Adolescence is often described as a time of chaos, curiosity, and transformation. It’s the stage where emotions run high, impulses take over, and every experience feels amplified. Parents might call it a “phase,” but neuroscience calls it something far more fascinating — a period of profound brain remodeling.

Between roughly ages 12 and 25, the human brain undergoes a complex process of rewiring that affects decision-making, risk-taking, and emotional regulation. What appears as recklessness or moodiness from the outside is, in fact, the brain learning how to become an independent, adaptable adult.

Read More: Emotions SOS

A Brain Under Construction

For most of history, adolescence was viewed primarily as a psychological or social phase. But modern brain imaging tells a deeper story: the adolescent brain is a literal construction zone.

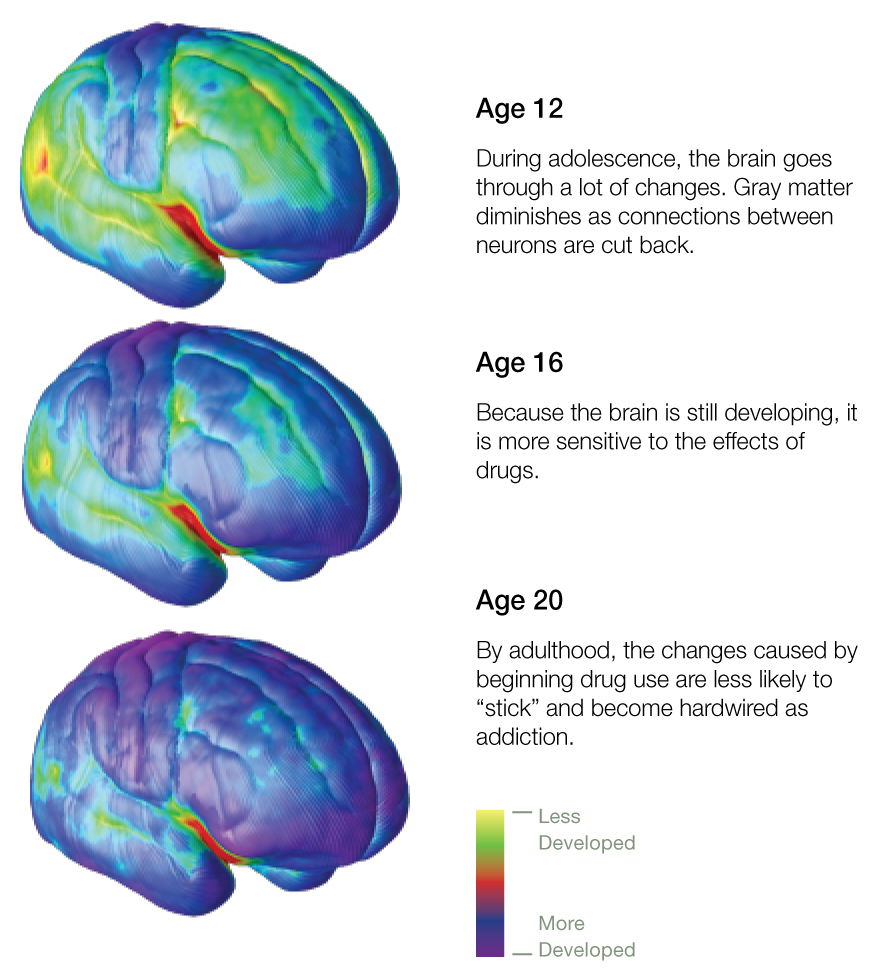

According to neuroscientist Jay Giedd (2004), the brain doesn’t fully mature until the mid-20s. During adolescence, neural pathways are being strengthened or pruned away based on experience. This process, known as synaptic pruning, ensures that the brain becomes more efficient — “use it or lose it” applies here in a very real sense.

