Introduction

Every day, individuals make countless decisions—some trivial, some strategically significant. Yet these decisions are rarely as rational or objective as we like to believe. Cognitive biases, systematic patterns of deviation from rational judgment, subtly influence how we interpret information, evaluate risks, and choose actions. While biases serve as mental shortcuts that allow the brain to conserve energy, they also lead to flawed reasoning and costly errors. In workplaces, cognitive biases can shape hiring processes, negotiations, leadership choices, team dynamics, and strategic planning.

Read More: Ragebait

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases emerge from the brain’s attempts to simplify complex information (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Rather than processing all available data, people rely on heuristics—efficient mental shortcuts that allow for quick judgments. While heuristics are often useful, they can produce predictable distortions.

In the workplace, these distortions matter. Leaders make decisions under uncertainty, employees interpret ambiguous situations, and teams constantly balance competing demands. Biases can lead to overconfidence, conflict, miscommunication, and suboptimal choices. Understanding them is essential for improving organizational performance.

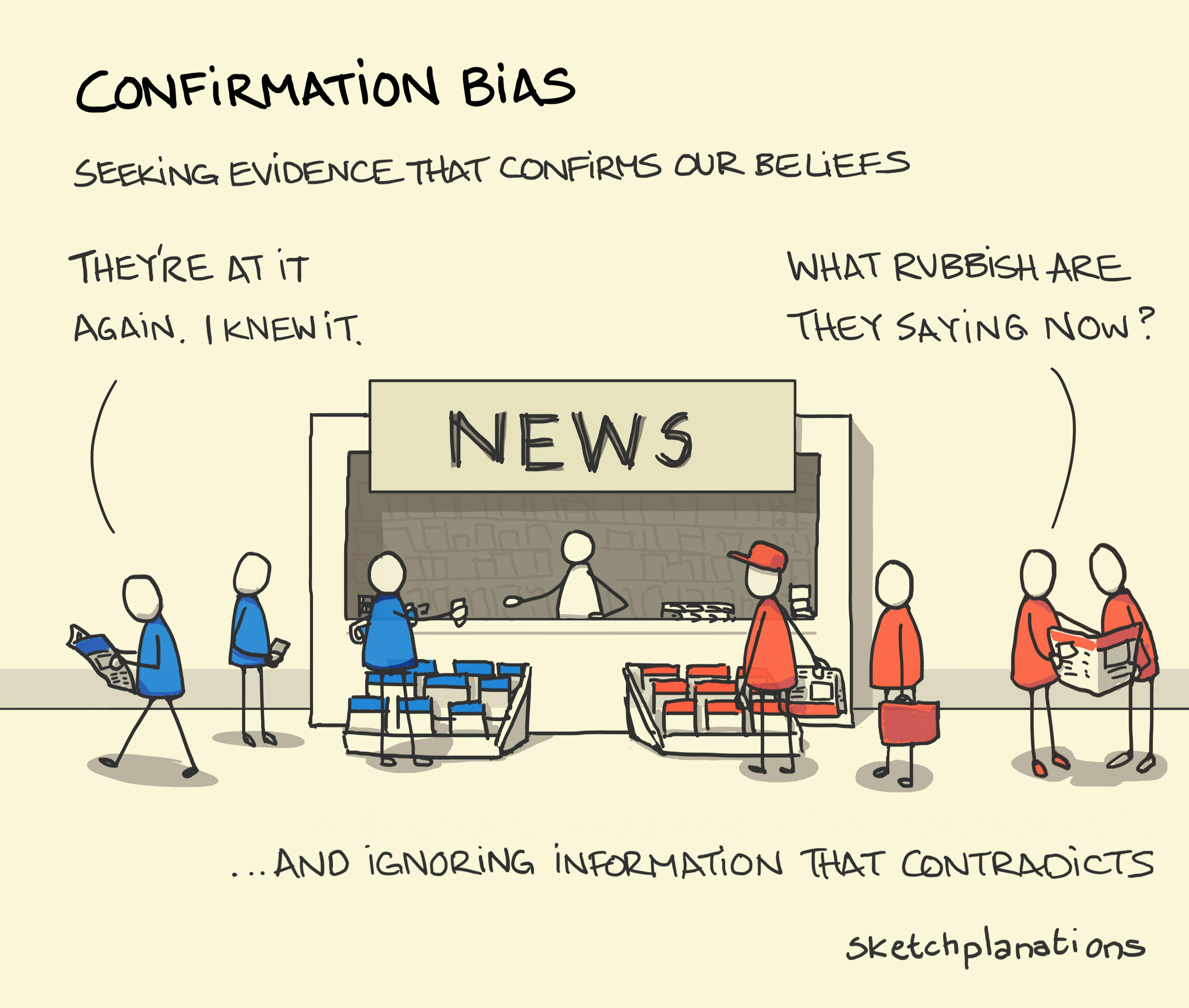

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias refers to the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in ways that confirm existing beliefs (Nickerson, 1998). Rather than evaluating evidence objectively, people give more weight to information that aligns with their expectations.

