Overthinking is often praised as intelligence, depth, or conscientiousness. People who overthink are told they are “analytical,” “thoughtful,” or “detail-oriented.” Yet for millions, overthinking is not a strength—it is a mental trap that drains energy, increases anxiety, disrupts sleep, and interferes with decision-making and emotional well-being.

Psychologically, overthinking is not simply “thinking too much.” It is a maladaptive cognitive pattern driven by anxiety, threat perception, and faulty beliefs about control and certainty. Understanding why the brain overthinks—and how to interrupt the cycle—requires examining both cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

Read More: Hope Theory

What Is Overthinking?

Overthinking typically takes two primary forms:

- Rumination – repetitive thinking about past events, mistakes, or perceived failures

- Worry – repetitive thinking about future possibilities, threats, or uncertainties

Research shows that both are forms of repetitive negative thinking (RNT), a transdiagnostic process linked to anxiety disorders, depression, and stress-related conditions (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008).

Overthinking is not problem-solving. Unlike productive thinking, it:

- does not lead to action

- increases emotional distress

- narrows attention

- reinforces negative beliefs

- creates mental exhaustion

Ironically, the more someone overthinks, the less clarity they achieve.

Why the Brain Overthinks

The human brain evolved to detect threats and predict danger. From an evolutionary standpoint, anticipating problems increased survival. However, modern life presents abstract threats—social rejection, career uncertainty, financial stress—that the brain treats as physical danger.

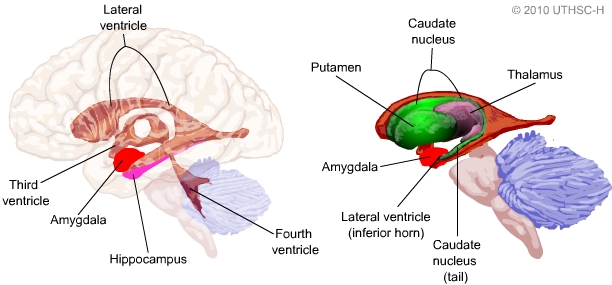

Overthinking emerges when the brain’s threat-detection system (amygdala) remains chronically activated. This activation:

- signals danger where none exists

- prioritizes uncertainty over resolution

- keeps the nervous system in a state of vigilance

The brain mistakenly believes that continuous thinking will prevent harm. In reality, it produces the opposite effect.

The Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty

One of the strongest predictors of overthinking is intolerance of uncertainty—the belief that not knowing is unacceptable or dangerous (Dugas et al., 1998).

People who overthink often hold assumptions such as:

- “If I think about this enough, I’ll prevent something bad.”

- “Not having certainty means I’m irresponsible.”

- “If I stop thinking, I’ll miss something important.”

These beliefs fuel endless mental loops. The brain keeps searching for certainty that does not exist.

Cognitive Traps That Sustain Overthinking

Overthinking is maintained by predictable cognitive distortions.

- Catastrophizing: Assuming the worst-case scenario is not only possible, but likely.

- All-or-Nothing Thinking: Viewing outcomes as total success or complete failure.

- Mind Reading: Assuming we know what others think—usually negatively.

- Emotional Reasoning: Believing that feeling anxious means something is wrong.

- Perfectionism: Believing that mistakes are intolerable and must be prevented at all costs.

These distortions are not signs of weakness—they are automatic mental shortcuts.

Control Paradox

Overthinking creates the illusion of control. But psychological research shows a paradox:

- The more someone tries to control uncertainty through thinking

- The more anxious and mentally rigid they become

This paradox explains why reassurance, analysis, and checking rarely reduce overthinking long-term. The brain learns that thinking is necessary for safety, reinforcing the cycle.

