Introduction

Remote work has transformed the way millions of people experience their jobs. What began as a temporary response to global disruption has become a permanent feature of modern work culture. For many, working from home offers freedom, flexibility, and autonomy. For others, it brings isolation, blurred boundaries, and emotional exhaustion.

From a psychological standpoint, remote work is not simply a change in location—it is a profound shift in how people think, feel, and relate to their work and colleagues.

Read More: Teenagers and Risk

Autonomy and Control

One of the most significant psychological benefits of remote work is increased autonomy. Employees often have more control over their schedules, work environment, and daily routines.

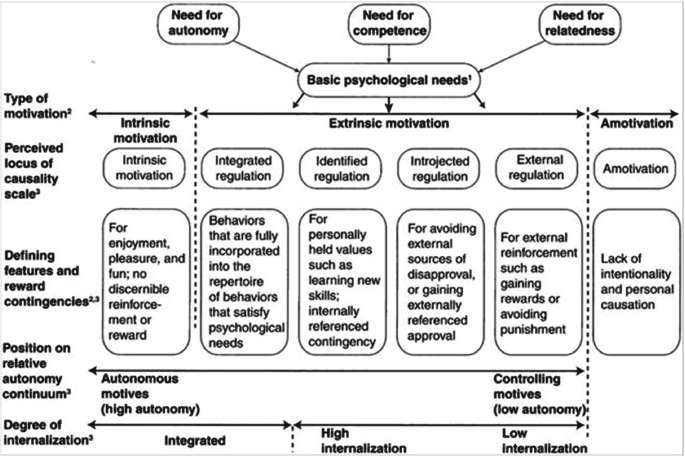

According to Self-Determination Theory, autonomy is a core psychological need linked to motivation and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000). When people feel trusted to manage their own time, they often experience:

- Greater job satisfaction

- Higher intrinsic motivation

- Reduced stress related to micromanagement

For many workers, this sense of control leads to improved mental health and productivity.

Reduced Commuting Stress and Cognitive Load

Commuting is a major but often underestimated source of psychological strain. Long or unpredictable commutes are associated with:

- Increased stress hormones

- Fatigue

- Lower life satisfaction

Remote work eliminates or reduces this burden, freeing cognitive and emotional resources. Studies have found that employees who avoid long commutes report better mood and greater overall well-being (Clark et al., 2020).

The time saved is often reallocated to sleep, exercise, or family, all of which support mental health.

Isolation and Loneliness

Despite its benefits, remote work can increase social isolation, a known risk factor for poor mental health.

Humans are inherently social beings. Daily workplace interactions—casual conversations, shared lunches, spontaneous collaboration—serve important psychological functions. When these interactions disappear, employees may experience:

- Loneliness

- Disconnection

- Reduced sense of belonging

Research shows that prolonged social isolation is linked to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015).

For individuals living alone or working fully remotely, this emotional toll can be significant.

