Few topics in child psychology provoke as much anxiety as screen time. Parents are warned that screens will damage attention spans, reduce empathy, impair brain development, and replace real-world relationships. Headlines often frame screens as an unprecedented threat to childhood—comparing smartphones to addictive drugs and predicting cognitive decline.

Yet psychological research paints a far more nuanced picture. Screens are not inherently harmful, nor are they universally beneficial. Their impact depends on how, why, when, and with whom they are used. Understanding what research actually shows—rather than what fear-driven narratives suggest—is essential for making informed decisions about children’s media use.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Why Screen Time Became a Moral Panic

Every generation fears new technology. Radio, television, video games, and even novels were once accused of corrupting youth. Screens are simply the latest target.

Psychologically, moral panics emerge when:

- technology changes rapidly

- adults feel excluded from children’s experiences

- long-term effects are uncertain

- anecdotes overshadow data

Screens symbolize loss of control and changing norms. This emotional response often precedes scientific consensus.

What “Screen Time” Actually Includes

One major flaw in public debates is treating screen time as a single, uniform activity. Research distinguishes between:

- Passive consumption (watching videos)

- Interactive use (games, learning apps)

- Social connection (video calls, messaging)

- Creative use (drawing, coding, storytelling)

These activities engage the brain in very different ways.

A child video-chatting with grandparents activates social and linguistic networks, while passively watching fast-paced cartoons engages attention differently. Lumping these together distorts conclusions.

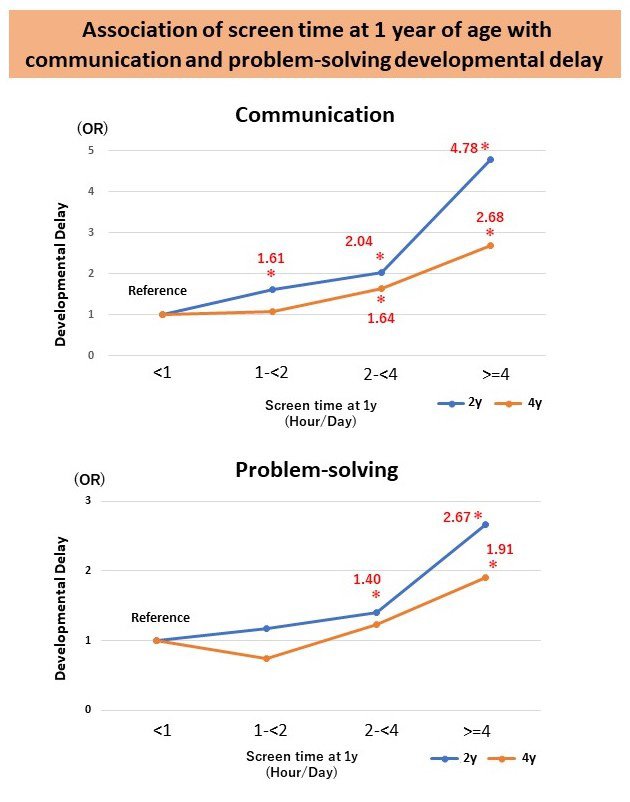

1. What Research Says About Brain Development

One of the most common fears is that screens damage the developing brain. Neuroimaging studies, however, show no evidence that moderate screen use causes structural brain harm.

Large-scale studies suggest:

- No consistent link between screen time and reduced intelligence

- No evidence of “brain damage” from screens

- Weak correlations between excessive screen use and attention difficulties

A landmark study by Orben & Przybylski (2019) found that digital technology use explained less than 1% of variation in adolescent well-being.

In other words: screens are not the dominant force shaping cognitive development.

2. Attention Spans

Screens are often blamed for attention problems. However, psychology distinguishes between correlation and causation.

Children with:

- ADHD traits

- impulsivity

- emotional dysregulation

are more likely to gravitate toward screens. Screens may reflect underlying attention differences rather than cause them.

Longitudinal studies show mixed results. When socioeconomic factors, parenting stress, sleep, and mental health are controlled, the association between screen time and attention problems significantly weakens (Domingues-Montanari, 2017).

3. The Role of Content Over Quantity

Research consistently shows that content matters more than total hours.

High-quality educational content can:

- support language development

- enhance problem-solving

- reinforce learning

Conversely, fast-paced, overstimulating content may increase short-term arousal without long-term benefit.

Christakis et al. (2004) found that extremely fast-paced content may temporarily affect attention in very young children—but effects were small and context-dependent.

4. Social Development and Screens

A common fear is that screens replace social interaction. Yet screens increasingly facilitate social connection.

Children use screens to:

- collaborate in games

- maintain friendships

- communicate with distant relatives

- explore identity

During adolescence, digital communication supports peer bonding rather than replacing it (Odgers & Jensen, 2020).

The risk arises not from screens themselves, but from social deprivation, which can occur with or without technology.

5. Screen Time and Emotional Well-Being

High screen use correlates with increased anxiety and depression—but again, causality is unclear.

Children experiencing:

- stress

- loneliness

- family conflict

- emotional dysregulation

often turn to screens for comfort and distraction. Screens may serve as coping tools rather than causes of distress.

Importantly, moderate screen use shows no consistent negative mental-health impact in most studies.

6. The Importance of Context and Co-Viewing

One of the strongest protective factors is adult involvement.

When caregivers:

- watch with children

- discuss content

- set predictable boundaries

- model healthy use

negative effects decrease significantly.

Co-viewing turns screen time into a relational experience rather than isolation.

