Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders worldwide, but it does not affect everyone equally—or appear in the same way across genders. While both men and women can experience profound sadness, hopelessness, and loss of motivation, the underlying expression, coping behaviors, and societal responses often differ. Understanding these gender differences is essential for improving diagnosis, treatment, and mental-health awareness.

Read More: High Functioning Depression

1. Biological Foundations of Gender Differences

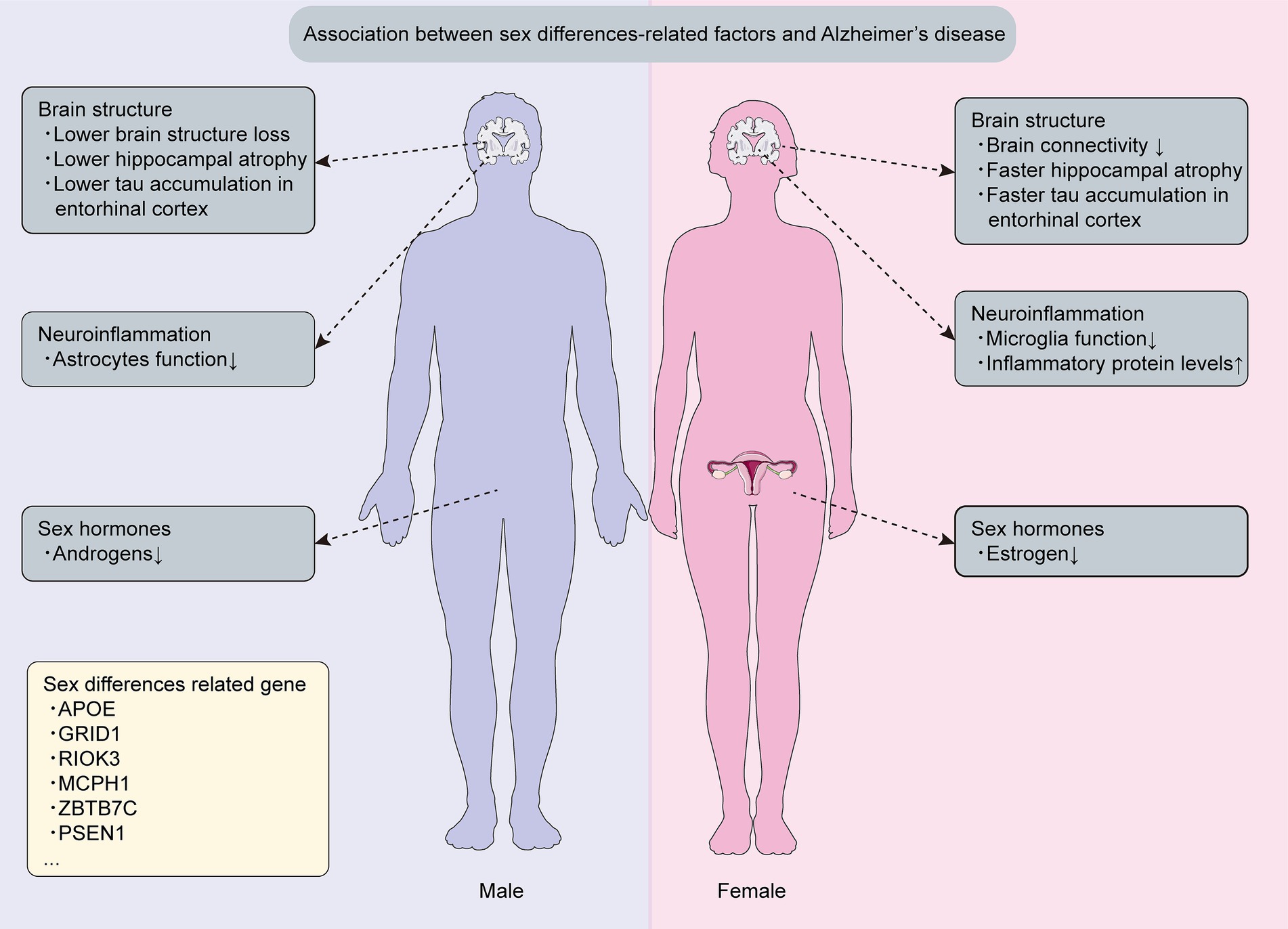

Hormonal and neurobiological differences play a key role in how depression manifests. Women experience fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone across menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and menopause—periods linked to increased vulnerability to mood disturbances (Albert, 2015). Estrogen influences serotonin and dopamine systems, which regulate mood and emotion. Low estrogen levels can reduce serotonin activity, contributing to depressive symptoms (Kuehner, 2017). Men, meanwhile, have higher baseline levels of testosterone, which has been shown to buffer stress and enhance mood regulation. Lower testosterone levels—due to aging, chronic illness, or other factors—can increase depressive symptoms (Zarrouf et al., 2009).

