Introduction

Technological acceleration is often celebrated as a hallmark of modern civilization. Faster devices, smarter algorithms, and more interconnected systems promise efficiency, pleasure, and convenience. Yet behind the glossy façade of perpetual innovation lies a quieter psychological reality: many people feel exhausted, overwhelmed, and chronically behind. This phenomenon—“future fatigue”—captures the emotional and cognitive costs of living in an environment of relentless technological change.

While the term is relatively new in popular discourse, its foundations lie in well-established psychological theories related to stress, cognitive load, neuroplasticity, and behavioral adaptation. In a world where digital ecosystems evolve at unprecedented speed, understanding the psychological toll of constant upgrading is essential for mental health, productivity, and wellbeing.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

The Acceleration of Technology and the Human Brain

The pace of technological change has outstripped the human brain’s evolutionary ability to adapt. While humans evolved in relatively stable environments over hundreds of thousands of years, the digital revolution has transformed cognitive environments within decades. Neuroscience demonstrates that human brains adapt well to incremental change but struggle with rapid, unpredictable shifts (Baumeister & Tierney, 2011). This mismatch between evolution and digital innovation creates persistent cognitive stress.

Constant novelty and dopamine cycles

New devices, apps, and operating systems stimulate novelty-seeking regions of the brain. Novelty triggers dopamine release, temporarily increasing motivation and attention (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015). However, in excess, novelty can produce a neurochemical rollercoaster. Constantly adapting to new interfaces and features shifts the brain into repeated cycles of reward anticipation and frustration, leading to eventual exhaustion when dopamine pathways become overstimulated.

Cognitive load and upgrade fatigue

Cognitive load theory states that working memory has limited capacity and becomes overwhelmed when demands exceed cognitive resources (Sweller, 2011). Each technological upgrade—whether a software change or a new device—adds layers of decisions the brain must process:

- learning new menus

- adjusting to new icons

- understanding new settings

- replacing previous automatic behaviors

When these changes occur frequently, cognitive overload becomes chronic, contributing to fatigue, irritation, and a sense of mental clutter.

The Psychological Burden of Planned

Planned obsolescence, the practice of designing products with limited future usefulness, affects not only consumers’ wallets but also their psychological wellbeing. Devices that slow down, stop supporting updates, or become incompatible with accessories force users into cycles of replacement.

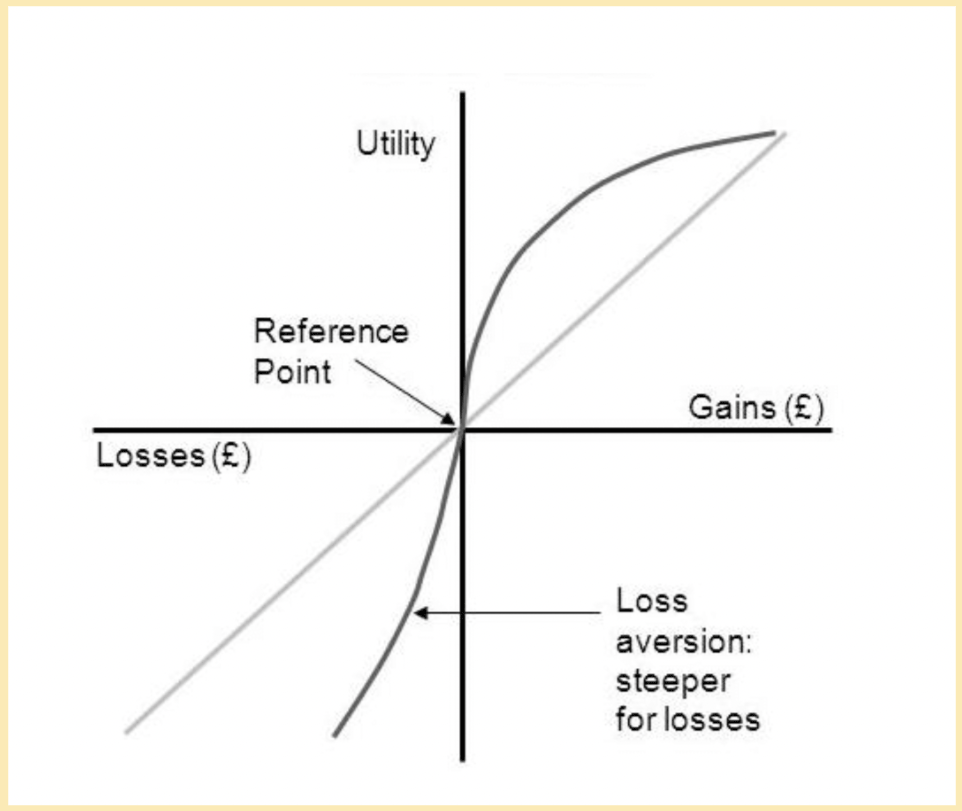

Loss aversion and emotional attachment to devices

Behavioral economics suggests that humans experience loss more intensely than gains (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). When a familiar device becomes obsolete, users experience a form of technological loss: the disappearance of a tool that has been integrated into daily routines. This loss triggers emotional resistance, anxiety, or resentment, which may contribute to future fatigue.

