Introduction

Why did you hold the elevator for that stranger? Or donate to a disaster relief fund even when you’re strapped for cash? Altruism—doing good without expecting anything in return—has puzzled scientists for decades. On the surface, it seems wonderfully human. But beneath the warm fuzzies, are our kind acts driven by emotion, or is there a deeper, colder logic ticking away in our brains?

Welcome to the curious case of cognitive altruism, where emotion meets evolution, and your brain might just be a strategic do-gooder in disguise.

Read More- Emotions SOS

Warm Hearts or Cool Calculations?

Altruism seems irrational at first glance. Evolution should favor self-preservation, right? Yet here we are, jumping into rivers to save strangers and sharing food in famine. Classic evolutionary theorists like Charles Darwin even found this troubling. In The Descent of Man (1871), he noted how altruistic behavior toward non-kin was hard to explain by survival of the fittest alone.

So, why do we help?

Traditionally, psychologists have emphasized emotional impulses—empathy, guilt, compassion. Think of Daniel Batson’s Empathy-Altruism Hypothesis (1991), which argues that empathic concern leads to truly selfless behavior, even at a personal cost.

But enter the cognitive camp, where altruism is viewed through a colder lens. What if your brain is doing the math—costs, benefits, social consequences—before you even finish saying, “I’m just trying to help”?

The Rational Brain’s Secret Altruism Agenda

Recent research supports the idea that altruism isn’t purely emotional. In fact, rational, prefrontal parts of the brain light up when we decide to help others—especially in situations where there’s no emotional trigger.

One fascinating study by Moll et al. (2006) used fMRI to examine brain activity during charitable donations. They found that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)—a region linked to decision-making and valuation—was more active when participants donated money voluntarily. Interestingly, this activation mirrored patterns seen during financial reward processing.

Translation? Helping felt good, but it was also being “scored” cognitively—your brain was doing a cost-benefit analysis in real time.

The Dictator Game and Strategic Kindness

Want proof of cognitive altruism? Look no further than the Dictator Game, a staple in behavioral economics.

In this game, one person (the “dictator”) gets a sum of money and decides how much to give to another player, who has no say. You’d expect pure selfishness—but most people give a portion, even if just a little. Why?

One theory: reputation management. A study by Haley and Fessler (2005) found that when participants believed they were being watched (even by stylized eye images), their generosity increased. That’s not just empathy—it’s strategic thinking. The mind calculates social rewards, potential reciprocity, or the future need to be seen as “good.”

Even toddlers do this! In a study by Leimgruber et al. (2012), children aged 5 were more generous when they thought someone was watching. Altruism may bloom early, but it’s fertilized with strategy.

Emotion vs. Cognition

But let’s not throw empathy out with the bathwater. Emotional and rational pathways often work together—not against each other.

The insula, a brain region tied to empathy and emotional pain, is active when we witness others suffering (Singer et al., 2004). It pulls at our heartstrings. But the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) steps in to regulate that impulse, weighing the long-term benefits and consequences.

This dynamic is beautifully captured in dual-process theories of moral decision-making (Greene et al., 2001), where System 1 (fast, emotional) and System 2 (slow, rational) both influence our choices.

Imagine you see someone drop their groceries. Your heart instantly tugs (System 1), but your brain considers whether you’re late for work (System 2). You help—but your decision wasn’t just kind; it was calculated kindness.

Reciprocal and Inclusive Altruism

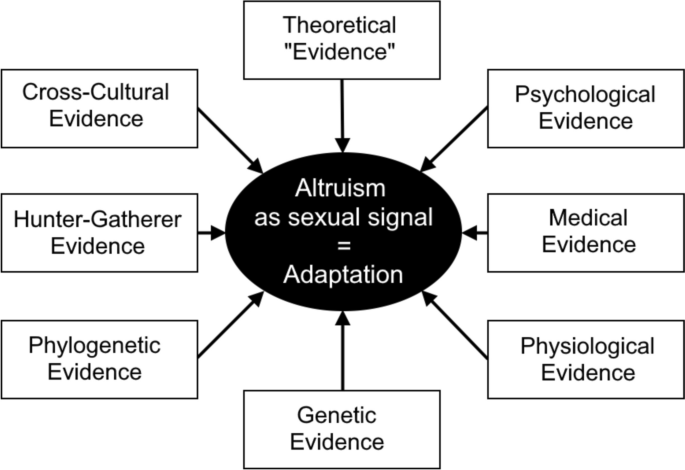

From an evolutionary lens, altruism as a strategy makes perfect sense. Concepts like reciprocal altruism (Trivers, 1971) and inclusive fitness (Hamilton, 1964) explain how helping behaviors can increase the survival of your genes—even if you don’t benefit immediately.

Your ancestors who helped others in their tribe may have built alliances, ensured mutual survival, or enhanced their mating prospects (yes, kindness is sexy). These behaviors were selected for, not despite their cost, but because of their strategic benefits over time.

In other words, your brain might be hardwired to care—but only because it helped your ancestors get ahead.

So, Are We Truly Selfless?

That’s the million-dollar question. If every act of kindness is secretly rewarded—socially, emotionally, or evolutionarily—can it still be called altruism?

Philosophers have wrestled with this for centuries. But perhaps the better question is: Does it matter?

Whether we help because it feels good, looks good, or is good, the outcome is the same—a better world, one kind act at a time. And if evolution made us that way, maybe that’s not cold logic—it’s beautifully efficient.

References

Batson, C. D. (1991). The Altruism Question: Toward a Social-Psychological Answer. Psychology Press.

Greene, J. D., et al. (2001). “An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment.” Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). “The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour.” Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 1–52.

Haley, K. J., & Fessler, D. M. T. (2005). “Nobody’s Watching? Subtle Cues Affect Generosity in an Anonymous Economic Game.” Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(3), 245–256.

Leimgruber, K. L., et al. (2012). “Give What You Get: Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus apella) and 5-Year-Old Children Pay Forward Positive and Negative Outcomes to Conspecifics.” PLOS ONE, 7(10): e47744.

Moll, J., et al. (2006). “Human Fronto–Mesolimbic Networks Guide Decisions About Charitable Donation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(42), 15623–15628.

Singer, T., et al. (2004). “Empathy for Pain Involves the Affective but Not Sensory Components of Pain.” Science, 303(5661), 1157–1162.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.” Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35–57.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,045 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 15). Cognitive Altruism: Are We Wired to Help for Rational or Emotional Reasons?. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/cognitive-altruism/