Hope is often treated as a vague emotion—something soft, sentimental, and passive. People talk about having hope, feeling hopeful, or losing hope, as if it were an inexplicable feeling that either appears or disappears on its own. But psychologist Charles R. Snyder challenged this idea by developing a powerful, research-backed theory that treats hope not as emotion, but as a cognitive process—a way of thinking that fuels motivation, resilience, and goal achievement. His model, widely known as Hope Theory, has become one of the most impactful psychological frameworks for understanding human motivation.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Redefining Hope

Before Snyder’s work, hope was largely considered an emotional or spiritual concept. People saw it as a feeling, similar to optimism, or a moral virtue rooted in faith or belief. Snyder, however, argued that hope is a thinking process involving goal-directed behavior. In his view, hope could be measured, improved, and taught.

According to Snyder (1994), hope consists of two key cognitive components:

- Agency – the sense of determination and belief that one can achieve their goals (“I can do this”).

- Pathways – the ability to generate workable strategies to reach goals (“I can find a way”).

Hope, in this model, is not simply wishing. It is structured, intentional, and actionable. Instead of asking, “Do you feel hopeful?” Snyder might ask, “Do you believe you can create routes to your goals, and do you feel capable of following those routes?”

This shift changed the landscape of motivational psychology. It gave researchers and practitioners a blueprint for understanding why some individuals persevere while others quit, even when facing similar circumstances or levels of talent.

The Two Engines of Hope

Th two engines of hope include:

1. Agency

Agency refers to the sense of personal capacity, sometimes called willpower, self-determination, or goal-directed energy. Agency is the belief that:

- One’s actions matter

- Effort will produce results

- One has the internal power to act

Agency is deeply connected to self-efficacy, though the two are distinct. While self-efficacy refers to belief in one’s ability to perform specific tasks (Bandura, 1997), agency describes the broader motivational component that drives individuals toward desired outcomes.

People high in agency often think:

- “I can figure this out.”

- “I can keep going, even if it’s hard.”

- “My actions influence my future.”

Agency turns goals from fantasies into pursuits.

2. Pathways

Pathways thinking is the ability to:

- Imagine different ways to achieve a goal

- Problem-solve when barriers arise

- Generate backup strategies

Pathways thinking is closely related to creativity and cognitive flexibility. It requires individuals to shift perspectives, explore new methods, and adjust plans until they find viable solutions.

Consider two people facing the same obstacle. A high-pathways thinker might say: “Okay, this path didn’t work. What’s another route?”

A low-pathways thinker may say: “This didn’t work. I guess the goal isn’t possible.”

Hopeful individuals are distinguished not by luck or talent but by their ability to construct new routes and maintain belief in their ability to use them.

Hope as a Dynamic System

Agency and pathways work like two sides of a motivational engine.

- High agency + high pathways = strong hope

- Low agency + high pathways = “I know ways, but I don’t believe I can do them”

- High agency + low pathways = “I believe in myself, but I don’t know what to do”

- Low agency + low pathways = hopelessness

Hope is strongest when both components work together. It is not enough to believe you can reach a goal; you must also understand how to get there.

Snyder emphasized that hope is not a personality trait fixed at birth. Instead, it is learned and malleable, fluctuating based on experiences, environments, and cognitive habits.

Measuring Hope

One of Snyder’s most notable contributions is the development of the Hope Scale, a validated measurement tool assessing both agency and pathways thinking. Participants rate statements like:

- “I energetically pursue my goals.”

- “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam.”

- “I meet the goals that I set for myself.”

Research consistently shows that higher hope scores correlate with:

- Better academic performance

- Stronger psychological well-being

- Higher athletic performance

- Better coping during illness

- Greater resilience after trauma

The Hope Scale transformed hope from a philosophical concept into a measurable psychological construct.

Psychological and Behavioral Benefits

Some psychological benefits of it include:

- Motivation and Goal Achievement: High-hope individuals set more goals, pursue them more persistically, and adjust strategies more flexibly when obstacles appear. They interpret setbacks not as failures but as challenges requiring new pathways.

- Emotional Well-being: Research shows that hope predicts lower levels of: anxiety, depression, and burnout It also increases levels of: life satisfaction, positive emotions, and sense of purpose. Hope acts as a psychological buffer, helping individuals maintain emotional stability even during stress.

- Academic Success: Students with high hope show: higher GPA, better study habits, and greater likelihood of completing school. This occurs because they generate multiple pathways for academic success and believe they can follow them.

- Physical Health and Recovery: Individuals with high hope experience: faster recovery from surgeries, better disease management, and greater adherence to treatment plans

Hope is not magic—it’s cognitive. Patients who believe they can take steps toward recovery behave differently, make healthier decisions, and persist when treatments are difficult.