2. Socialization and Gender Norms

Beyond biology, cultural expectations shape how depression is experienced and expressed.

- For Women: Societal norms often encourage emotional expression and interpersonal sensitivity. As a result, women may be more likely to recognize and report feelings of sadness, anxiety, or helplessness. They tend to internalize distress—turning emotions inward—which aligns with the classic symptom profile of depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012).

- For Men: Men are often socialized to suppress emotions, viewing vulnerability as weakness. This can lead to “masked depression”—where sadness is expressed through irritability, anger, or risk-taking behaviors instead of open emotional disclosure (Addis & Mahalik, 2003). Because men’s symptoms may appear as aggression, substance use, or withdrawal rather than sadness, depression in men is frequently underdiagnosed or misinterpreted.

3. Coping Styles and Behavioral Differences

Women are more likely to use emotion-focused coping strategies, such as seeking social support or reflecting on feelings. While this can foster healing, excessive rumination—dwelling on distress—can worsen symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012).

Men tend to favor problem-focused or avoidant coping strategies, such as distraction, denial, or self-medication with alcohol or drugs (Mahalik et al., 2003). These behaviors may temporarily mask emotional pain but can lead to worsening depression or substance-use disorders over time.

4. Suicide and Risk Behaviors

Although women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression, men are more likely to die by suicide (World Health Organization, 2021). This discrepancy is partly due to men’s use of more lethal means and reluctance to seek help. The stigma surrounding male vulnerability prevents many from accessing mental-health care until symptoms become severe.

Addressing these patterns requires not only clinical awareness but also societal change—normalizing emotional openness and challenging harmful gender expectations.

5. Depression Across the Lifespan

Depression looks different across lifespan:

- In Adolescence: Hormonal changes and social pressures can make adolescence a high-risk period, especially for girls. Body image concerns, social media pressures, and relational stress contribute to rising depression rates among young women (Twenge et al., 2019).

- In Adulthood: Women often face “role strain,” balancing work, family, and caregiving responsibilities. Chronic stress and unequal social expectations can heighten vulnerability. Men, conversely, may experience depression triggered by job loss, financial stress, or perceived threats to competence or status.

- In Later Life: Among older adults, depression may manifest as fatigue, irritability, or physical complaints rather than sadness, particularly in men. Loss of identity after retirement or declining physical health can exacerbate symptoms (Blazer, 2003).

Barriers to Treatment

Both biological and social factors influence help-seeking behavior. Women are generally more likely to seek therapy or medication, while men often delay or avoid treatment. Concerns about stigma, masculinity, and control contribute to this gap (Addis & Mahalik, 2003).

Healthcare systems also play a role—diagnostic tools may be biased toward recognizing traditionally “female” symptoms, such as crying or sadness, rather than irritability or anger. Expanding clinical criteria could improve detection among men.

Toward Gender-Sensitive Mental Health Care

Recognizing gendered expressions of depression can improve outcomes. Mental-health professionals are increasingly adopting gender-responsive frameworks, tailoring interventions to biological, psychological, and social realities unique to each group.

For women, treatments may integrate hormonal considerations, social support, and stress management. For men, therapy may focus on emotional literacy, anger regulation, and reframing vulnerability as strength.

Public health campaigns that challenge stigma and encourage help-seeking among men are also crucial to reducing gender disparities in mental-health outcomes.

Conclusion

Depression affects both men and women profoundly but differently. Biological factors, socialization, and cultural expectations all shape how symptoms appear and how individuals respond. Recognizing these differences helps clinicians, families, and individuals respond with greater empathy and precision.

By promoting awareness, reducing stigma, and tailoring treatment approaches, society can ensure that depression—regardless of how it looks—is met with understanding and support rather than silence.

References

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5–14.

Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(4), 219–221.

Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58(3), 249–265.

Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 146–158.

Mahalik, J. R., Burns, S. M., & Syzdek, M. (2003). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 56(11), 2201–2212.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187.

Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators among U.S. adolescents and adults, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 185–199.

World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press.

Zarrouf, F. A., Artz, S., Griffith, J., Sirbu, C., & Kommor, M. (2009). Testosterone and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 15(4), 289–305.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 27). 6 Important Ways Depression Looks Different in Men and Women. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/depression-different-in-men-and-women/