The Neurology of Overthinking

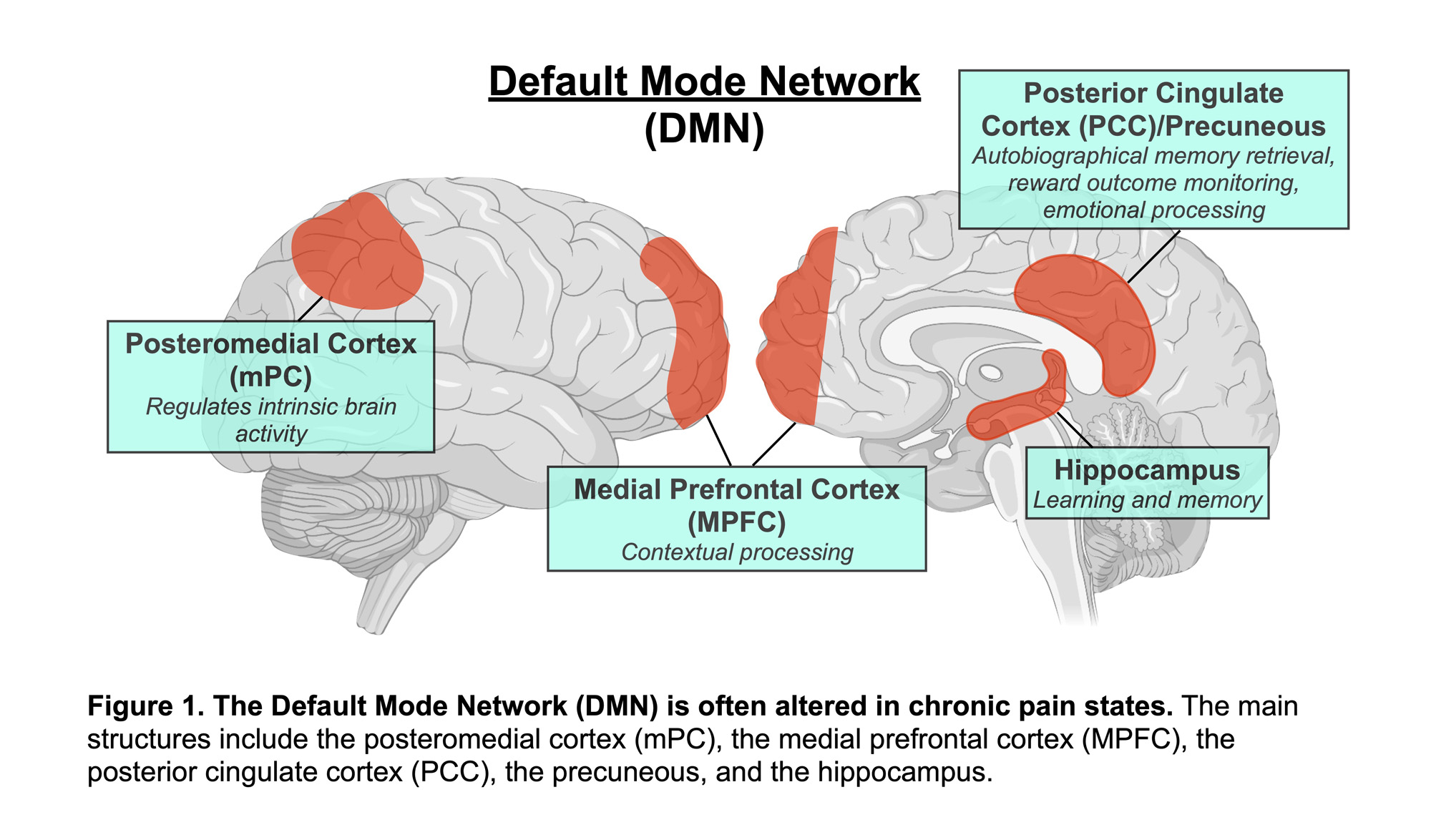

Neuroimaging studies show that chronic overthinking is associated with:

- increased activity in the default mode network (DMN)

- reduced flexibility in attention networks

- heightened amygdala reactivity

- reduced prefrontal regulation

The default mode network is involved in self-referential thought. When overactive, the mind becomes stuck in internal narratives rather than present-moment awareness.

Why Overthinking Feels Impossible to Stop

Many people try to “stop thinking,” which paradoxically increases thinking. Suppression activates monitoring processes that keep thoughts salient (Wegner, 1994).

This is why effective interventions focus not on eliminating thoughts, but changing the relationship to them.

Practical, Evidence-Based Interventions

Some interventions include:

1. Cognitive Defusion

Rather than arguing with thoughts, cognitive defusion teaches individuals to observe thoughts as mental events—not truths.

Example:

“I’m having the thought that something will go wrong.”

This small shift reduces emotional intensity.

2. Scheduled Worry Time

Research shows that limiting worry to a set time reduces its spread throughout the day.

- Write worries down

- Postpone thinking until scheduled time

- Train the brain that worry is not constant

3. Behavioral Activation

Overthinking thrives in inactivity. Action disrupts rumination by re-engaging the brain with the external world. Small, imperfect actions are more effective than waiting for clarity.

4. Tolerance of Uncertainty Training

Gradual exposure to uncertainty teaches the nervous system that ambiguity is survivable.

Examples include:

- delaying reassurance

- making decisions without overanalysis

- resisting checking behaviors

5. Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness reduces overthinking by anchoring attention in sensory experience rather than internal narrative. Meta-analyses show strong effects on rumination reduction (Hölzel et al., 2011).

When Overthinking Becomes Clinical

Chronic overthinking is a core feature of:

- generalized anxiety disorder

- major depressive disorder

- obsessive-compulsive disorder

- trauma-related disorders

When overthinking interferes with sleep, relationships, or functioning, professional intervention is recommended.

Conclusion

Overthinking is not a personality flaw or intellectual strength gone wrong. It is a learned response to uncertainty, fear, and the belief that thinking equals safety. By understanding the cognitive traps that sustain it and applying evidence-based interventions, individuals can reduce mental noise and restore psychological flexibility.

The goal is not to stop thinking—but to think less fearfully and live more fully.

References

Dugas, M. J., et al. (1998). Intolerance of uncertainty and worry. Journal of Anxiety Disorders.

Hölzel, B. K., et al. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., et al. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,049 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 15). The Psychology of Overthinking and 2 Important Forms of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-overthinking/

Pingback: 5 First Impression Tips to Make a Lasting Impact - PsychUniverse