Blurred Boundaries and Work-Life Imbalance

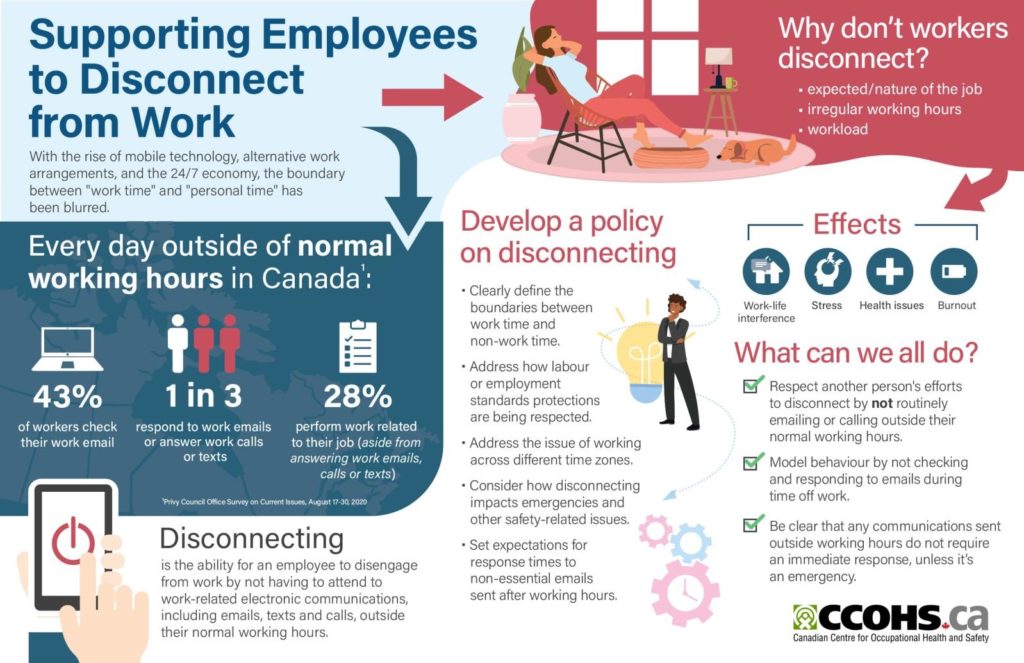

One of the most common psychological challenges of remote work is the blurring of boundaries between work and personal life.

Without physical separation between office and home:

- Work hours may extend unintentionally

- Employees may feel pressure to be constantly available

- Recovery time is reduced

This phenomenon, often referred to as boundary erosion, increases the risk of burnout. Research indicates that difficulty detaching from work is strongly associated with emotional exhaustion and sleep problems (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015).

Digital Fatigue and Cognitive Overload

Remote work relies heavily on digital communication—video calls, emails, messaging platforms. While efficient, these tools come with psychological costs.

Video meetings, in particular, can cause:

- Increased self-monitoring

- Reduced nonverbal cues

- Sustained attention demands

This contributes to what researchers call “Zoom fatigue”, a form of mental exhaustion linked to prolonged virtual interaction (Bailenson, 2021).

Multitasking across digital platforms further increases cognitive load and stress.

Productivity Pressure and the “Always-On” Culture

Remote workers often feel the need to prove they are working, leading to overwork.

Psychologically, this pressure is fueled by:

- Visibility concerns

- Fear of being perceived as less committed

- Lack of clear performance boundaries

Studies suggest that remote workers may work longer hours than their in-office counterparts, increasing the risk of chronic stress and burnout (Eurofound & ILO, 2017).

Individual Differences Matter

The mental impact of remote work is not universal. Personality and personal circumstances play a crucial role.

- Introverts may thrive with reduced social stimulation

- Extroverts may struggle with limited interaction

- People with caregiving responsibilities may experience added stress

- Those with supportive home environments often fare better

Psychological flexibility and coping skills significantly influence how individuals adapt to remote work conditions.

Remote Work and Mental Health Inequality

Remote work can exacerbate existing inequalities. Not all employees have:

- Quiet workspaces

- Reliable technology

- Supportive home environments

These disparities can increase stress and reduce well-being, particularly for younger workers, women, and marginalized groups.

Psychologically, unequal access to resources undermines perceived fairness and control, both critical for mental health.

The Role of Leadership in Remote Mental Health

Leadership plays a decisive role in shaping the mental impact of remote work.

Supportive leaders:

- Set clear expectations

- Respect boundaries

- Encourage breaks and time off

- Normalize conversations about mental health

Research shows that perceived organizational support buffers stress and reduces burnout in remote settings (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Strategies to Protect Mental Well-Being in Remote Work

Psychological research suggests several effective strategies:

For Individuals:

- Establish clear work hours

- Create physical or symbolic boundaries

- Schedule social interaction

- Take regular breaks from screens

For Organizations:

- Promote flexible but bounded schedules

- Reduce unnecessary meetings

- Encourage asynchronous communication

- Provide mental health resources

These strategies help restore balance and psychological safety.

The Hybrid Future

Many organizations are adopting hybrid work models, combining remote and in-person work. From a psychological perspective, hybrid models offer the best of both worlds:

- Autonomy and flexibility

- Social connection and collaboration

When designed thoughtfully, hybrid work can support both productivity and mental health.

Conclusion

Remote work is not inherently good or bad—it is a psychological experiment unfolding in real time. Its impact depends on structure, support, personality, and culture.

Understanding the mental effects of remote work allows individuals and organizations to make informed choices. With intentional design and psychological awareness, remote work can become not just sustainable—but mentally healthy.

References

Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2(1).

Clark, B., Chatterjee, K., & Martin, A. (2020). Commuting and well-being. Travel Behaviour and Society, 20, 41–55.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Eurofound & International Labour Organization. (2017). Working anytime, anywhere.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

Men, L. R. (2014). Strategic internal communication. Public Relations Journal, 8(2).

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 26). 6 Important Mental Impact of Remote Work. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/mental-impact-of-remote-work/