Decision fatigue and replacement pressure

Choosing a new device requires researching features, comparing models, navigating marketing jargon, and predicting future technological trends. Decision fatigue—a reduction in decision-making quality after extended periods of choice-making—becomes a central part of the tech upgrade cycle (Vohs et al., 2008). Over time, repeated device-related decisions contribute to psychological exhaustion.

Digital Transitions and Identity Pressure

Technological identities—how individuals see themselves in relation to technology—are increasingly shaping social perception. Being “tech-savvy” is often associated with competence, intelligence, and modernity. Conversely, struggling with upgrades can evoke feelings of inadequacy or embarrassment.

Studies show that individuals who feel less technologically proficient often experience self-doubt, social anxiety, and fear of judgment (Selwyn, 2004). Upgrades amplify this by constantly resetting the learning curve. Even proficient users can feel technologically inept when confronted with radically redesigned interfaces.

Organizations often adopt new technologies to signal forward-thinking status. However, employees may experience anxiety when forced to adapt quickly or when training is insufficient. Workplace studies on technology-induced stress (“technostress”) reveal correlations between rapid tech adoption and burnout, reduced job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion (Ayyagari et al., 2011).

Infinite Updates and the Erosion of Control

Psychologists agree that a sense of control is essential for mental wellbeing. When updates occur automatically—sometimes without user consent—they produce micro-disruptions in predictability and autonomy.

Each update requires attention, breaks workflow, or changes established processes. Research on attention fragmentation suggests that such interruptions reduce deep focus and contribute to mental fatigue (Mark et al., 2014). Over time, fragmented attention becomes a default cognitive mode.

When users repeatedly experience changes they cannot control or fully understand, they may develop a form of learned helplessness—a psychological state where individuals feel powerless to influence outcomes (Seligman, 1975). Frequent, unexpected updates can make people disengage from technology or experience chronic frustration.

Social Comparison and Tech-Driven Status

Social media amplifies upgrade culture by showcasing the newest gadgets and features. This leads to a digital form of status anxiety. Research shows that visible consumption influences self-esteem and comparative thinking (Dittmar, 2008). Seeing others adopt new technologies faster can trigger feelings of inadequacy or pressure to keep up.

Beyond individual psychology, future fatigue reflects broader cultural dynamics:

- accelerated capitalism

- attention economies

- media hype cycles

- innovation narratives

- the myth of constant optimization

Sociologists argue that modern societies equate progress with speed, creating an environment where slowing down feels irresponsible (Rosa, 2013). This cultural expectation undermines psychological rest.

Coping Strategies and Adaptive Mindsets

Some strategies to cope include:

1. Digital minimalism and intentional tech cycles

Intentionally delaying upgrades, simplifying digital ecosystems, and maintaining familiar tools can reduce cognitive load. Studies on digital minimalism show improvements in attention and wellbeing (Newport, 2019).

2. Building technological self-efficacy

Training, guided learning, and incremental exposure strengthen confidence and resilience in adapting to new systems.

3. Mindfulness and attention restoration

Mindfulness practices help counteract digital overstimulation, reducing stress and improving cognitive clarity (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Nature exposure and screen breaks also restore attention.

Conclusion

Future fatigue is a growing psychological phenomenon driven by the rapid pace of technological innovation. The human brain, shaped by evolution for steady, predictable change, struggles to keep up with constant upgrades, leading to cognitive overload, emotional exhaustion, and identity stress. Planned obsolescence, decision fatigue, and cultural pressure to remain technologically current intensify the burden. Understanding the mechanisms behind future fatigue allows individuals and institutions to adopt healthier strategies for managing technological transitions. As society continues racing toward increasingly complex digital futures, recognizing and addressing the psychological costs will be essential for maintaining human wellbeing in a rapidly evolving world.

References

Ayyagari, R., Grover, V., & Purvis, R. (2011). Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 831–858.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tierney, J. (2011). Willpower: Rediscovering the greatest human strength. Penguin.

Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646–664.

Dittmar, H. (2008). Consumer culture, identity and well-being. Psychology Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2014). The cost of interrupted work. CHI Conference Proceedings, 107–110.

Newport, C. (2019). Digital minimalism. Portfolio.

Rosa, H. (2013). Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity. Columbia University Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. Freeman.

Selwyn, N. (2004). Reconsidering political and popular understandings of the digital divide. New Media & Society, 6(3), 341–362.

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 55, 37–76.

Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., et al. (2008). Decision fatigue. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 883–898.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 12). Future Fatigue and 3 Important Ways to Cope With It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/future-fatigue/