How Confirmation Bias Shows Up at Work

- Hiring and Performance Evaluations: Managers may form early impressions of a job candidate and unconsciously seek information that supports their initial judgment. This can cause interviewers to ask leading questions or overlook contradictory evidence (Gilbert, 1991). Similarly, performance evaluations may be skewed by preconceived notions about an employee’s competence.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Leaders may prioritize data that supports their preferred strategies while discounting risks or warnings. This can lead to escalation of commitment—continuing a failing project due to selective interpretation of information (Staw, 1981).

- Team Dynamics: Teams may experience groupthink when members seek agreement over accuracy (Janis, 1982). Confirmation bias reinforces consensus at the expense of dissenting but valuable viewpoints.

Why Confirmation Bias Persists

The bias is driven by several psychological forces:

- Cognitive ease: It is mentally easier to process information that aligns with existing beliefs.

- Emotional comfort: Beliefs are tied to identity, so contradictory information may feel threatening.

- Social reinforcement: In workplace cultures that reward harmony over critical thinking, validation is more valued than accuracy.

Confirmation bias can impair judgment and stifle innovation. Organizations may fail to adapt to market changes or miss emerging risks. Managers may misjudge employees, perpetuating inequity and limiting talent development.

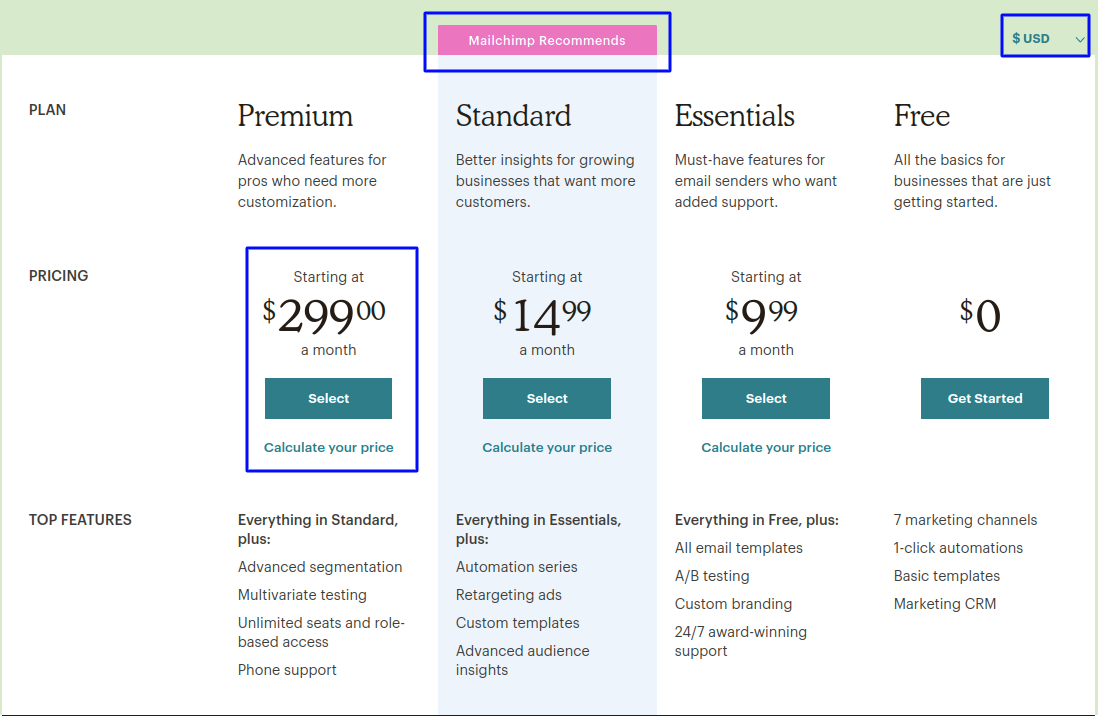

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring occurs when individuals rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive—the “anchor”—when making decisions (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Even irrelevant or arbitrary numbers can have a powerful effect on judgments.

