Imagine you just got promoted. In the U.S., you might grin ear-to-ear, post about it online, and pop champagne with friends. In Japan, however, you might keep your excitement subdued, modestly thanking your team while keeping your smile small. Same emotion, different performance. Welcome to the wonderfully weird world of cultural differences in emotional expression.

Read More: Emotions SOS

Do Smiles Speak the Same Language Everywhere?

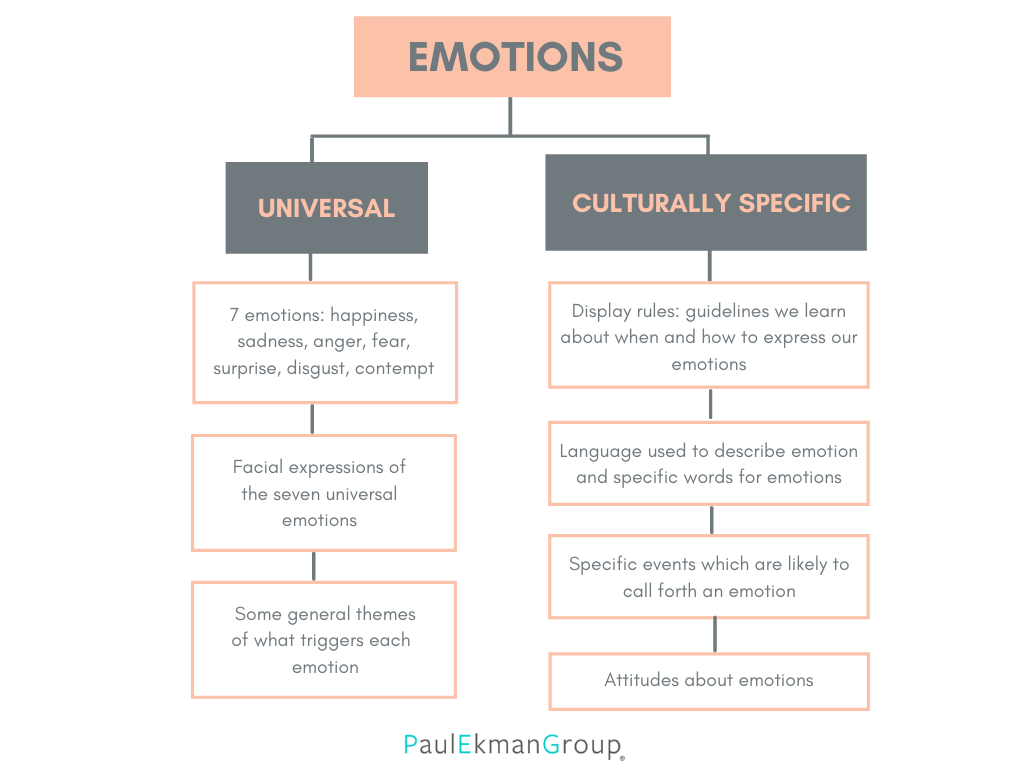

You might think a smile is universal—everyone knows it means “I’m happy.” But not so fast. Psychologists have discovered that while the capacity for emotion is universal, the rules for expressing emotions—called display rules—vary widely across cultures (Ekman & Friesen, 1969).

For example:

- In the U.S., smiling is practically a national pastime. Americans smile at strangers on the street.

- In Russia, smiling at strangers can be seen as insincere or even suspicious (Safdar et al., 2009).

- In Japan, people often smile to mask negative feelings, such as embarrassment or discomfort, rather than happiness (Matsumoto & Kudoh, 1993).

So, while the biological machinery for smiling is built-in, the meaning of a smile depends on where you are.

Display Rules

The idea of display rules comes from Paul Ekman, one of the first psychologists to study facial expressions across cultures. Display rules are the unspoken guidelines about when, where, and how much emotion you should show (Ekman & Friesen, 1969).

