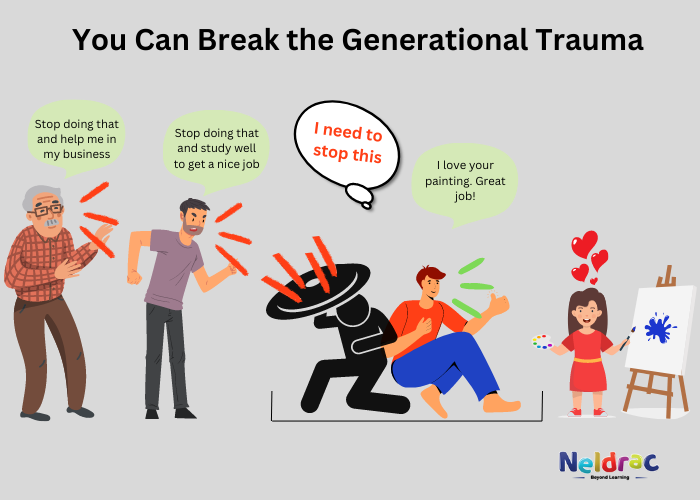

Parenting doesn’t come with an instruction manual—but it often comes with baggage. Many of us grow up carrying patterns from our families: the way our parents spoke to us, disciplined us, showed affection, or failed to. Sometimes those patterns are loving and worth repeating. Other times, they’re heavy cycles of criticism, neglect, or unprocessed trauma that get passed down like unwanted family heirlooms.

Enter the idea of cycle-breaking parenting—the conscious decision to stop repeating harmful patterns and create healthier dynamics for your children. It’s not about being perfect; it’s about being intentional.

Read More: Positive Parenting

What Does It Mean to “Break the Cycle”?

Cycle-breaking parenting means interrupting generational patterns of harm. That might mean:

-

Replacing harsh punishment with discipline rooted in teaching.

-

Breaking the silence around emotions by modeling openness.

-

Refusing to repeat toxic behaviors like gaslighting, favoritism, or neglect.

The goal isn’t to erase the past but to transform it. Psychologists often call this process intergenerational transmission—the way behaviors and trauma echo across generations (Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018). Breaking the cycle means changing that transmission.

The Science of Generational Patterns

Why do cycles repeat in the first place?

-

Modeling: Children imitate what they see. If you grew up with yelling, you may unconsciously yell as a parent (Bandura, 1977).

-

Attachment: Early attachment styles—secure, avoidant, anxious, disorganized—shape how we later bond with others, including our own kids (Bowlby, 1969).

-

Trauma: Trauma doesn’t just affect one person; it echoes biologically and psychologically across generations (Yehuda et al., 2016).

-

Normalization: If you were told “that’s just how families are,” harmful behavior can feel “normal.”

These forces create powerful scripts that cycle-breakers must rewrite.

The Courage to Break the Cycle

Cycle-breaking is brave work. It often means questioning traditions, confronting family pushback, and sitting with uncomfortable truths.

Picture this: you were raised in a “children should be seen and not heard” household. Now, you’re choosing to let your child have a voice. Suddenly, Aunt Margaret is telling you you’re “too soft.” Cycle-breaking means holding your ground and recognizing that being “soft” may actually mean raising emotionally intelligent kids.

Psychologist Brené Brown (2012) notes that vulnerability is the birthplace of courage. Cycle-breaking parents embrace vulnerability—admitting, “I want to do things differently, even if I stumble along the way.”

Tools for Cycle-Breaking Parents

So how do you actually do it? Here are some key tools:

1. Self-Awareness

You can’t break what you don’t see. Journaling, therapy, or simply reflecting on questions like, “What did I need as a child that I didn’t get?” can help illuminate patterns.

2. Emotional Regulation

Cycle-breaking means learning to pause before reacting. Deep breathing, mindfulness, or even the age-old trick of “count to ten before speaking” can shift moments of conflict.

3. Positive Discipline

Instead of punishment, cycle-breakers often use discipline strategies that teach and guide. Psychologists like Baumrind (1966) found that authoritative parenting—a balance of warmth and structure—leads to healthier outcomes than authoritarian or permissive styles.

4. Communication

Talking about feelings is radical in families where emotions were once taboo. Phrases like “I’m feeling overwhelmed” or “I hear you’re angry” model emotional literacy.

5. Support Systems

Therapy, parenting groups, or even online communities of “cycle breakers” provide validation and strategies. Breaking cycles doesn’t mean doing it alone.

Humor Helps

Let’s be honest: cycle-breaking isn’t glamorous. Sometimes it looks like you Googling “how not to yell at my kid” while hiding in the bathroom. Or saying, “I’m sorry, Mommy was hangry,” for the fourth time in a week.

Humor helps lighten the load. Laughter releases tension and reminds us that breaking cycles is about progress, not perfection. As clinical psychologist Donald Winnicott (1965) argued, the goal isn’t a “perfect parent” but a “good enough” one—present, responsive, and human.

The Ripple Effect

When you break a cycle, the effects ripple far beyond your own children. Studies on resilience show that when one generation interrupts trauma, it can positively affect mental health and outcomes in subsequent generations (Masten, 2014).

Cycle-breaking parents are like gardeners, planting seeds of healthier patterns—seeds that can blossom into stronger family trees for decades to come.

Breaking Myths About Cycle-Breaking

-

Myth 1: If I slip up, I’ve failed.

Truth: Breaking cycles is about consistency, not perfection. Repairing after mistakes models growth. -

Myth 2: My family will understand right away.

Truth: Expect resistance. Change can feel threatening to those invested in “the old way.” -

Myth 3: It’s too late.

Truth: Cycle-breaking can happen at any age—even with grown kids. Repair, apology, and change are always possible.

Why Cycle-Breaking Matters

Breaking cycles is more than just parenting; it’s activism at the family level. It challenges old power structures, heals wounds, and sets new norms. It teaches children that love doesn’t have to hurt, that discipline doesn’t have to humiliate, and that mistakes can be repaired.

It’s not just about raising happier kids. It’s about raising kids who don’t have to spend their adult lives unlearning pain.

Conclusion

Cycle-breaking parenting is both messy and magical. It asks us to face our past while rewriting our future. It’s laughing at our stumbles, crying when it’s hard, apologizing often, and reminding ourselves: I’m not trying to be perfect, I’m trying to be better.

In doing so, cycle-breaking parents become quiet revolutionaries—reshaping the inheritance they pass on. Not just genetics, not just heirlooms, but legacies of empathy, resilience, and love.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Gotham Books.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. International Universities Press.

Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Lehrner, A., Desarnaud, F., Bader, H. N., Makotkine, I., … Meaney, M. J. (2016). Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(8), 856–864.

Yehuda, R., & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: Putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243–257.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 13). Cycle-Breaking Parenting and 4 Important Science of Generational Patterns. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/cycle-breaking-parenting/