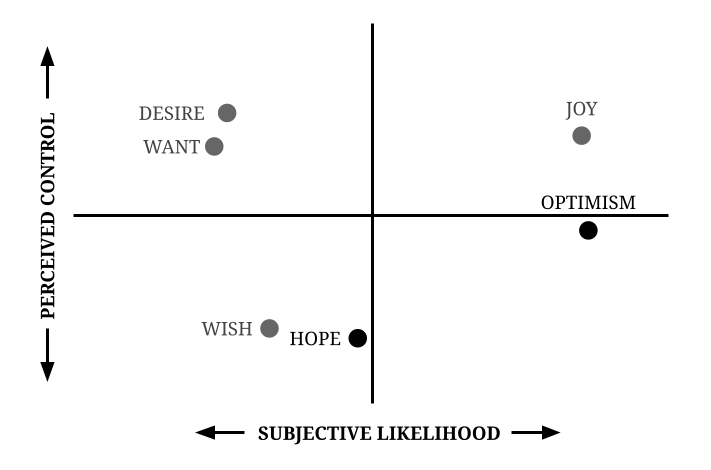

Hope vs. Optimism

Optimism is the belief that things will turn out well. Hope is the belief that you can make things turn out well. Optimism is passive; hope is active. Optimism is about expectations; hope is about agency and pathways. Both are useful, but hope is more tightly connected to goal achievement because it involves strategy and self-belief.

Cultivating Hope

Hope can be taught, strengthened, and practiced. Here are key techniques supported by research:

- Clarify and Set Specific Goals: Hope thrives on clear endpoints. Vague goals drain motivation because there’s no obvious route forward.

- Break Goals Into Pathways: List: the main route, backup routes, micro-steps, and alternative strategies. This builds pathways thinking.

- Strengthen Agency Through Self-Efficacy: Agency increases when individuals: celebrate small wins, track progress, reframe failures as problem-solving triggers, and recall past successes. Every completed step reinforces the belief that “I can do this.”

- Anticipate Barriers: Instead of being surprised by obstacles, hopeful individuals expect them and plan ahead. This reduces emotional shock and boosts cognitive resilience.

- Use Mental Contrasting: This technique involves imagining your goal and then acknowledging the obstacles. It trains the brain to pair agency and pathways automatically.

- Surround Yourself With High-Hope Individuals: Hope is contagious. Social environments shape beliefs about what is possible, and high-hope people naturally model effective goal pursuit.

Hope in Modern Life

In an era marked by burnout, uncertainty, rapid technological change, and social upheaval, hope is more than comforting—it is essential. People today often struggle with:

- Information overload

- Burnout

- Anxiety about the future

- Feeling stuck or directionless

- Lack of structure due to remote work

- Global instability

Hope Theory provides a toolkit for navigating these challenges. It teaches people to strategically approach life’s difficulties, instead of waiting for circumstances or feelings to improve.

Leaders use hope to motivate teams. Teachers use it to guide students. Counselors use it to support clients. Individuals use it for personal growth. Hope Theory is deeply human yet cognitively precise—a rare combination that has allowed it to thrive for more than three decades.

Critiques and Limitations of Hope Theory

While widely influential, Hope Theory has limitations.

- Cultural Differences: Some researchers argue that agency, as defined by Snyder, is very Western. In collectivist cultures, agency may be rooted in group success, not personal willpower. Nonetheless, pathways thinking appears to be universal.

- Overemphasis on Cognition: Critics suggest that focusing purely on cognitive mechanisms underestimates the emotional and unconscious processes in motivation.

- Goal-Dependence: Hope Theory works best with clear, structured goals. It is less useful for individuals who feel aimless or disoriented—though developing goals is itself part of hope-building.

Despite these critiques, the theory remains one of the most widely supported models of motivation and resilience.

Conclusion

Charles Snyder transformed hope from a poetic abstraction into a psychological roadmap. His work shows that hope is not a gift granted to the lucky, nor a feeling that comes and goes at random. It is a thinking style, a cognitive strength, and a trainable skill that allows individuals to create pathways toward their goals and believe in their ability to walk them.

In a world filled with uncertainty, hope is not wishful thinking—it is strategic, intentional, and empowering. When agency and pathways unite, hope becomes an engine capable of driving meaningful change in individuals, communities, and society.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. Free Press.

Snyder, C. R., Cheavens, J., & Sympson, S. (1997). Hope: An individual motive for social commerce. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 1(2), 107–118.

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820–826.

Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., & Sigmon, D. R. (2002). Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 257–276). Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 9). Understanding Hope Theory and 3 Important Components of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/understanding-hope-theory/