat for dinner, AI tools like ChatGPT have embedded themselves into our daily routines. But beneath this convenience lies a subtle cognitive cost. Are we still thinking deeply, or merely pushing buttons?

Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as cognitive offloading—the process of using tools to reduce mental effort. Though offloading isn’t new (think calculators or sticky notes), the scale and sophistication of AI today may be rewiring the very way we process information, solve problems, and learn.

Read More: Digital Amnesia

Understanding Cognitive Offloading

Cognitive offloading refers to the use of external aids to support mental functions (Risko & Gilbert, 2016). For example:

-

Writing down a grocery list instead of memorizing it.

-

Using Google Maps to navigate instead of recalling a route.

-

Letting ChatGPT draft your email instead of composing it yourself.

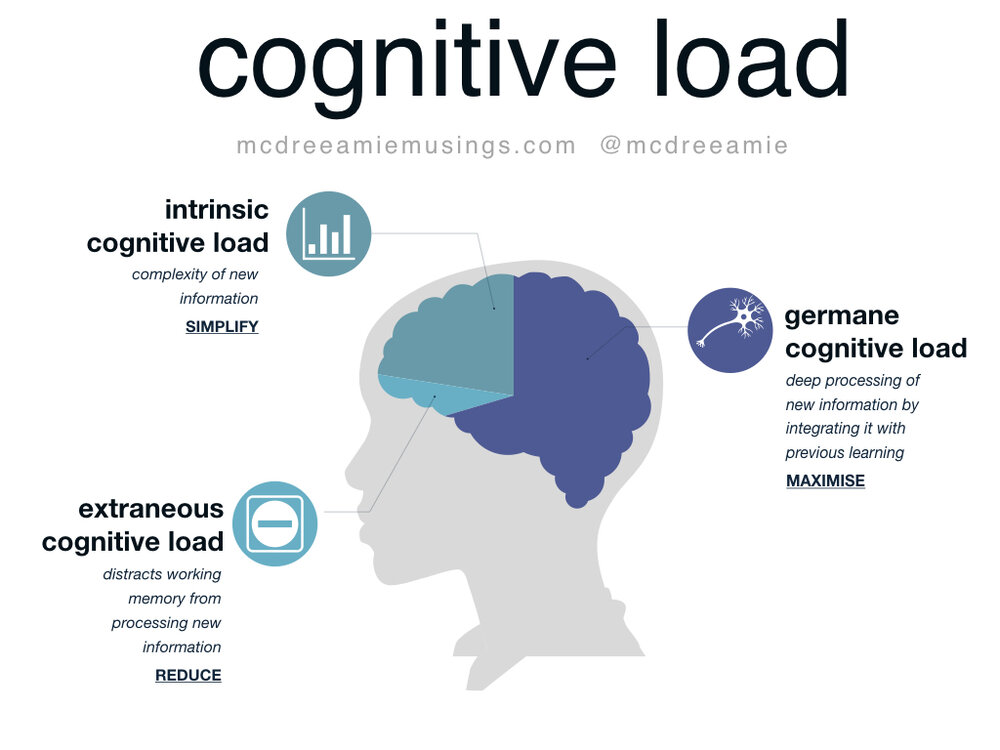

While these strategies increase efficiency, they can reduce internal cognitive load. But over time, habitual reliance on external sources may impair memory formation and problem-solving skills. This echoes research in distributed cognition, which suggests that cognition doesn’t only happen in our heads—it also involves the tools we use (Hollan, Hutchins, & Kirsh, 2000).

The MIT Study

A recent study conducted by the MIT Media Lab (Singh, Chen, & Roberts, 2024) investigated how AI affects our brains during writing tasks. Participants were split into three groups:

-

Manual thinkers who wrote essays without any assistance.

-

Google searchers who could look up facts online.

-

ChatGPT users who could generate and edit content using AI.

The findings were startling:

-

Manual thinkers showed higher EEG-measured brain activity, especially in regions related to attention and memory.

-

ChatGPT users, despite producing polished results, exhibited lower cognitive engagement and poorer memory retention of their own essays.

-

When ChatGPT users were later asked to write without AI, their brain activity remained suppressed, indicating a lingering cognitive disengagement.

This phenomenon was labeled metacognitive laziness—an over-reliance on AI tools that reduces the need for introspection, planning, and self-monitoring.

The Brain Is a Muscle

The brain, like any muscle, strengthens through use. When we struggle to recall a fact or develop an idea from scratch, our brain forms deeper neural connections. This is a process known as effortful retrieval—and it’s essential for long-term learning (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

AI bypasses this struggle. It gives us the answer before we even finish the question. While this seems helpful, it creates a paradox: the easier the tool, the less we think. Over time, reliance on AI can:

-

Reduce our working memory capacity.

-

Erode critical thinking skills.

-

Flatten creative problem-solving abilities.

We’re Cognitive Misers

Psychologists Stanovich and West (2000) described humans as cognitive misers—we instinctively conserve mental energy. We prefer automatic, intuitive shortcuts over effortful, analytical thought. AI tools fit perfectly into this pattern. They do the heavy lifting, and we let them.