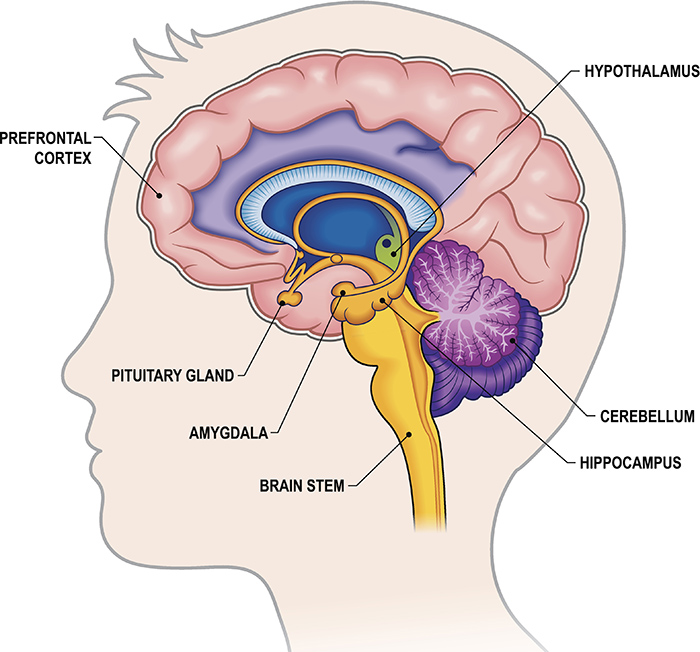

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning, planning, and impulse control, is one of the last areas to fully develop. Meanwhile, the limbic system, which drives emotions and reward-seeking, is already active and powerful. The result? A brain built for exploration and novelty, but not yet equipped for full self-regulation.

The Emotional Storm

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, plays a central role in processing emotions and rewards. In adolescents, these regions are hypersensitive.

This heightened emotional response means that teens experience both pleasure and pain more intensely than adults (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008). The thrill of a rollercoaster, the sting of rejection, the rush of friendship — everything feels bigger.

Dopamine, the brain’s “feel-good” neurotransmitter, spikes more dramatically during adolescence (Galván, 2010). That surge makes rewarding experiences — like social approval, risk-taking, or success — feel intoxicating. But it also means that boredom can feel unbearable.

Why Teens Take Risks

From sneaking out to trying new challenges, risk-taking is almost a hallmark of adolescence. But why?

The key lies in the imbalance between the emotional limbic system and the still-maturing prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex helps us weigh consequences and resist impulses, but in teens, this “brake system” isn’t fully functional yet (Steinberg, 2010).

At the same time, social approval and peer feedback are extremely rewarding to the adolescent brain. Studies using fMRI scans show that teens take significantly more risks when peers are watching than when they’re alone (Chein et al., 2011).

So, risk-taking isn’t just rebellion — it’s neurologically encouraged exploration. Evolutionarily, it makes sense: risk and novelty help young people leave the safety of family and learn independence.

Sleep, Stress, and the Teenage Mind

One of the least appreciated aspects of the adolescent brain is how it processes sleep and stress.

Teens experience a shift in circadian rhythm that makes them naturally inclined to fall asleep and wake up later (Carskadon, 2011). Early school start times often clash with this biological clock, leading to chronic sleep deprivation — which can impair memory, mood, and focus.

At the same time, the stress response system (HPA axis) is particularly sensitive during adolescence. Elevated cortisol levels can make emotional ups and downs feel more extreme. Chronic stress during this period can even alter brain development, especially in regions related to emotion and learning (Romeo, 2013).

The Social Brain

If adolescence had a soundtrack, it would be social — filled with friends, relationships, and identity formation.

The adolescent brain is wired to prioritize social belonging. Evolutionarily, this made sense: learning to fit into a social group increased survival chances. Neuroscientific studies show that rejection activates the same pain circuits in the brain as physical injury (Eisenberger, 2012). That’s why a breakup or social exclusion can feel devastating to a teen.

