Introduction

You’re working on an important project, lost in thought — and then ding! A message pops up. You glance at it, decide it’s nothing urgent, and return to work. But something’s changed. You’ve lost your rhythm, your flow, and your train of thought.

This everyday experience illustrates a powerful, invisible phenomenon shaping the modern mind: the cognitive cost of constant notifications. From smartphones to smartwatches, our lives are punctuated by digital interruptions that fragment attention, alter cognitive load, and subtly rewire how we think, remember, and focus.

Read More: Social Media and Identity

The Science of Attention and Interruption

Cognitive psychology has long established that attention is a limited resource. Daniel Kahneman’s (1973) capacity model of attention proposed that humans have a finite amount of mental energy available for cognitive tasks. Each new demand — such as a notification — consumes a portion of this capacity.

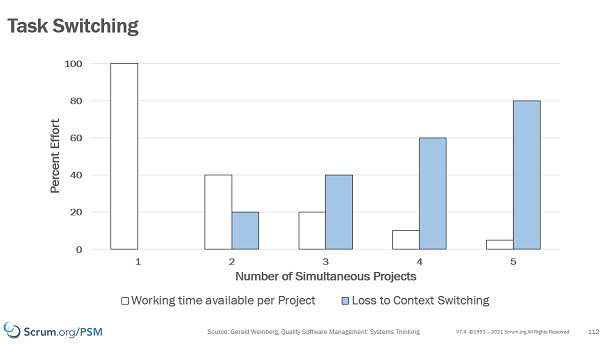

When a notification interrupts a task, the brain must engage in task switching, shifting from one mental context to another. While this may feel instantaneous, it’s not. Rubinstein, Meyer, and Evans (2001) found that task-switching introduces measurable “switching costs” — extra time and mental effort required to reorient after an interruption. Even brief diversions can degrade performance and increase the likelihood of errors.

In everyday terms, every buzz or ping demands a micro-shift in focus, a cognitive toll that accumulates over time.

Micro-Interruptions and Cognitive Load

Not all interruptions are equal. A brief sound alert may seem harmless compared to an incoming call, yet research shows that even unattended notifications can impair performance. Stothart, Mitchum, and Yehnert (2015) demonstrated that hearing a phone notification — without even checking it — was enough to reduce participants’ accuracy and speed on attention-based tasks.

This phenomenon is linked to cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988), which posits that our working memory can only hold a limited amount of information at once. Notifications, even if ignored, create extraneous cognitive load — mental noise that competes with the task at hand.

In a world where the average person receives between 50 and 80 notifications per day (Deloitte, 2023), these micro-interruptions form a persistent background hum that subtly depletes cognitive resources.

The Cost to Deep Work

Cal Newport (2016) popularized the term deep work to describe cognitively demanding, distraction-free tasks that produce meaningful results. Deep work requires sustained attention and immersion, yet modern work environments make such focus increasingly rare.

A study by Mark, Gudith, and Klocke (2008) found that knowledge workers are interrupted roughly every 11 minutes, and it can take up to 25 minutes to return to the original level of focus. Notifications contribute significantly to this disruption cycle, reducing both productivity and creativity.

When attention is fragmented, people engage in shallow work — quick responses, multitasking, and reactive behavior — which may feel busy but yields lower cognitive value. The constant availability demanded by notifications promotes a culture of immediacy at the expense of depth.

Neurological Impacts

Notifications also exploit our brain’s reward systems. Every ping signals the possibility of something new — a message, a like, an update — which triggers the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with anticipation and reward (Kringelbach & Berridge, 2016).

This intermittent reinforcement schedule mirrors the psychology of slot machines: unpredictable rewards keep users checking compulsively. The anticipation of reward becomes more powerful than the reward itself. Over time, this cycle conditions the brain to seek stimulation rather than focus, eroding sustained attention spans.

A 2017 study by Kushlev, Proulx, and Dunn found that participants who received notifications frequently throughout the day reported higher stress and lower productivity than those who had them disabled. The brain learns to crave microbursts of stimulation, even when they are cognitively draining.

Emotional and Psychological Consequences

Beyond performance, constant interruptions carry emotional costs. The frequent shifts between tasks can produce a subtle sense of anxiety — the feeling of being perpetually “on call.” Psychologists call this attention residue, a term coined by Leroy (2009) to describe the lingering thoughts and emotions from one task that interfere with the next.

When notifications interrupt deep concentration, the mind doesn’t instantly detach from the previous task. Instead, a portion of attention remains stuck, reducing overall cognitive performance. Over time, this fragmented state can contribute to mental fatigue, irritability, and reduced emotional resilience.

Moreover, the social dimension of notifications — messages, mentions, and tags — adds a layer of emotional salience. Each ping may trigger thoughts like “Who needs me?” or “Am I missing something?”, further anchoring attention to external stimuli.

The Paradox of Connectivity

Ironically, the very tools designed to keep us connected may be isolating us from our own cognitive presence. In seeking constant updates, we lose the ability to be in a single moment without distraction.

