Introduction

Imagine waking at dawn, alert and motivated—or struggling to step out of bed until midday despite urgent deadlines. That’s chronopsychology at work: how your internal clock shapes not just sleep, but your personality, decision-making, health, and social life. Whether you’re a “lark” or an “owl,” your chronotype—your biological preference for earlier or later activity—guides your behavior in profound ways (Venkat et al., 2020; Adan et al., 2012).

Read More- Sleep and Mental Health

What Are Chronotypes?

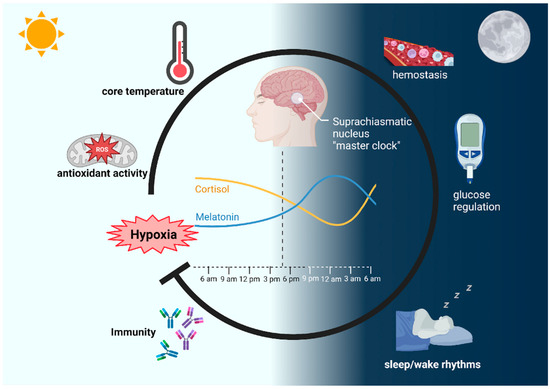

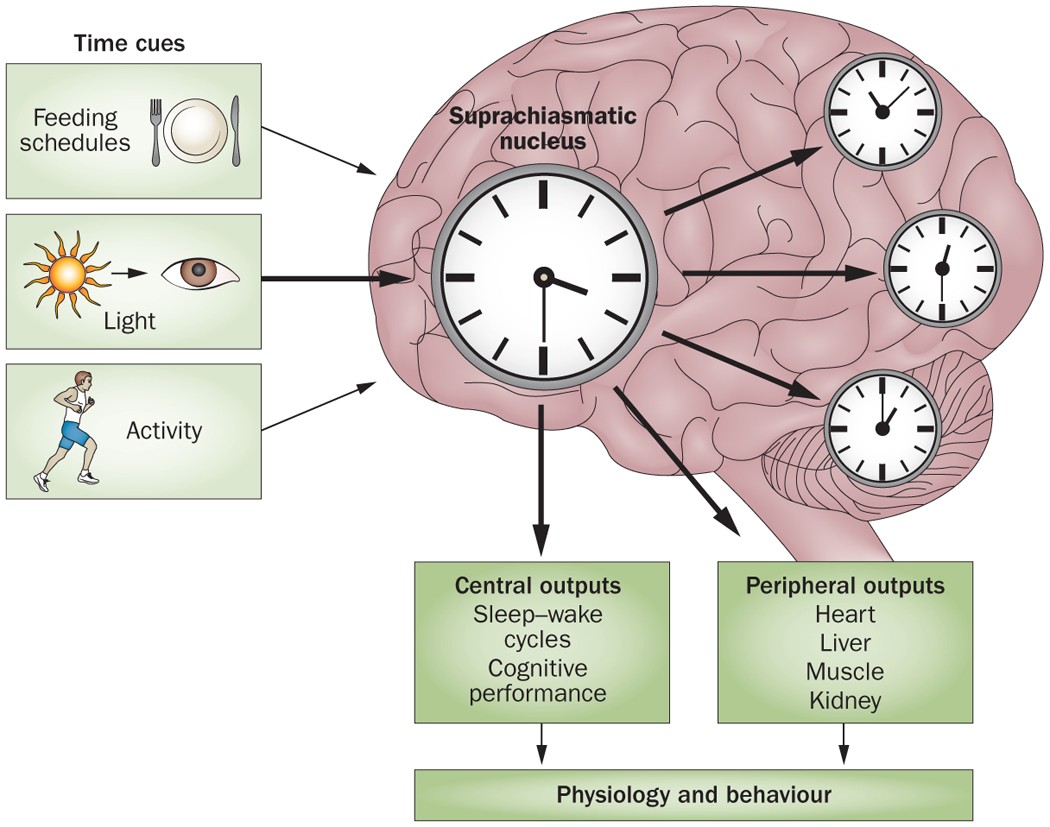

Chronotypes reflect when your circadian rhythm promotes alertness. On a spectrum from extreme morning-lovers (“larks”) to late-night owls, most people land somewhere in between (Roenneberg & Merrow, 2007). Biological underpinnings include genes like PER3 and CLOCK, which influence how early or late your melatonin cycles begin (Skene, 2025; Wikipedia, 2025). These rhythms modulate sleep tendency, hormone secretion, energy levels, and cognitive performance (Venkat et al., 2020).