Social media amplifies this neural sensitivity. Every like, comment, or notification delivers a small dopamine hit, reinforcing social feedback loops. Understanding this mechanism helps explain why digital validation can become addictive for adolescents.

Learning and the Adolescent Brain

Adolescence is not just a time of emotional turbulence — it’s also a time of extraordinary learning potential.

The adolescent brain’s plasticity makes it especially adaptable. New skills, languages, and experiences are absorbed more efficiently during this period than in adulthood (Luna et al., 2015). This flexibility comes from ongoing neural remodeling — the brain is fine-tuning its connections for the adult world.

However, this same plasticity means that negative influences (chronic stress, substance use, poor sleep) can have lasting effects. The habits formed in adolescence lay the foundation for lifelong behaviors.

The Role of Identity and Independence

Adolescence is also the time when individuals begin forming a sense of self. Psychologist Erik Erikson (1968) described this as the stage of identity vs. role confusion — a critical period when young people explore beliefs, values, and goals.

The developing prefrontal cortex enables abstract thinking and moral reasoning, allowing teens to question authority and envision future possibilities. While this can lead to conflict with parents, it’s also what drives creativity, innovation, and autonomy.

In essence, the turmoil of adolescence is the brain’s way of sculpting an independent mind.

The Myth of the “Crazy Teen”

Despite cultural stereotypes, teens are not irrational or broken — they are learning machines, programmed for growth and exploration. Their heightened emotions and risk-taking behaviors have evolutionary value: they push boundaries, seek novelty, and learn from mistakes.

Neuroscientist Laurence Steinberg (2014) argues that adolescence should be understood as a time of opportunity rather than chaos. Supporting teens through this developmental phase — rather than punishing their impulsivity — leads to better outcomes.

When adults provide structure, empathy, and open communication, adolescents learn to harness their emotional energy for creativity and self-discovery.

Nurturing the Adolescent Brain

So, what helps teens thrive during this pivotal stage? Research points to a few key factors:

-

Sleep: Allowing later wake times aligns with natural circadian rhythms and improves focus and mood (Carskadon, 2011).

-

Supportive Relationships: Strong connections with adults buffer stress and promote emotional regulation (Allen & Miga, 2010).

-

Opportunities for Risk — Safely: Sports, arts, travel, and leadership opportunities channel the adolescent drive for novelty into healthy growth.

-

Mindfulness and Emotional Education: Teaching awareness and coping strategies strengthens prefrontal-limbic connections (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

-

Balanced Technology Use: Encouraging moderation and digital literacy helps teens manage the social feedback loop of online life.

The Power and Promise of the Teenage Brain

The teenage brain is not broken — it’s brilliant. It’s wired for passion, creativity, and social connection. The same sensitivity that makes adolescence tumultuous also makes it transformative.

When society understands this stage as a biological and psychological opportunity rather than a problem, we can better support teens in developing confidence, resilience, and wisdom.

As neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore (2018) puts it, adolescence is a “window of opportunity” — a time when the brain is learning how to be human in all its complexity.

References

Allen, J. P., & Miga, E. M. (2010). Attachment in adolescence: A move to the level of emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 181–190.

Blakemore, S.-J. (2018). Inventing ourselves: The secret life of the teenage brain. PublicAffairs.

Carskadon, M. A. (2011). Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 58(3), 637–647.

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111–126.

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk-taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1–F10.

Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The pain of social disconnection: Examining the shared neural underpinnings of physical and social pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(6), 421–434.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

Galván, A. (2010). Adolescent development of the reward system. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 6.

Giedd, J. N. (2004). Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 77–85.

Luna, B., Marek, S., Larsen, B., Tervo-Clemmens, B., & Chahal, R. (2015). An integrative model of the maturation of cognitive control. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 151–170.

Romeo, R. D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 140–145.

Steinberg, L. (2010). A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 216–224.

Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 17). The Adolescent Brain and 5 Important Ways to Nurture It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/adolescent-brain/