Introduction

California wildfires specially Los Angeles wildfires have escalated in frequency and intensity, driven largely by human-induced climate change and unsustainable behaviors. While natural factors like drought and heatwaves contribute to fire risks, human activities—such as poorly managed land use, unsafe construction, irresponsible fire use, and carbon emissions—play a significant role in fueling wildfires. Addressing these behaviors requires more than policy enforcement; it demands an understanding of the psychology behind why people engage in unsustainable practices and how to encourage more sustainable choices.

The Role of Human Behavior in Wildfire Risk

Human activities directly and indirectly contribute to wildfires in several ways-

1.Urban Expansion into Fire-Prone Areas- More people are building homes in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), areas where human development meets undeveloped land, increasing fire risks (Radeloff et al., 2018).

2.Unsustainable Land Management- Fire suppression policies that prevent natural, smaller fires lead to fuel accumulation, making fires more destructive when they do occur (Pyne, 2019).

3.Human Ignition Sources- Approximately 85% of wildfires in the U.S. are caused by human activities, including unattended campfires, discarded cigarettes, fireworks, and power line failures (Balch et al., 2017).

4.Climate Change and Fossil Fuel Dependence- The burning of fossil fuels contributes to rising temperatures and drier conditions, which make wildfires more frequent and severe (IPCC, 2021).

Understanding why people continue to engage in these behaviors despite the known risks is key to designing effective interventions.

Read More- Mental Health

Psychological Impacts of Wildfires

Wildfires are a traumatic event that can cause serious damage to psychological and physical health, they cause problems like-

1. Trauma and Stress Disorders- Wildfires expose individuals to intense trauma, whether through direct exposure to the flames, displacement, or witnessing the destruction of homes and communities. PTSD, anxiety, and depression are common psychological responses to such experiences.

For instance, a study by Marshall et al. (2020) on survivors of the 2018 Camp Fire found that over 40% exhibited symptoms of PTSD a year after the event. The loss of a sense of safety, coupled with the unpredictability of future disasters, intensifies these disorders.

2. Anxiety and Climate Grief- In addition to acute trauma, wildfires contribute to broader psychological phenomena like climate anxiety and climate grief.

Climate anxiety refers to chronic fear and worry about environmental changes and their implications for future generations. According to Clayton and Karazsia (2020), climate anxiety affects individuals’ mental health and motivates sustainable behaviors, albeit inconsistently.

Climate grief, on the other hand, encapsulates feelings of sadness, loss, and helplessness in response to environmental degradation. These feelings are amplified in California, where the recurrence of wildfires leaves communities mourning lost natural beauty, biodiversity, and homes.

3. Community-Level Impacts- Psychologically, wildfires do not affect individuals in isolation—they disrupt entire communities. Shared trauma can lead to collective grief but also foster resilience through community solidarity. Altruistic behavior, such as volunteering and mutual aid, often emerges in response to disasters (Solnit, 2010). However, prolonged exposure to such crises can erode community bonds, leading to social fragmentation and mistrust in institutions tasked with prevention and recovery.

Read More- Psychology of Sustainability

Psychological Strategies to Promote Sustainable Behaviors

Some ways to promote sustainable behaviour include-

1. Framing and Messaging to Overcome Cognitive Biases

To counter optimism bias and normalcy bias, wildfire prevention messaging should emphasize personal relevance and immediacy. Research shows that people respond more strongly to messages that highlight direct risks to their homes and families rather than abstract statistics (Spence & Pidgeon, 2010).

For example, instead of stating, “California wildfires are increasing due to climate change,” a more effective message would be:

“Your home is in a high-risk wildfire zone. Taking these steps today can prevent disaster tomorrow.”

Additionally, using vivid storytelling and survivor testimonials can make the risk feel more real and emotionally engaging.