Rodent and fish studies show chronotype tied to coping style and hormone rhythms: proactive “early” individuals display stronger cortisol/melatonin cycles, while reactive types have weaker ones (Kirste et al., 2018). Similar patterns hold in humans, although culturally mediated (de Vet et al., 2018).

Personality & Chronotype

Morning Types tend to be…

- Conscientious and disciplined

- Introverted or cooperative

- Emotionally stable and resistant to stress (Adan et al., 2012; Lipnevich et al., 2017; Soehner et al., 2007)

- Better at analytic/rational thinking (Diaz-Martales & Escribano, 2013)

Evening Types often show…

- Extraversion, openness, and impulsivity

- Higher novelty-seeking, risk-proneness, and rumination

- Greater emotional variability and neuroticism (Adan et al., 2012; Lipnevich et al., 2017; Antypa et al., 2017)

- May score higher on “psychoticism”-like traits (Adan et al., 2012)

Morning types often excel academically; evening types exhibit strong raw cognitive ability but may struggle in early-day environments (Venkat et al., 2020).

Chronotype & Risk

Research clearly shows evening types tend to take more risks, across domains—financial, ethical, recreational (Song et al., 2023; Venkat et al., 2020). This link is mediated by:

- Lower self-control

- Higher impulsivity

- Reduced emotional stability

A chain-mediation model revealed eveningness predicts lower self-control → lower emotional stability → higher risk-taking behaviors (Song et al., 2023).

Morning types display opposite patterns: more self-control, lower impulsivity, and less risk-taking (Song et al., 2023).

When Your Body Clock Clashes with Life

Evening chronotypes are more susceptible to:

- Depression, anxiety, mood disorders

- Possibly eating disorders and addictive behaviors

- Rumination and negative self-referential thinking

These associations hold even after adjusting for sleep quality, suggesting intrinsic chronotype effects (Antypa et al., 2017; Adan et al., 2012; Current Sleep Reports, 2018).

Evening types are more likely to:

- Eat late, less healthily

- Exercise less

- Experience poorer overall health perceptions (Current Sleep Reports, 2018)

However, links to obesity remain inconsistent; some studies show lower BMI in evening types (Current Sleep Reports, 2018).

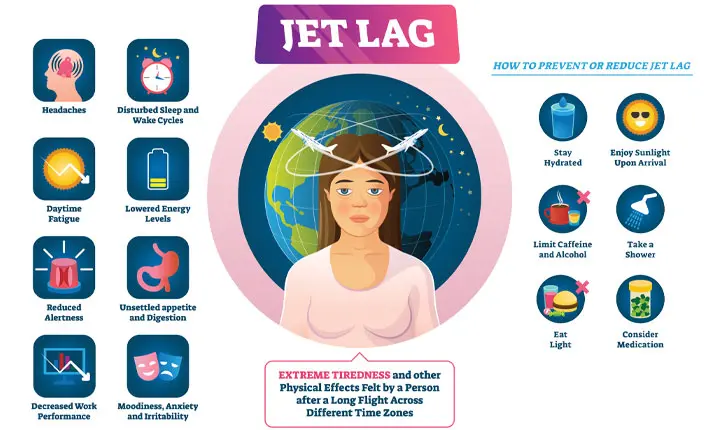

Social Jet Lag

If your natural rhythm clashes with work or school hours, you suffer “social jet lag.” This misalignment is linked to mood swings, lowered academic performance, and stress (Gapate et al., 2025; Bianchi et al., 2023).

Even youth exposed to adverse social environments show heightened mental health risks when eveningness intersects with poor support and high-risk behavior patterns (Bianchi et al., 2023). Chronotype isn’t just personal rhythm—it affects how well you thrive in your environment.