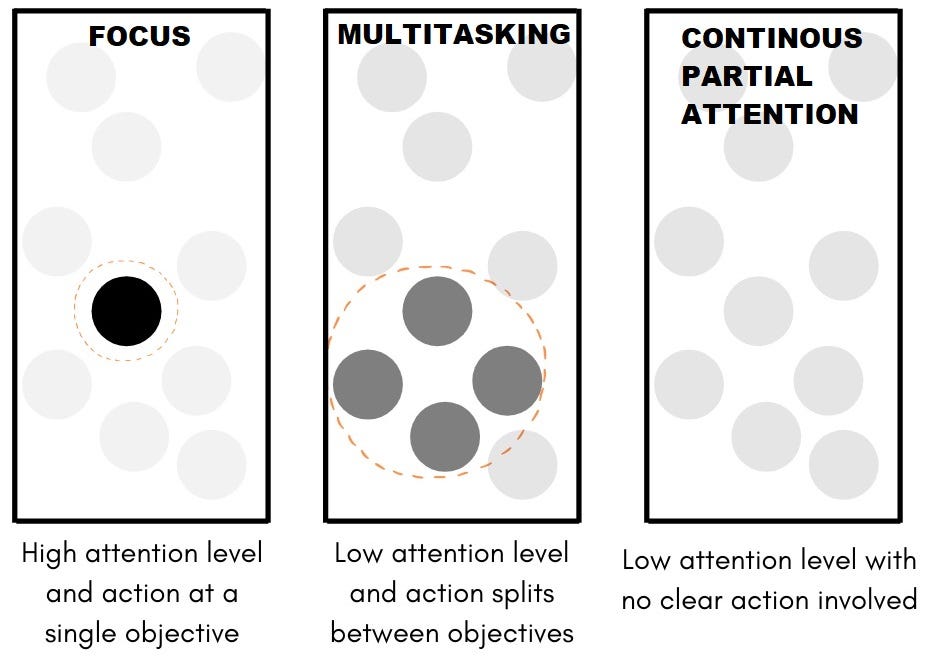

This phenomenon has been called “continuous partial attention” (Stone, 2007) — a state in which individuals constantly scan multiple streams of information without fully engaging with any. Unlike multitasking, which involves juggling tasks, continuous partial attention is about never turning off alertness. It keeps the nervous system in a mild state of fight-or-flight, subtly taxing mental health.

Notifications exploit this vigilance. A silent phone can feel like a relief; a buzzing one feels like a demand. The line between work and rest dissolves as alerts follow us across time zones and personal boundaries.

Strategies for Reclaiming Attention

While turning off notifications entirely may seem ideal, it’s often impractical in professional and social contexts. Instead, psychologists recommend strategic attention management:

-

Batch notifications — Schedule set times to check messages rather than reacting to each one immediately (Kushlev & Dunn, 2015).

-

Use “focus modes” or “do not disturb” — Reduce unnecessary alerts during high-focus periods.

-

Mindful checking — Before responding to a ping, pause to ask: “Is this urgent, or just habit?”

-

Environmental design — Keep the phone physically out of sight while working; even its presence can reduce cognitive performance (Ward et al., 2017).

-

Digital hygiene — Audit which apps truly deserve notification privileges. Many do not.

Over time, these small behavioral changes can retrain attention systems, restoring cognitive continuity and reducing stress.

The Future of Notifications

Technology designers are increasingly aware of these cognitive costs. The field of calm technology (Weiser & Brown, 1996) advocates for systems that inform without demanding constant attention — for example, adaptive notifications that appear only when contextually relevant.

Artificial intelligence may eventually tailor notification delivery based on cognitive state, time of day, or emotional load. However, without ethical oversight, such systems risk deepening dependence rather than restoring autonomy.

Ultimately, the challenge lies not just in technology, but in culture. As long as speed and responsiveness remain social currency, the expectation to always be available will persist — regardless of the toll on cognition.

Conclusion

Every ping, buzz, and banner carries more than a sound; it carries a cost. The modern attention economy thrives on fragmentation, pulling focus from one moment to the next. Yet beneath the convenience of constant connection lies an erosion of cognitive depth — a subtle rewiring of how we think, work, and even feel.

To reclaim attention is to reclaim agency. By managing notifications mindfully, we can reestablish boundaries around thought, restore our capacity for deep focus, and protect the most valuable resource of all: the ability to be fully present.

References

Deloitte. (2023). Global Mobile Consumer Survey.

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and Effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kringelbach, M. L., & Berridge, K. C. (2016). The neuroscience of pleasure and happiness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(1), 1–15.

Kushlev, K., Proulx, J., & Dunn, E. W. (2017). “Silence Your Phones”: Smartphone Notifications Increase Inattention and Hyperactivity Symptoms. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 175–182.

Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residue when switching between work tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 168–181.

Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 107–110.

Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Rubinstein, J. S., Meyer, D. E., & Evans, J. E. (2001). Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(4), 763–797.

Stothart, C., Mitchum, A., & Yehnert, C. (2015). The attentional cost of receiving a cell phone notification. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41(4), 893–897.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. W. (2017). Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140–154.

Weiser, M., & Brown, J. S. (1996). Designing calm technology. PowerGrid Journal, 1(1), 75–85.

Stone, L. (2007). Continuous partial attention. Harvard Business Review, 85(6), 29–32.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 12). The Cognitive Cost of Notifications and 5 Important Strategies to Reclaim Attention. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/cognitive-cost-of-notifications/