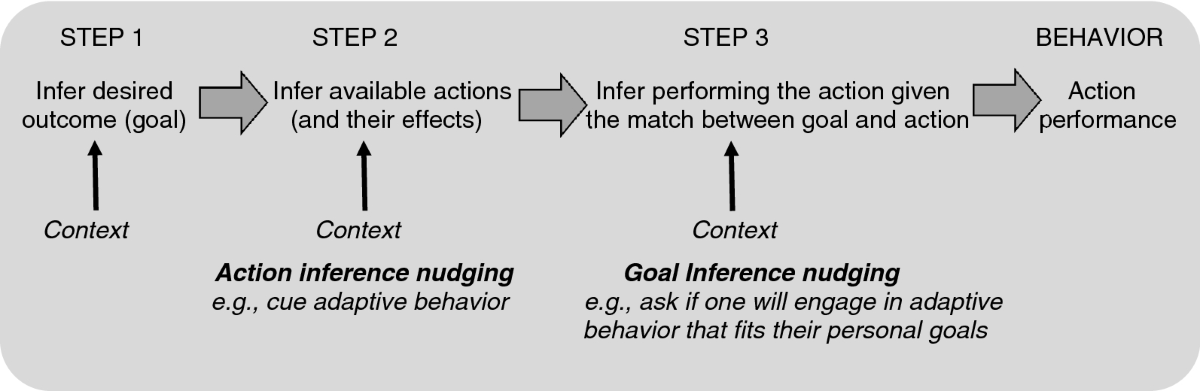

2. Nudging Sustainable Behavior

Behavioral “nudges” can subtly encourage fire-safe choices without restricting personal freedom (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Examples include-

- Default options- Making fire-resistant materials the default option in new housing developments.

- Salience cues- Placing warning signs in high-risk areas that visually demonstrate past fire damage.

- Commitment devices- Encouraging homeowners to publicly pledge to create defensible spaces, leveraging their commitment to follow through.

3. Incentives and Social Norms

People are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors when they see others doing the same. Social norm-based strategies include:

- Publicizing community participation rates- “85% of residents in your neighborhood have created defensible spaces—join them today!”

- Recognizing local leaders- Showcasing individuals who adopt sustainable behaviors can inspire others to follow suit.

- Financial incentives- Providing tax breaks or rebates for homeowners who implement fire-resistant landscaping and construction.

4. Overcoming the Tragedy of the Commons through Collective Action

To address the tragedy of the commons, collective responsibility must be emphasized. Community-based programs that encourage shared responsibility for fire safety—such as neighborhood fire-prevention teams—can increase cooperation (Ostrom, 1990).

For example, “Firewise USA” is a community-driven program that helps neighborhoods develop wildfire mitigation plans, demonstrating that shared action can lead to meaningful change.

5. Addressing Temporal Discounting through Immediate Benefits

To counteract short-term thinking, interventions should highlight immediate benefits rather than long-term risk reduction. For instance:

- Instead of emphasizing “fire protection in the next decade,” messaging could focus on lower insurance premiums, reduced property maintenance costs, and improved air quality from sustainable practices.

- Programs that provide instant rewards, such as free fire-resistant plants for creating defensible spaces, can encourage participation.

6. Education and Empowerment

Building self-efficacy—the belief that one’s actions can make a difference—is crucial for sustained behavior change (Bandura, 1977). Providing hands-on training, such as fire-safety workshops and interactive simulations, can empower individuals to take action.

Additionally, climate change education should emphasize solutions rather than just problems. When people see tangible steps they can take, they are more likely to feel motivated to act.

Conclusion

Wildfire prevention is not just an environmental or policy issue—it is a psychological challenge. Cognitive biases, habits, social norms, and short-term thinking all contribute to unsustainable behaviors that increase wildfire risks. By leveraging insights from psychology, we can design more effective interventions to promote fire-safe behaviors.

Through targeted messaging, behavioral nudges, incentives, collective action, and education, communities can shift toward sustainable practices that reduce wildfire risks. Addressing the psychological barriers to change is not only crucial for preventing disasters but also for fostering long-term environmental resilience.

References

Balch, J. K., Bradley, B. A., Abatzoglou, J. T., Nagy, R. C., Fusco, E. J., & Mahood, A. L. (2017). Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(11), 2946-2951.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015-1026.

Clayton, S., & Karazsia, B. T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243-1248.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

Marshall, G. N., Schell, T. L., Elliott, M. N., Rayburn, N. R., & Jaycox, L. H. (2020). Psychiatric disorders among adults seeking emergency disaster assistance after a wildland-urban interface fire. Psychiatric Services, 71(2), 133-141. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000026

National Interagency Fire Center. (2021). Statistics on wildfires. Retrieved from https://www.nifc.gov/

Solnit, R. (2010). A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. Penguin Books.

Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,022 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, January 12). California Wildfires and 6 Ways to Promote Sustainable Behaviour. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/california-wildfires/

Pingback: 8 Important Ways for Sustainable Living - PsychUniverse