Think of them like a cultural filter:

-

In some cultures (like the U.S. or Brazil), emotional expression is encouraged—“show how you feel!”

-

In others (like Japan or Korea), emotional restraint is prized—“don’t make waves.”

This is why Westerners sometimes perceive East Asians as “less emotional,” while East Asians may view Westerners as “too dramatic.” Neither is true—both are simply following their culture’s playbook.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

A huge factor shaping emotional expression is whether a culture leans individualistic (focused on the self) or collectivistic (focused on the group).

-

Individualistic cultures (like the U.S., Canada, or much of Western Europe) encourage open expression of emotions, since personal authenticity and uniqueness are valued (Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

-

Collectivistic cultures (like Japan, China, or Korea) encourage restraint, since harmony and group cohesion are more important than individual feelings.

For instance, an American might proudly express anger if treated unfairly (“That’s not right!”), while a Japanese person in the same situation might suppress anger to avoid disrupting group harmony.

Are Tears Created Equal?

Even crying is culturally coded. Research shows that people in Western countries report crying more frequently and intensely than those in collectivistic cultures (Fischer et al., 2013).

It’s not that people in Japan or China feel sadness less often—it’s that cultural norms discourage emotional outbursts in public. In contrast, many Western cultures encourage emotional “release,” framing it as healthy and authentic.

When Emotions Get Lost in Translation

Here’s where things get funny (and sometimes awkward). Misreading cultural expressions of emotion can lead to misunderstandings.

Picture this: An American businessman gives a big, enthusiastic smile during a meeting. His Japanese counterpart politely returns a small, tight smile. The American interprets this as lack of interest, while the Japanese colleague may simply be following display rules for modesty.

Psychologists call this cross-cultural misattribution—assuming that other people’s emotional displays mean the same thing they would in your culture (Matsumoto, 1990). It’s the social equivalent of a bad Google Translate.

The Role of Globalization

Now, here’s where things get interesting: globalization is blurring some of these cultural lines. Thanks to Hollywood, TikTok, and K-pop, people around the world are increasingly exposed to different emotional “dialects.”

For instance, young people in Japan may be more expressive than their grandparents, influenced by Western media. Similarly, Westerners are learning that stoicism or subtlety in expression doesn’t necessarily mean someone is unfeeling—it might mean they’re respectful.

What the Brain Says

Interestingly, brain studies show that people are better at recognizing emotions expressed within their own culture than from others—a phenomenon called the in-group advantage (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

In other words, you might be great at spotting your best friend’s sarcastic eye-roll, but less skilled at interpreting the subtle expressions of someone from a different cultural background. It’s not a lack of empathy—it’s a lack of shared cultural coding.

The Takeaway

Emotions are universal, but their expressions are cultural performances. A smile in Tokyo might not mean the same thing as a smile in Toronto. A tear in New York might roll for different social reasons than one in Seoul.

The next time you’re traveling—or even just chatting online with someone from a different background—remember that what looks like stoicism, exaggeration, or even insincerity might just be a different emotional accent. After all, feelings are human, but how we show them is cultural.

References

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica, 1(1), 49–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1969.1.1.49

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 203–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203

Fischer, A. H., Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., van Vianen, A. E., & Manstead, A. S. (2013). Gender and culture differences in emotion. Emotion, 4(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.87

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Matsumoto, D. (1990). Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motivation and Emotion, 14(3), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00995569

Matsumoto, D., & Kudoh, T. (1993). American-Japanese cultural differences in judgments of expression intensity and subjective experience. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 24(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022193244003

Safdar, S., Friedlmeier, W., Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., Kwantes, C. T., Kakai, H., & Shigemasu, E. (2009). Variations of emotional display rules within and across cultures: A comparison between Canada, USA, and Japan. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 41(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014387

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,027 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 25). Cultural Differences in Emotions as Seen Across 2 Main Cultures. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/cultural-differences-in-emotions/