This effect is compounded by automation bias, where we tend to trust the output of machines even if it’s flawed (Goddard, Roudsari, & Wyatt, 2012). In practical terms, students may accept AI-written answers without questioning them, and professionals may implement AI-generated strategies without critical evaluation.

Real-World Implications

Educational systems across the world are witnessing dramatic shifts. In Australia, teachers have noted a rise in what’s being termed “digital amnesia”—students submit AI-generated work they can’t explain or defend (O’Neil, 2025). In India, psychologists observed that students who excessively rely on AI show diminished curiosity and creative initiative (Rao, 2025).

A cross-sectional study by Patel and Singh (2025) found that students using AI for more than 10 hours per week scored significantly lower in tasks involving:

-

Independent reasoning

-

Argument construction

-

Critical reading comprehension

Signs You’re Relying Too Much on AI for Thinking

Here’s how to spot if your brain is on autopilot:

-

You can’t explain your own work

If asked to elaborate on something you “wrote” with AI, you’re stumped. -

You default to AI for everything

Even basic tasks like paraphrasing or brainstorming are outsourced. -

You trust AI without verification

You rarely check for factual accuracy or bias in AI-generated content. -

You feel less confident thinking on your own

Blank pages now cause panic without AI guidance. -

You’ve stopped practicing retrieval

You no longer test your own memory—Google or ChatGPT are faster.

Recognizing these patterns is the first step toward regaining cognitive agency.

It’s Not All Doom and Gloom

While it’s easy to paint AI as a villain, context matters. When used thoughtfully, AI can:

-

Spark creative ideas.

-

Offer counterarguments to refine thinking.

-

Help scaffold understanding.

Lee and Yu (2024) propose a concept called “extraheric AI”—AI systems designed not to replace thought but to stimulate it. These tools ask Socratic questions, offer incomplete answers, or generate prompts that require user engagement.

Zhou, Li, and Sun (2023) found that students using AI in a “reflective mode” (i.e., critiquing AI answers, rewriting them, or comparing alternatives) actually improved their critical thinking compared to a control group.

Solutions

To mitigate the cognitive decline linked to passive AI use, psychologists and educators recommend several strategies:

-

Cognitive Forcing Tasks

Require users to question AI responses. For example, “Explain why this might be wrong,” or “Provide two alternative arguments” (Nguyen, Hall, & Garcia, 2023). -

AI Usage Transparency

Schools should mandate students disclose where and how AI was used in assignments (IIT Delhi Committee, 2025). -

Dedicated “Tool-Free” Practice Time

Allocate time for completely offline activities—journaling, brainstorming, debating without AI support. -

AI Literacy Education

Teach not just how to use AI, but when not to. Emphasize tool skepticism, source tracing, and digital ethics.

Try an AI Fast

For one week, avoid AI-generated content. Write, research, and plan manually. Keep a journal of how it feels. Many report initial discomfort followed by a sense of mental clarity, improved focus, and rekindled intellectual ownership.

Think of this as a cognitive reset. Just like fasting resets metabolism, AI fasting may reset metacognition.

Conclusion

AI is powerful. But like all power tools, it must be used with care. When we mindlessly offload our cognitive tasks, we weaken the very abilities that make us human: curiosity, creativity, and critical thought.

Rather than banning AI, we must reframe our relationship with it—not as a replacement for thinking, but as a provocation for deeper thought. In the end, the goal is not to outsmart AI, but to stay smart alongside it.

References

Goddard, K., Roudsari, A., & Wyatt, J. C. (2012). Automation bias: A systematic review of frequency, effect mediators, and mitigators. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 19(1), 121–127.

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E., & Kirsh, D. (2000). Distributed cognition: Toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7(2), 174–196.

IIT Delhi Committee. (2025). AI and academic integrity: Policy guidelines. New Delhi, India.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775.

Lee, H., & Yu, M. (2024). Extraheric AI in education: Prompting, not replacing thought. AI & Society, 39(1), 45–60.

Nguyen, T., Hall, A., & Garcia, S. (2023). Cognitive forcing strategies in the age of automation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 71(2), 201–220.

O’Neil, T. (2025, March 22). Educators warn AI tools may lead to student memory loss. Herald Sun.

Parush, A., Ahuvia, S., & Erev, I. (2007). Degradation in spatial knowledge acquisition when using automatic navigation systems. Cognition, Technology & Work, 9(2), 127–140.

Patel, R., & Singh, A. (2025). Generative AI and adolescent cognition: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Child Psychology, 68(3), 312–325.

Rao, D. (2025, April 11). Creative risk: AI tools and Indian teenagers. Times of India.

Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676–688.

Singh, V., Chen, M., & Roberts, C. (2024). Your brain on ChatGPT: Neural impacts of AI-generated writing. MIT Media Lab Working Paper.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(5), 645–665.

Zhou, F., Li, N., & Sun, J. (2023). AI in education: Dual pathways to student growth. Computers & Education, 189, 104597.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 8). Does AI Change How We Think? 5 Signs That You Are Relying Too Much On It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/does-ai-change-how-we-think/