The Synchrony Effect

We perform better at tasks that align with our peak arousal times (Venkat et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2015). This “synchrony effect” means:

- Morning types excel in early-day tests

- Evening types perform better in the evening

Mismatch leads to underperformance—even if raw potential remains unchanged (Venkat et al., 2020; Nanditha et al., 2020). Morning tests disadvantage night owls, leading to unfair evaluations.

Social & Cultural Ripples of Chronotype

Evening types typically have:

-

Larger but shallower social networks

-

Higher centrality in social graphs

-

Strong homophily—they often socialize with fellow owls (Aledavood et al., 2017)

These network patterns reflect social rhythms that influence opportunities and interactions.

Practical Tips to Align Your Clock

Some ways to do this include-

- Identify your chronotype – Try the MEQ or Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (Roenneberg et al., 2007)

- Use light intentionally – Bright AM light supports morningness; minimized blue light at night helps evening types wind down

- Time critical tasks right – Morning peak for larks; evening seminars or creative work for owls

- Shift schedules gradually – Adjust in phases of 15–30 minutes to reset your clock

- Prioritize sleep health – Late nights + early mornings = chronic fatigue

- On weekends, taper wake times – Avoid large discrepancies to reduce social jet lag

Conclusion

Your internal clock is more than your sleep schedule—it’s a lens through which personality, behavior, health, and social life are filtered. Recognizing your rhythm isn’t about limiting yourself; it’s about synchronizing your life for peak performance, well-being, and harmony.

It’s simple: align key tasks with your peak times, optimize light exposure, and adjust sleep habits gradually. Whether you’re a sunrise sprinter or a midnight marathoner, chronopsychology offers insights to live in sync with your true self.

References

Adan, A., Archer, S. N., Hidalgo, M. P., Di Milia, L., Natale, V., & Randler, C. (2012). Circadian preference and personality. Chronobiology International, 29(10), 1179–1201.

Aledavood, T., Lehmann, S., & Saramäki, J. (2017). Social network differences of chronotypes identified from mobile phone data. arXiv.

Antypa, N., Vogelzangs, N., Meesters, Y., Schoevers, R. A., & Penninx, B. W. (2017). Chronotype associations with depression and adaptation to morningness-eveningness schedules. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 1–7.

Bianchi, M., Zhong, Z., Xuan, Z., et al. (2023). Relationship between chronotype and mental behavioral health among adolescents. BMC Psychiatry.

de Vet, A. J., et al. (2018). Biological clock function and coping style. BMC Biology.

Diaz-Morales, J. F., & Escribano, C. (2013). Chronotype and cognitive style in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 411–419.

Gapate, S., Smarr, B., et al. (2025). Evidence for modality-dependent chronotype assessments. arXiv.

Kirste, I., Nicola, Z., et al. (2018). Clock genes and behavioral phenotypes in zebrafish. BMC Biology.

Lipnevich, A. et al. (2017). Meta-analysis of chronotype and personality. Journal of Personality.

Nanditha, V., Sinha, M., et al. (2020). Neuro-cognitive profile of chronotypes. J Cognitive Neuroscience.

Roenneberg, T., & Merrow, M. (2007). Munich Chronotype Questionnaire. Behavioral Sleep Medicine.

Schmidt, C., Collette, F., et al. (2015). Chronotype and cognitive synchrony effects. Chronobiology International.

Skene, D. J. (2025). PER3 polymorphisms and diurnal preference.

Song, Y., et al. (2023). The effect of chronotype on risk-taking behavior. Frontiers in Psychology.

Venkat, N., et al. (2020). Neuro-Cognitive profile of chronotypes at different times of day. Neuroscience and Medicine.

Zhang, Y., Folarin, A. A., et al. (2023). Longitudinal wearable study: seasonal and depression on circadian rhythms. arXiv.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, July 2). What is Chronotypes and 6 Important Ways to Re-Set Your Biological Clock. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/chronotypes/

Pingback: URL

Pingback: Lawfirm in bangkok

Pingback: 카지노비제이