Teenagers have a reputation for risk-taking. From reckless driving and substance use to impulsive decisions and emotional volatility, adolescence is often framed as a period of poor judgment. Popular culture portrays teens as irrational, irresponsible, or incapable of thinking ahead.

But neuroscience tells a very different story.

Teenage risk-taking is not a flaw in character or a failure of parenting. It is the predictable result of a developing brain undergoing profound structural and functional changes. Understanding why adolescents take risks requires looking beyond behavior and into the brain systems that shape motivation, reward, emotion, and self-control.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Adolescence

Adolescence is not merely a transition between childhood and adulthood—it is a distinct developmental stage with its own neurobiological profile.

During this period, the brain undergoes:

- extensive synaptic pruning

- increased myelination

- reorganization of neural networks

- heightened sensitivity to social and emotional stimuli

These changes prepare the individual for independence, exploration, and adaptation to complex social environments.

Risk-taking is not an accident—it is part of this developmental agenda.

The Dual Systems Model of the Adolescent Brain

One of the most influential frameworks for understanding teenage behavior is the dual systems model (Steinberg, 2008).

According to this model, two major brain systems develop on different timelines:

The Socioemotional (Reward) System

- Centered in the limbic system

- Includes the nucleus accumbens and amygdala

- Highly sensitive to rewards, novelty, and emotional stimuli

The Cognitive Control System

- Centered in the prefrontal cortex

- Responsible for impulse control, planning, and long-term thinking

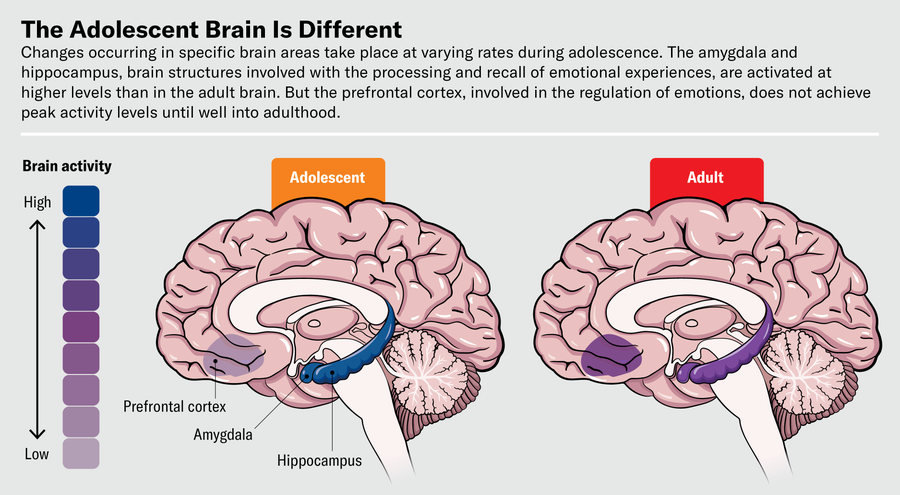

During adolescence, the reward system matures earlier and faster than the control system. This creates a developmental imbalance.

The result:

Strong motivation and emotional drive with still-developing brakes.

Dopamine and Reward Sensitivity in Teenagers

Adolescents experience heightened dopamine activity in response to rewards. Dopamine drives motivation, novelty-seeking, and learning from experience.

Research shows that teenagers:

-

experience stronger reward signals than children or adults

-

are more motivated by immediate rewards

-

show increased neural activation in reward centers during risk-taking

This heightened sensitivity encourages exploration and learning—but also increases risk-taking, especially in emotionally charged contexts (Galván et al., 2006).

The Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex—the brain region responsible for:

- impulse control

- future planning

- weighing consequences

- emotional regulation

continues developing well into the mid-to-late 20s.

This does not mean teenagers lack reasoning ability. In calm, structured situations, adolescents can reason as well as adults. The challenge arises in emotionally intense or social situations, where the reward system overwhelms cognitive control.

This explains why teens may:

- make thoughtful decisions in class

- act impulsively with peers

- understand risks but still take them

Knowledge alone does not override neural imbalance.

The Powerful Influence of Peers

One of the most striking findings in adolescent neuroscience is the effect of peer presence.

Studies show that adolescents take significantly more risks when peers are present—even if peers are only observing (Chein et al., 2011).