Anchoring in Workplace Contexts

- Salary Negotiations: The first number mentioned in a negotiation heavily influences the final outcome. Candidates who anchor high often receive higher offers, while those who anchor low set expectations that may limit their earning potential (Galinsky & Mussweiler, 2001).

- Budgeting and Forecasting: Initial estimates shape subsequent projections, even when new data emerges. This can result in overly optimistic sales forecasts or misaligned resource allocation.

- Project Planning: Anchoring affects judgments of timelines and costs. Initial project estimates often become fixed points, causing teams to underestimate risks or fail to adjust plans when circumstances change.

Anchoring persists because the brain uses the anchor as a reference point and adjusts insufficiently from it. Under cognitive load or time pressure—common conditions at work—anchoring becomes even more influential (Epley & Gilovich, 2006).

Anchoring can lead to poor financial decisions, negotiation disadvantages, and unrealistic project expectations. Organizations that ignore anchoring may experience budget overruns, delayed releases, and mispriced contracts.

How Biases Interact in Workplace Decisions

Confirmation bias and anchoring often work together. For instance, once an anchor is set, confirmation bias leads individuals to look for information that supports the anchored value. This creates a feedback loop that reinforces initial impressions, regardless of accuracy.

Consider a hiring scenario:

A recruiter sees one early positive trait in a candidate (anchor). During the interview, they then selectively attend to supportive cues (confirmation bias). The end result is a biased evaluation that may not reflect actual job fit.

Similarly, leaders who set early strategic goals may cling to them even when evidence shifts—a combination of anchoring, confirmation bias, and escalation of commitment.

Mitigating Cognitive Biases at Work

While biases are inherent to human cognition, organizations can implement strategies to reduce their negative impact.

1. Structured Decision-Making Processes

Standardizing evaluations helps reduce subjective interpretation. Structured interviews, for example, have been shown to lower confirmation bias and improve hiring accuracy (Campion, Palmer, & Campion, 1997).

2. Encouraging Dissent and Critical Inquiry

Psychological safety—an environment where employees feel comfortable challenging assumptions—helps counter groupthink and confirmation bias (Edmondson, 1999). Leaders should actively solicit alternative viewpoints.

3. Pre-Mortem and Red-Team Exercises

Imagining how a decision could fail (pre-mortem analysis) exposes blind spots. Red-team strategies introduce deliberate opposition to test assumptions.

4. Independent Data Checks

Having separate teams verify data reduces the risk that biased interpretations will go unchallenged. This is especially valuable in forecasting or financial planning.

5. Delaying Judgment

For anchoring, delaying exposure to initial numbers or considering multiple starting points can reduce bias. Negotiators are trained to research market rates before hearing an offer, thereby reducing reliance on the anchor.

6. Bias Awareness Training

While awareness alone does not eliminate bias, it increases vigilance and encourages the adoption of debiasing strategies (Morewedge et al., 2015).

7. Data-Driven Cultures

Organizations that emphasize evidence-based reasoning create systems where decisions rely on validated data rather than intuition. However, this requires a culture of transparency and accountability.

Conclusion

Cognitive biases such as confirmation bias and anchoring are powerful forces shaping everyday workplace decisions. Although they originate as mental shortcuts that simplify complex information, they can distort hiring practices, negotiations, leadership choices, team dynamics, and strategic planning. By recognizing these biases and implementing structured debiasing strategies, organizations can make more accurate decisions, reduce errors, and foster environments where innovation and critical thinking thrive. The first step toward better decision-making is acknowledging that even the most confident judgments may be influenced by hidden cognitive forces.

References

Campion, M. A., Palmer, D. K., & Campion, J. E. (1997). Structured interviews and bias reduction.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams.

Epley, N., & Gilovich, T. (2006). The anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic.

Galinsky, A. D., & Mussweiler, T. (2001). Anchoring in negotiations.

Gilbert, D. T. (1991). How mental systems believe.

Janis, I. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions.

Morewedge, C. K., et al. (2015). Debiasing decisions.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon.

Staw, B. M. (1981). Escalation of commitment.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 8). Cognitive Biases at Work and 7 Important Ways to Mitigate Them. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/cognitive-biases-at-work/

Pingback: 7 First Impression Tips to Make a Lasting Impact - PsychUniverse