7. Socioeconomic Factors Matter More Than Screens

Research consistently shows that:

- poverty

- parental stress

- lack of access to resources

- neighborhood safety

have far greater impacts on child development than screen exposure.

Focusing solely on screens can distract from more powerful determinants of well-being.

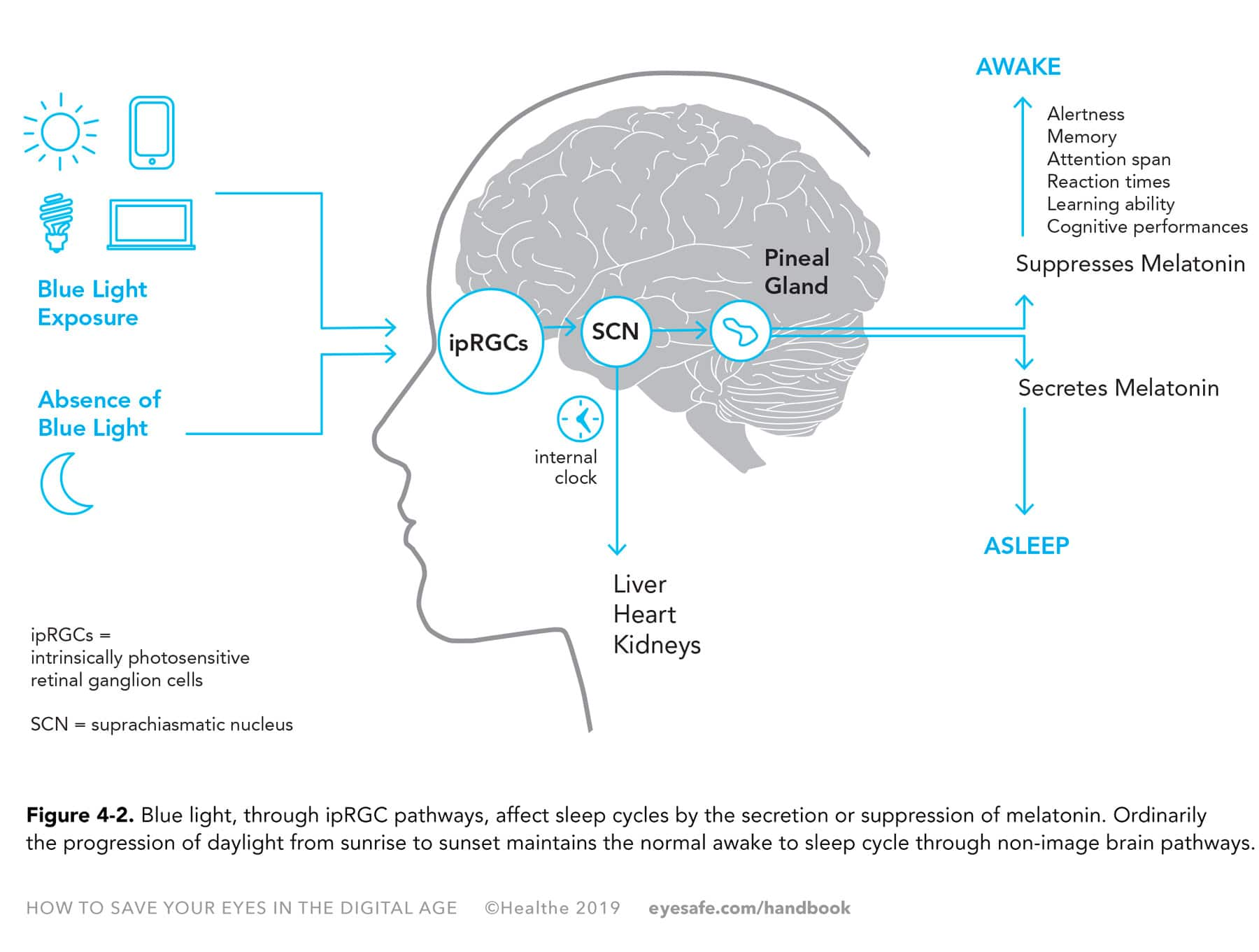

8. Sleep Is the Real Issue

If screens harm children, it is most often through sleep disruption, not content itself.

Blue light exposure and late-night use can:

- delay melatonin release

- reduce sleep duration

- impair emotional regulation

Sleep deprivation—not screens per se—is linked to mood, attention, and learning difficulties.

What Research-Based Guidelines Recommend

Evidence-based recommendations emphasize:

- age-appropriate content

- consistent routines

- device-free sleep times

- balance with physical activity

- quality over quantity

The American Academy of Pediatrics now advocates flexible, individualized media plans rather than strict time limits.

Screens Are Tools, Not Villains

Technology reflects how it is used. Screens can:

- educate

- connect

- soothe

- entertain

- create

They can also distract or overstimulate. The difference lies in guidance, balance, and context—not fear.

Conclusion

The science is clear: screens are not inherently harmful to children. Moderate, intentional use—especially when guided by caregivers—poses minimal risk and may offer benefits. Moral panic oversimplifies a complex issue.

Rather than asking “How much screen time is too much?”, psychology suggests a better question:

“Is my child thriving emotionally, socially, and physically?”

Screens are only one small piece of that larger picture.

References

Christakis, D. A., et al. (2004). Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems. Pediatrics.

Domingues-Montanari, S. (2017). Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health.

Odgers, C. L., & Jensen, M. R. (2020). Annual research review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour.American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Media and young minds. Pediatrics.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 17). Screen Time and Kids With 8 Powerful Research Backed Evidences. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/screen-time-and-kids/