Neuroimaging reveals that peer presence:

- increases reward system activation

- amplifies perceived benefits of risky behavior

- reduces sensitivity to potential negative outcomes

From an evolutionary perspective, peer acceptance was crucial for survival. The teenage brain is wired to prioritize social belonging.

Risk-Taking Is Not Always Negative

While often framed as dangerous, risk-taking also serves adaptive purposes.

Healthy risk-taking supports:

- independence

- identity exploration

- learning from experience

- creativity and innovation

- resilience building

Many positive adult traits—entrepreneurship, leadership, exploration—emerge from the same neural systems that drive adolescent risk-taking.

The problem is not risk itself, but unsafe, unsupported, or chronic risk.

Emotional Intensity and the Adolescent Brain

Teenagers experience emotions more intensely than adults. This is not exaggeration—it is neurobiological reality.

The amygdala, which processes emotional significance, is highly reactive during adolescence. At the same time, regulatory connections to the prefrontal cortex are still developing.

This combination leads to:

- heightened emotional reactions

- rapid mood shifts

- impulsive responses under stress

Strong emotions can temporarily override rational thinking.

Stress, Sleep, and Risk-Taking

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to sleep deprivation due to:

- biological shifts in circadian rhythm

- early school start times

- increased academic and social demands

Sleep deprivation impairs:

- impulse control

- emotional regulation

- decision-making

Studies show that tired adolescents engage in more risk-taking and show reduced prefrontal functioning (Carskadon, 2011).

Stress further amplifies reward-seeking and impulsivity.

Substance Use and the Developing Brain

Because the adolescent brain is still developing, it is more vulnerable to the effects of substances.

Early substance use can:

- alter reward sensitivity

- interfere with neural pruning

- increase addiction risk

- impair learning and memory

This vulnerability is why prevention efforts emphasize delaying substance use rather than relying solely on education.

Why Fear-Based Approaches Don’t Work

Traditional approaches to teenage risk often rely on:

- scare tactics

- punishment

- lectures

- strict control

Neuroscience suggests these methods are largely ineffective. Fear-based messaging activates emotional systems without strengthening cognitive control.

What works better:

- supportive relationships

- clear boundaries

- open communication

- gradual autonomy

Adolescents are more receptive to guidance from adults they trust.

Supporting Healthy Decision-Making

Adults can support adolescent development by:

- Providing Structure Without Overcontrol: Clear rules combined with autonomy foster responsibility.

- Teaching Skills, Not Just Rules: Problem-solving, emotional regulation, and decision-making skills strengthen the prefrontal cortex.

- Encouraging Safe Risks: Sports, creative pursuits, leadership roles, and challenges provide outlets for exploration.

- Modeling Regulation: Adults’ emotional responses shape adolescents’ regulatory skills.

Individual Differences in Risk-Taking

Not all teens take the same risks. Risk-taking varies based on:

- temperament

- genetics

- trauma history

- peer environment

- mental health

Understanding these differences prevents overgeneralization and stigma.

When Risk-Taking Becomes Concerning

Risk-taking warrants intervention when it:

- is persistent and escalating

- interferes with functioning

- involves significant harm

- occurs alongside mental health issues

Early intervention is more effective than punishment.

Conclusion

Teenage risk-taking is not evidence of a broken brain—it is evidence of a developing one. Adolescents are neurologically wired to seek novelty, rewards, and social connection before their impulse control systems fully mature.

Understanding the neuroscience behind teenage behavior allows adults to respond with guidance rather than fear, support rather than control. When adolescents are given structure, trust, and opportunities for healthy exploration, risk-taking becomes a pathway to growth rather than harm.

The teenage brain is not deficient—it is under construction.

References

Carskadon, M. A. (2011). Sleep in adolescents. Sleep Medicine.

Chein, J., et al. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking. Developmental Science.

Galván, A., et al. (2006). Earlier development of the accumbens relative to orbitofrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience.

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review.

Casey, B. J., et al. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 19). Why Teenagers Take Risks and 4 Important Supporting Healthy Decision-Making. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/teenagers-take-risks/

Pingback: The Psychology of Christmas Traditions and 9 Important Reasons Why Traditions Make Us Feel Good - PsychUniverse